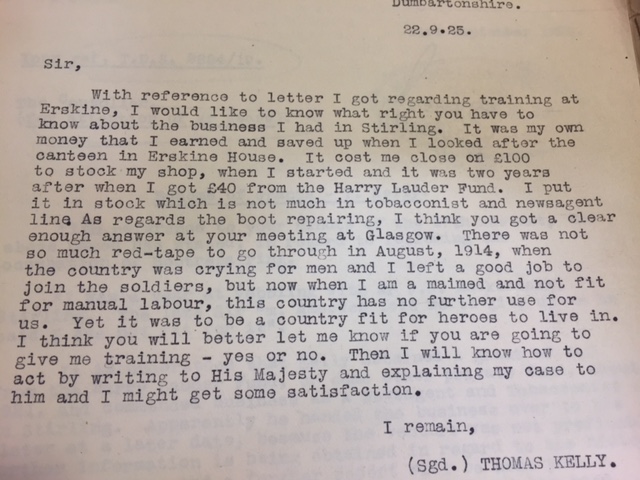

‘But now when I am a maimed and not fit for manual labour, this country has no further use for us.’

These are the words of a disgruntled ex-serviceman, Thomas Kelly, a private in the Gordon Highlanders, and a man who returned from the First World War in receipt of a 100% disability pension after having both of his legs amputated above the knee. These are the words of one ex-serviceman who returned from the war with a disability, but his situation was not an unfamiliar one. Nearly 6 million British and German men were disabled by injury or disease in the period 1914-1918 [ref]1. Deborah Cohen, The War Come Home: Disabled Veterans In Britain And Germany, 1914-1939 (California: University Of California Press, 2001) p.1[/ref]. The discovery of this letter written by Kelly is a refreshing one, and one that allows us to springboard into the wider story of the opportunity for return to employment for these men.

Thomas Kelly’s letter (catalogue reference: LAB 2/1195/TDS2884/1919)

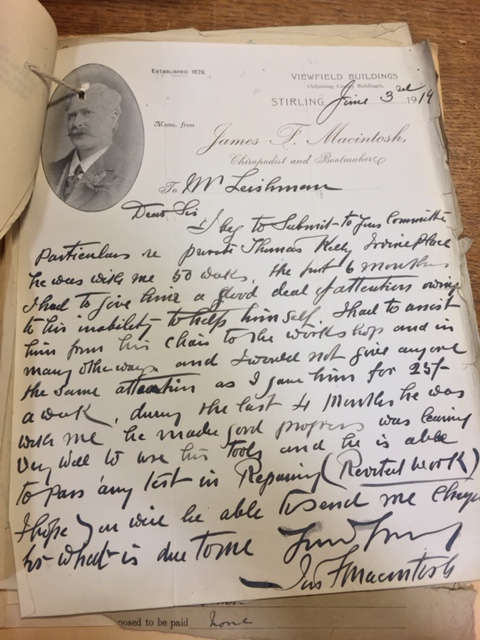

Training schemes to aid men such as Kelly were set up throughout the country. Many were linked to the more prominent limb-fitting hospitals, such as The Princess Louise Scottish Hospital For Limbless Sailors And Soldiers at Erskine in Scotland, and the Queen Mary Convalescent Auxiliary Hospital at Roehampton. Initially, Kelly received 12 months of training in boot repairing under the instruction of Bailie MacIntosh, Bootmaker, a private employer. However, even with such training, he was never able to obtain employment as a boot repairer and was advised that he was unfit for such work. Kelly received no pay during this training period except a one-off sum, essentially to keep him motivated. He was, however, receiving a full disability allowance at this time.

