‘Perestroika’ and ‘glasnost’. These are two Russian words you may have heard at school when struggling through the USSR chapter of your history books. Thirty years ago, on 11 March 1985, the man who was to coin them, Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev, became the youngest man to take over as General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. The youngest, and the last.

Most of us know Mikhail Gorbachev as the man who initiated the process which culminated in the collapse of the Soviet Union, the reunification of Germany and the end of the Cold War. When he came to the UK for an official visit in 1984, however, Gorbachev was only the rising star of the Politburo – or, as the Times put it on 13 December 1984, ‘the golden boy of Soviet Politics.’

The aim of the visit was to ‘develop the dialogue between the two countries, extend mutual understanding and find points of contact and convergence on important issues’. For Charles Powell, the Private Secretary, it was ‘a unique opportunity to try to get inside the minds of the next generation of Soviet leaders.’

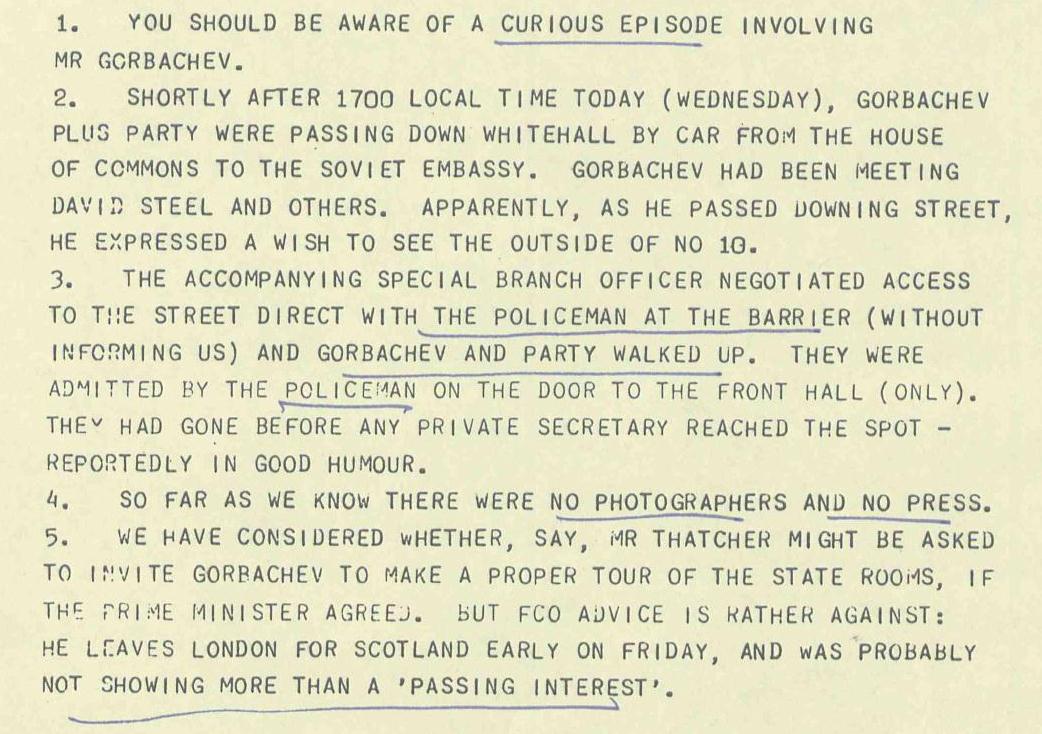

According to the British Ambassador in Moscow, Gorbachev wanted ‘frank political discussions with the Prime Minister, with no diplomatic formalities, on the current world situation.’ He displayed very little formality indeed when he dropped by Number 10 quite unannounced…

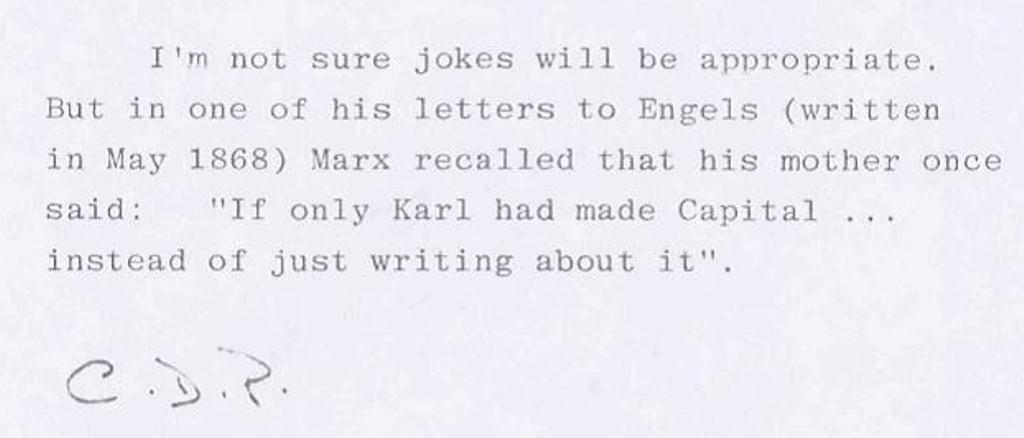

Mr Gorbachev and Mrs Thatcher were to have lunch at Chequers. This was carefully prepared, down to the jokes the Prime Minister might want to include in her speech: ‘I’m not sure jokes will be appropriate,’ Powell, wrote the day before, ‘but in one of his letters to Engels (written in May 1868) Marx recalled that his mother once said: “if only Karl had made Capital… Instead of just writing about it”‘.

