In our latest podcast episode, you will hear about great stories of danger, sacrifice and bravery. Here is one about saving not lives nor democracy but monuments, fine arts and archives.

The Monuments, Fine Arts and Archives Section

You may have heard of, or seen, George Clooney’s ‘The Monuments Men’ film. It took much artistic licence. There were 345 Monuments Men (and women!) who, as part of the Monuments, Fine Arts and Archives (MFAA) Section, protected and researched monuments and other cultural ‘treasures’ during the Second World War and in its immediate aftermath.

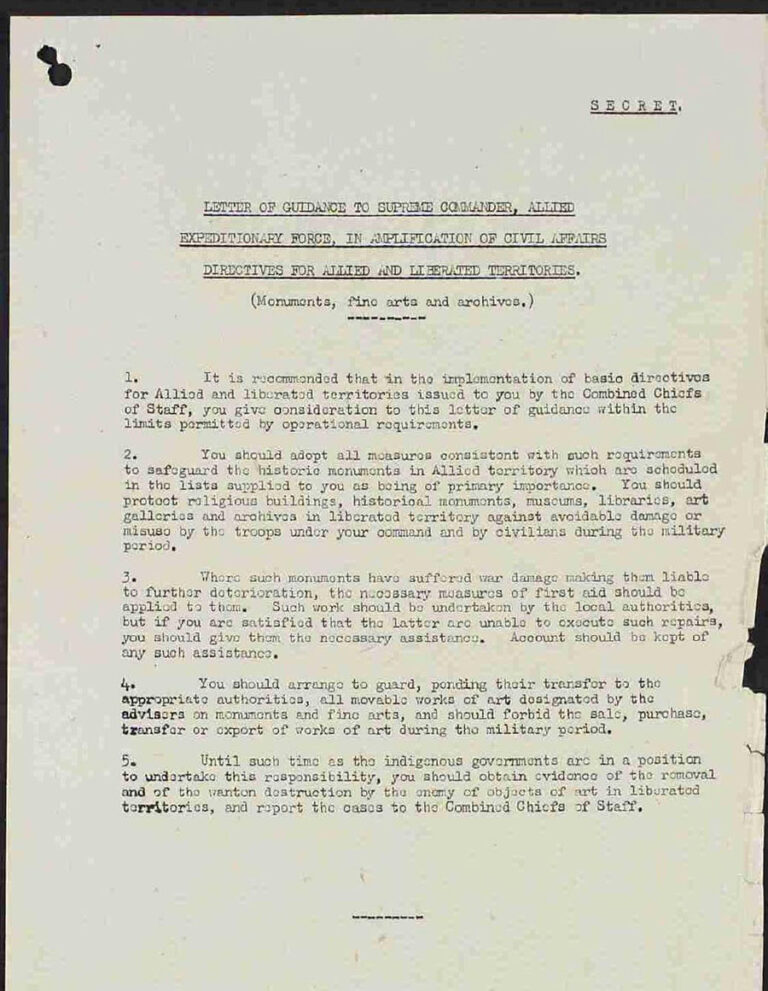

The MFAA was created in 1943 to ‘protect religious buildings, historical monuments, museums, libraries, art galleries and archives in liberated territory’, when the American president, Roosevelt, authorised the formation of the American Commission for the Protection and Salvage of Artistic and Historic Monuments in War Areas’ (FO 371/40683/12).

The Foreign Office commented at the time that ‘the most useful function of the U.S. commission would lie in educating U.S. Army Officers to appreciate that steps must be taken to prevent wilful damage and “souvenir hunting” in museums and ancient buildings in the operational zone’ (FO 371/35451/4).

This was largely unfair, and not in the least representative of the enormous amount of work the MFAA would accomplish.

Here at The National Archives, we have our very own Monuments Men – Hilary Jenkinson, Humphrey Brooke, Roger Ellis and Harry Bell, who had all worked together at the Public Record Office (PRO) before the war.