Letter from MacIntosh Bootmakers (catalogue reference: LAB 2/1195/TDS2884/1919)

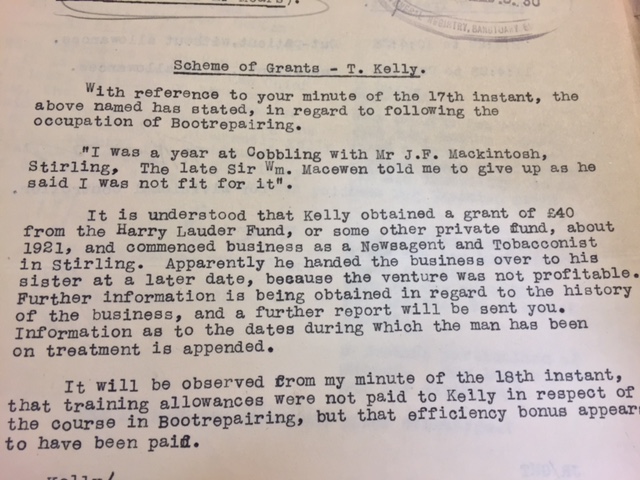

Not one to give up, it appears, Kelly then turned his attention to opening his own business, in the form of a Tobacconist’s and Newsagent’s, in 1921. Funded with his own money, he later received a grant for £40 to assist with keeping the business going. The grant came from the Harry Lauder Million Pound Fund For Maimed Men, Scottish Soldiers And Sailors. Set up by the well renowned Scottish singer and comedian, Lauder had a great deal of sympathy, and evidently support, for those who had been significantly injured in the war. Unfortunately for Kelly, he had to give up this business. Yet, once more, he shows a desire to be able to undertake some form of employment, which brings us to back to his letter regarding his desire to carry out more training – this time in the form of basket making, at Erskine House.

Scheme of Grants letter (catalogue reference: LAB 2/1195/TDS2884/1919)

That he wants to do this training at Erskine is significant: this facility was one of the leading in Great Britain with regards to limb production and rehabilitation. Workshops were erected in the grounds of hospitals in order to try and aid men with finding employment, and decent employment at that, once they had left the wards. Not just intended as a forward-looking scheme, the workshops were detailed with the task of employing the spare time of those waiting for treatment at the hospital in ‘useful and remunerative work'[ref]2. John Reid, The Princess Louise Scottish Hospital For Limbless Sailors And Soldiers At Erskine House (Glasgow: printed for Private Circulation, James Maclehose And Sons, Publishers To The University, 1917) p.43.[/ref].

This idea of usefulness surrounds the theme of rehabilitation, but was this usefulness in regards to the well-being of the man or was it more a means of making sure he was still a contributor to the economy?

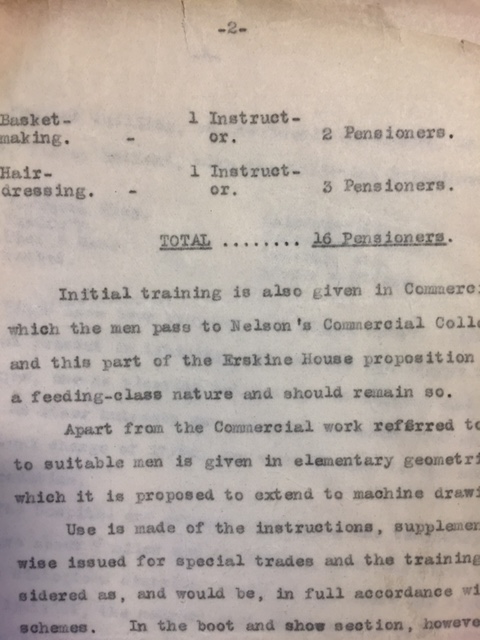

Numerous trades were taught in such workshops. At Erskine, the main departments within the workshops were cabinet making and carving, boot making, tailoring, basket making and hairdressing. However, anything from bookkeeping to bricklaying to driving could be undertaken in the various workshops that sprung up.

Erskine workshops (catalogue reference: LAB 2/1195/TDS3815/1919)

One document within The National Archives’ records suggests that a disabled man would not do for work such as that of a chauffeur. But was that really the case? There is evidence in some contemporary documents that would suggest otherwise[ref]3. The London Metropolitan Archives have some newspaper cuttings concerning this.[/ref].