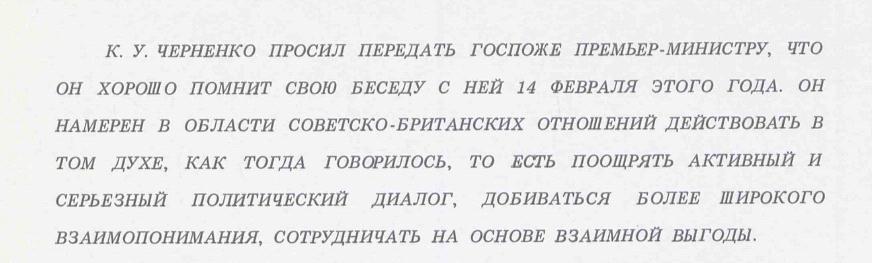

Over lunch, and during the meeting which followed, Gorbachev and Thatcher discussed a number of issues, notably general mutual perceptions, East/West relations, mutual perceptions of security, nuclear weapons, economic and social themes, the miners’ strike, human rights… Gorbachev also delivered a message from Konstantin Ustinovich Chernenko, the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, whom Margaret Thatcher had met in Moscow when she had attended Andropov’s funeral in February 1984. The Soviet leader expressed his wish to ‘promote an active and serious political dialogue, to strive for a wider mutual understanding,’ and ‘to cooperate on the basis of mutual benefit.’

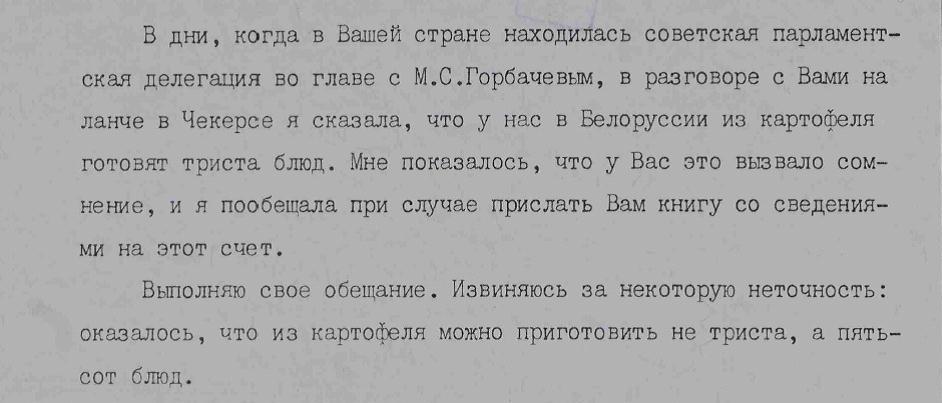

Meanwhile, Gorbachev’s wife, Raisa Gorbacheva, seems to have been discussing potatoes with the Minister of Agriculture, Michael Jopling. On 19 July 1985, she sent him a book, reminding him of their conversation. ‘I told you at the luncheon at Chequers that in Belorussia we have three hundred recipes to cook potatoes,’ she wrote. ‘It seemed to me that you were doubtful about it and I promised to send you a book containing information in this regard at a later date. I am keeping my promise. My apologies for being somewhat inaccurate: in fact, there are five hundred rather than three hundred, recipes to cook potatoes.’

During this visit, which Margaret Thatcher later described as ‘an outstanding international success,’ Gorbachev appeared to be a rather atypical Soviet official who nevertheless remained loyal to the system.

A Foreign Office memo of 4 December 1984 describes Gorbachev as part of a ‘new generation’ of Soviet leaders. He had not been born when Lenin died, he hadn’t held any position under Stalin, and the first Party Congress he attended as a Komsomol delegate was the 20th, in 1956, during which Khrushchev denounced Stalin in his famous ‘secret speech’.