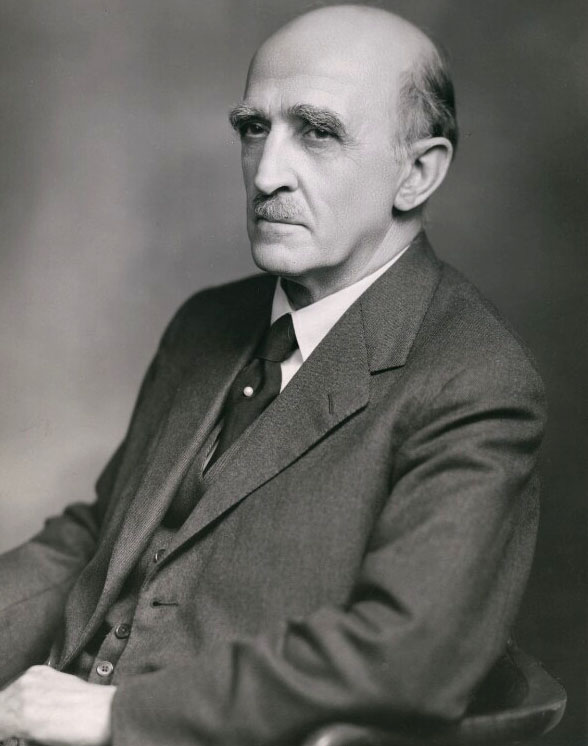

Hilary Jenkinson and the Italian Archives

In 1943 Hilary Jenkinson, a Principal Assistant Keeper at the PRO, was asked to advise the War Office on matters relating to the protection of archives in occupied territories.

Jenkinson arrived in Italy at the beginning of 1944 and, during this first tour of archives, visited some 70 repositories in the country. He was rather dismayed by the condition of the records. He wrote:

‘A building had been damaged and nothing had been done (…); the Archivist had disappeared and no one had taken his place; some thousands of volumes had become wet and no steps had been taken to dry them; and so forth’ (T 209/10).

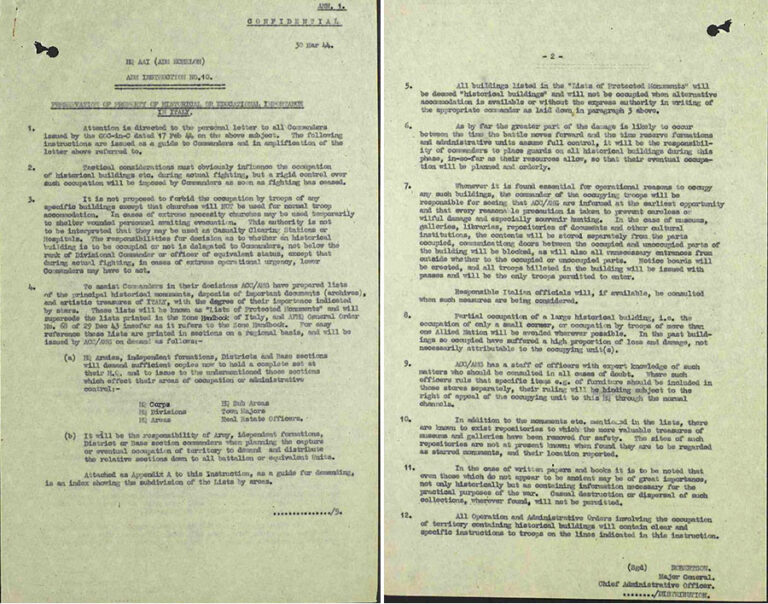

He had arrived in Naples just in time to (forcefully) suggest what would become paragraph 11 of the Allied Army in Italy Administrative Instruction No 10:

‘In the case of written papers and books, it is to be noted that even those which do not appear to be ancient may be of great importance, not only historically but as containing information necessary for the practical purposes of the war. Casual destruction or dispersal of such collections, wherever found, will not be permitted.’

From then on, Jenkinson would keep insisting on ‘the special danger to which archives are subject’, which came from dispersal as well as destruction. As the Italian Campaign was still raging, archives needed to be protected from Allied bombing, of course, but also from occupying troops, civilians and ‘the indiscreet use of Modern Archives by Intelligence Officers and others’ (T 209/10).

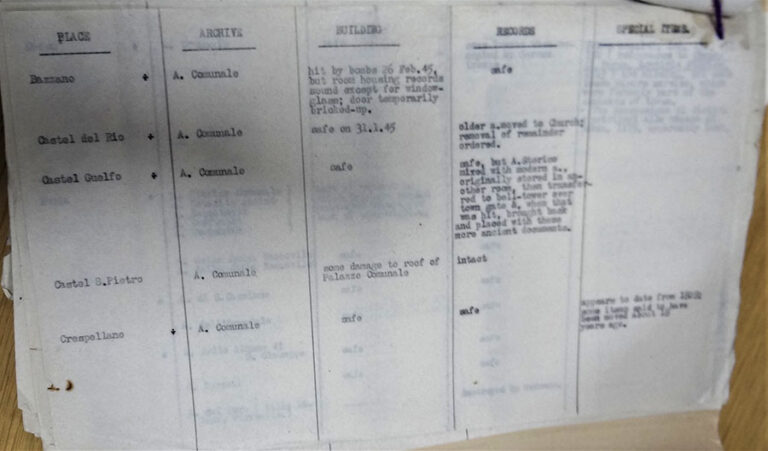

His first task was to draw up a comprehensive list of Italian archives, a never-ending task, which continued well after the armistice. The collections were examined, of course, but also the buildings and the archivists themselves.

Archives, Jenkinson warned, ‘are not necessarily old or beautiful, though they often may be’. ‘Whether they date from (…) early periods or from the present day (…),’ he continued, ‘all are in some sense unique and therefore irreplaceable’ (PRO 30/75/43).

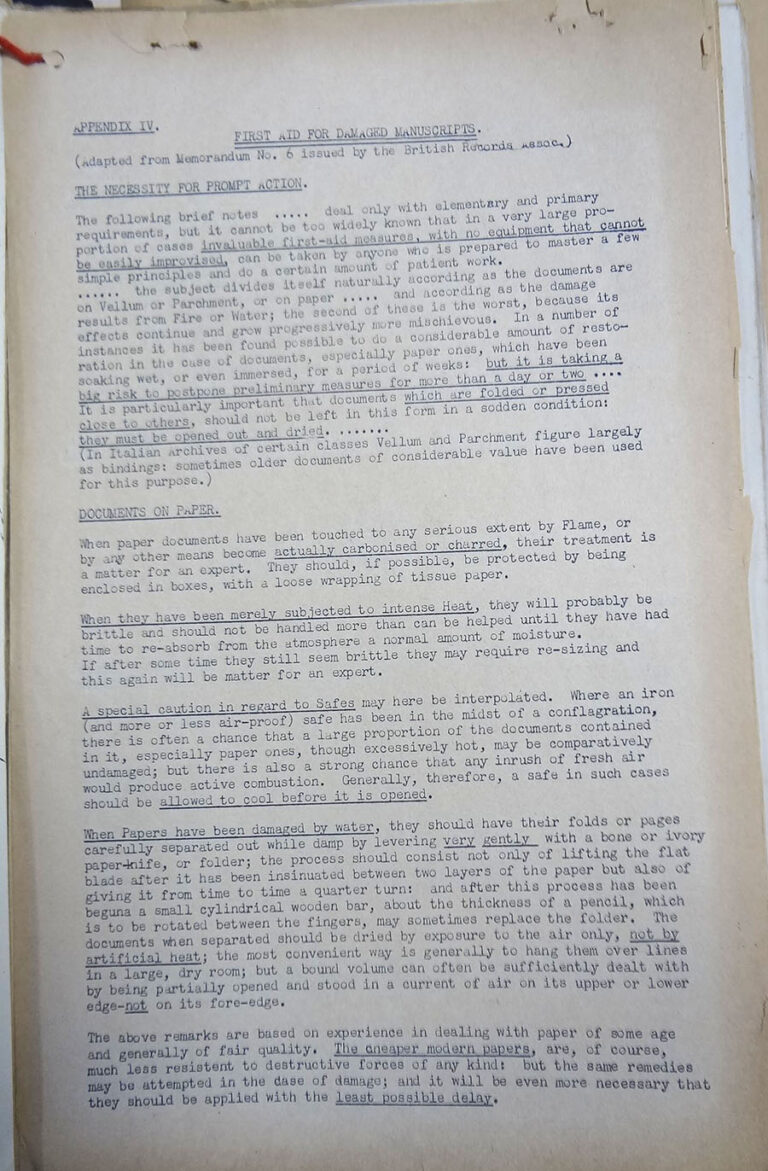

Archives, he said, were fragile and endangered by the fact that people generally didn’t know what they were or what purpose they could serve. If documents were found damaged, they should be given first aid – which could usually be done with improvised equipment sourced locally.