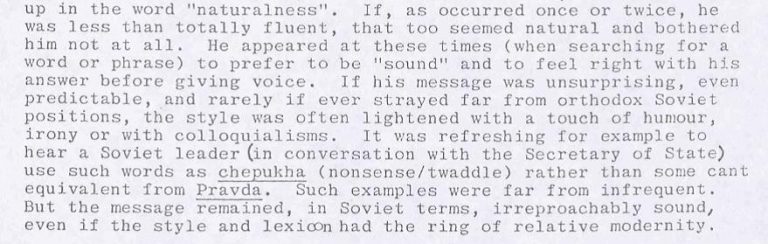

The British Ambassador in Moscow stressed, before the visit, that Gorbachev was ‘more open in manner than the traditionally stony-faced Soviet leadership and his youth and vigour make a refreshing change from the ageing and sick figures of recent years.’ It seems that Gorbachev distanced himself from the rigid Soviet ideological discourse the Westerners had been used to. His interpreter thought his ‘style was often lightened with a touch of humour, irony or with colloquialisms. It was refreshing for example to hear a Soviet leader (…) use such words as chepukha (nonsense/twaddle) rather than some cant equivalent from Pravda.’

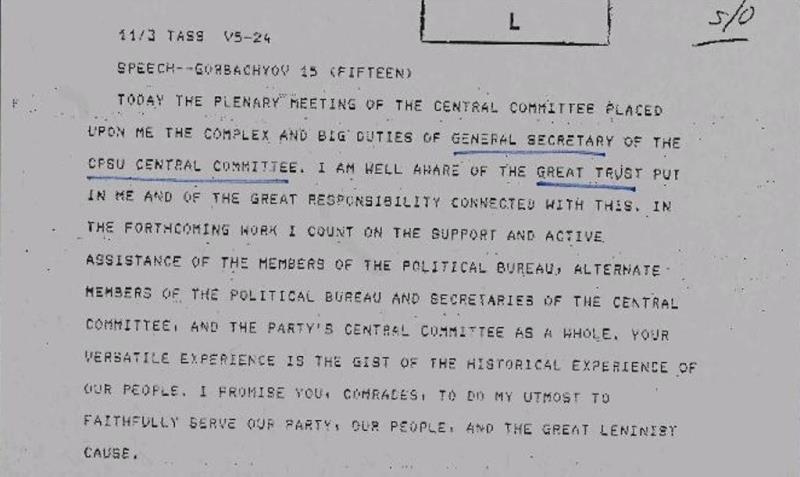

However modern Gorbachev sounded, he was still very much a product of the Soviet system and had spent very little time out of it. Just before the London visit, Gorbachev had delivered a major domestic speech on contemporary Soviet ideology. His watchword was continuity rather than change. Therefore, when Gorbachev was elected as General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union on 11 March 1985, following Chernenko’s death, his speech at the plenary meeting of the CPSU central committee, reaffirming the bases of Soviet ideology, came as no surprise. ‘The strategic line worked out at the 26th Congress and at the subsequent plenary meeting of the Central Committee with vigorous participation of Yuri Vladimirovich Andropov and Konstantin Ustinovich Chernenko, has been and remains unchanged,’ he said.

Extract from Gorbachev’s speech the plenary meeting of the CPSU central committee, 11/03/1985. Catalogue reference PREM 19/1646.

All the subjects covered by this speech (economic policy, foreign policy, nuclear weapons…) showed continuity with the existing party line rather than a real generational shift. Gorbachev wanted to reform the system without getting rid of it. The very terms of ‘perestroika’ (‘restructuring’, as in restructuring the political and economic system), ‘demokratizatsiya’ (‘democratisation’, as in authorising multi-candidate elections), ‘uskoreniye’ (‘acceleration’, as in accelerating the social and economic development), and ‘glasnost’ (‘transparency’, as in achieving more transparency in government institutions and activities) remain in line with the ideological discourse. However, it certainly was a shift in thinking.

According to his interpreter during the 1984 visit, ‘the combination of cleverness, modern-mindedness, Slav nationalism, energy, charm, self-assurance and single-mindedness would make [Gorbachev] at worst a formidable adversary and at best an interlocutor to be treated with the utmost respect and circumspection.’ For Margaret Thatcher, who ‘rather liked him,’ he was ‘a man one could do business with.’

Gorbachev was previously in charge of ensuring the grain harvest was met and which at the time was regarded as one of the toughest jobs, the analysis by Brian Walden on the ‘Weekend at One’ I think it was, the best political programme there has been.

The ‘Foreign Office’ of course did not exist in 1984 (it had not since 1968), it was and is the Foreign and Commonwealth Office. It was interesting to see the suggestion that ‘Mr Thatcher’ invited him, but one wonders about the security at No 10 at the time.

Did not Winston Churchill argue for the continuance of the British Empire, both cogently and continuously, stating the he was not elected “to oversee the dissolution of the Empire” under his premiership?

Yet Peter Clarke’s book does more than suggest the ascendancy of the Americans was due to the terms of Lend-Lease, the aid that allowed Britain to survive by ensuring their economy both went 100% to war footing and production, while reducing their exports to near nil for the entire war.

Some might argue that the seeds of the British demise started under Edward VII, but certainly after the catastrophe of WWI did this sad fact come to full flower.

Gorbachev was a product of his political upbringing and culture, as was W.L.S.-C.

great development for documentary era