Jenkinson also put together a paper on the ‘Duties of Archivists’ – visit as many repositories as possible, collaborate as closely as possible with the Italian Archives Authorities; continue to liaise with Intelligence and ensure the safeguarding of modern records. This last point was particularly important as it wasn’t only an issue of preserving records of historical value, but also look for information which could be useful in the course of the war.

‘Officers of various agencies’ were foraging for intelligence and removing files or papers with very little deference to basic archival principles. Jenkinson complained: ‘by doing so they not only impair the historical value the collection as a whole may have, but also impede or make impossible the work of other agencies’ (T 209/10). Besides, many different people were handling sometimes fragile documents, probably without the necessary care.

The safeguarding of Modern Records was not part of the MFAA’s remit, but Jenkinson viewed them as just as important as the ancient or historical archives. The captured archives were used for intelligence purposes, and the greatest challenge was to make those in charge of extracting valuable information understand archival principles and the administrative history of these documents. They were not random documents, Jenkinson insisted, they were continuous series of documents. Disrupting the series would be a disaster.

Incidentally, Jenkinson also took advantage of his time in Italy to suggest a better system for the records of the Allied Control Commission itself. By the time he left, the AAC had an Archives Department.

Jenkinson made it back to Britain in the summer of 1944, leaving the protection of the Italian Archives in the hands of trusted colleagues: Brooke, Ellis and Bell. He would continue to monitor the situation in Italy and to make occasional visits to the country, but he turned his attention to Germany and modern records there.

‘Many adventures’

Jenkinson’s papers in PRO 30/75 contain many letters from Brooke, Ellis, and Bell, who continued his work in Italy. Some of them conjure up images that would give any PRO staff nightmares. Ellis, for instance, described how, during a repository visit, he found ‘an immense heap of white dust with no documents visible at all’. The task was herculean but, Ellis wrote, ‘this is the greatest fun and I have had many adventures already’ (PRO 30/75/42).

Yet the work was relentless and the territory to cover incredibly vast for such a small number of officers.

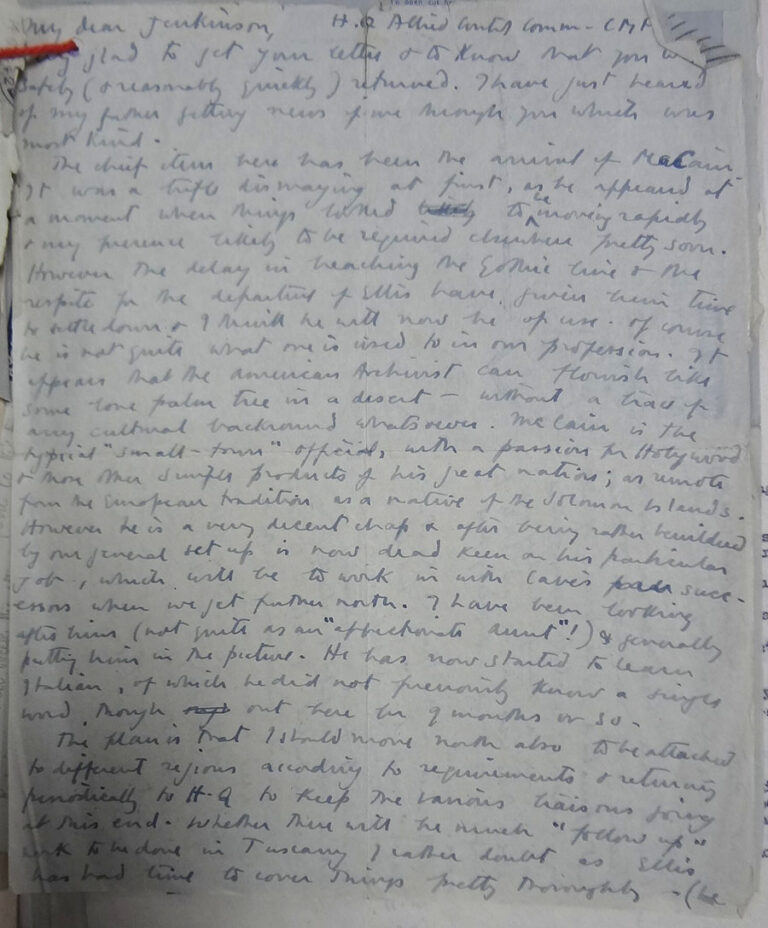

Our British archivists were sent reinforcement from America. The first American archivist to arrive in Italy was William McCain, and Brooke and Ellis were not impressed. ‘Latin and French he once studies a bit at College’, Ellis lamented. Brooke was a bit more colourful in his letter and wrote:

‘He was a trifle dismaying at first (…). He is not quite what one is used to in our profession. It appears that the American Archivist can flourish like some lone palm tree in the desert – without a trace of cultural background whatsoever.’

He was, he continued, ‘as remote from the European tradition as a native of the Solomon Islands’ but ‘a very decent chap’.

Together, and thanks to Jenkinson’s previous work and continuous guidance, as well as that of the Director of the Roosevelt Library in the United States, Fred Shipman, they followed in the footsteps of the 8th Army, planning archival visits depending on which city might fall first.

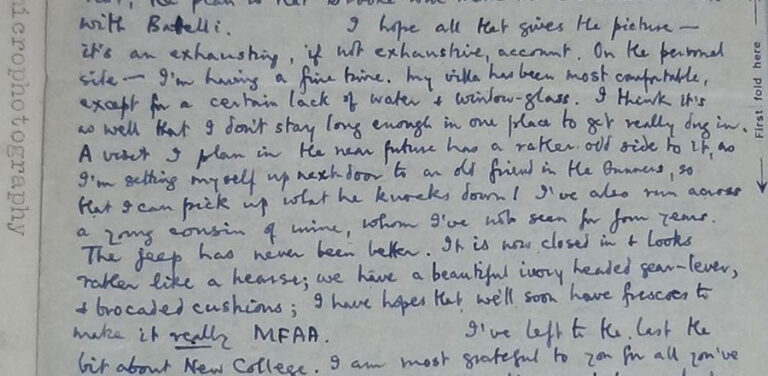

Bell wrote flippantly about having to hold his breath to squeeze through a hole and down a 20-feet ladder to inspect sodden records, and described his accommodation and jeep in the most humorous way. ‘It’s a great life!’ he wrote. But they were very close to the front. Having covered about 8,000 kilometres in the first five months of 1945, Bell entered Bologna on the very day on which it was liberated. They were advancing with the allied forces so that they could ‘pick up what [they knocked] down’.

It was dangerous work.

In his report on The Protection of Archives in Italy, Jenkinson wrote:

‘Many people must have wondered with a pang, when the fighting reached Sicily, what would happen to the more famous Italian Archives – to the records of the Medici at Florence or the Norman Kings in Naples and Palermo.’

Thanks to Jenkinson and his colleagues, working around the clock to protect the archives in immediate danger of destruction or dispersal, and to ‘restore to working order the Italian system of archive administration’, these records are mostly safe (FO 1050/1432).

In May 1944, General Wilson, Supreme Commander, Allied Forces Mediterranean Commander, wrote the foreword to a pamphlet on the preservation of works of Art in Italy. He was quite clear:

‘In war great damage to buildings, including churches and those of great historical value, has to be accepted when it is operationally unavoidable. To add to such destruction either by wanton action or through thoughtlessness is a crime against civilization’ (T 209/10).

The role Jenkinson, Brooke, Ellis, and Bell played in the preservation of the European cultural heritage, and in the understanding of contemporary events, was absolutely vital. These men were archival heroes.

On the Record: series four available now

In our latest three-part podcast series we explore stories in our collection with the theme of heroic deeds. In the episodes you’ll hear about spies parachuting into enemy territories and knights slaying dragons. You’ll also hear about health inspectors trying to improve the living conditions of poor Londoners, and leaders using their skills to organise for change.

Subscribe: iTunes | Spotify | RadioPublic | Google Podcasts

You can also catch up on previous series in which we have uncovered the true stories of famous spies and looked at protest – from the medieval Peasants’ Revolt to Black power in the courtroom. Most recently we have marked the 80th anniversary of the Battle of Britain and Refugee Week by delving into lesser-known personal stories from our collection.

I agree that what Jenkinson et al did was the right thing at a very dangerous time. We should never let documents disappear as they tell history, warts and all.