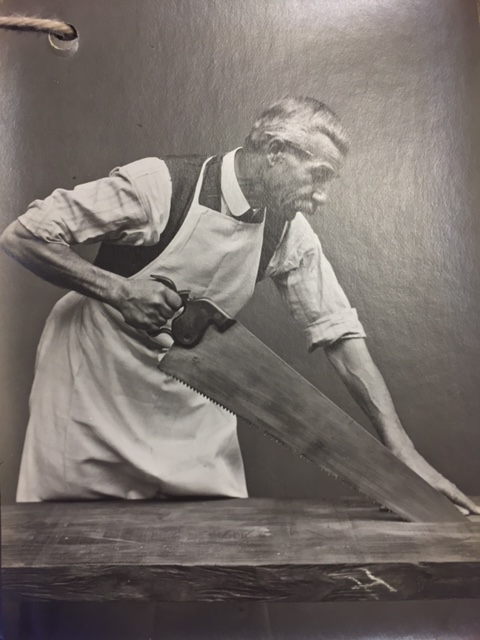

In order to aid men in this new employment, equipment and tools were adapted, especially for those who had lost an arm. In 1918, the Science Museum in London undertook some observations regarding how the body is utilised when using certain tools. Photographs were taken of a man as he used the most common tools that might be required for any of the trades being taught. These photographs were then examined to understand the different angles and movements that the body made when working, and these were, in turn, used to inform the adaptation of tools for the men who had lost limbs.

Science Museum observations (catalogue reference: MUN 7/331)

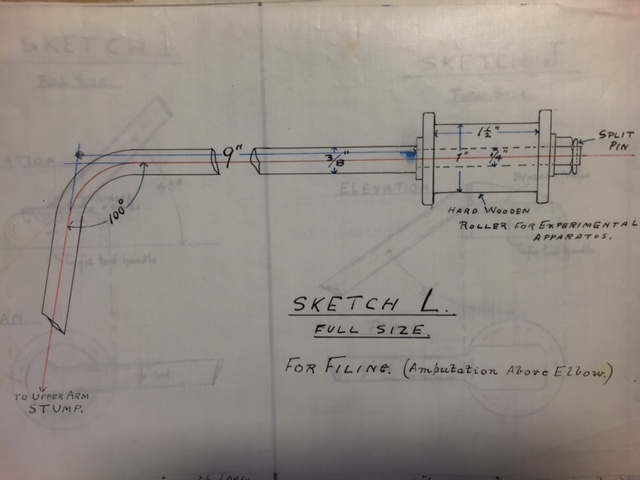

The same file also contains blueprints and sketches of how these tools could be adapted. On the sketch below, you can clearly see where the apparatus would be attached to a stump of the upper arm. All of this suggests a desire to make it easier for men to adapt to a new life after war. Yet, again, it could hark back to an idea of greed, and the belief that these men should earn their worth.

Plans for adapted equipment (catalogue reference: MUN 7/331)

Whether Thomas Kelly secured further employment is not revealed within the file. However, for many men who returned from the front with a missing limb, the outcome was more positive. At the end of 1923, the Ministry of Labour reported that 28,051 firms were now enrolled in the King’s Roll scheme, which asked employers to sign up and pledge to employ disabled ex-servicemen as 5% of their workforce (LAB2/1195/TDS165/2/1926).

Employment schemes, employment bureaux within hospitals such as Roehampton and the training made available all form an interesting lens through which to study disability history in the First World War. The LAB2/1195 files contain much more information on labour and disabled men, for anyone interested in finding out more.

Can you please correct ‘bureaus’ as the plural is ‘bureaux’.

There is a great deal of information about these courses in the University of Westminster Archive as many of them took place at our predecessor institution, the Regent Street Polytechnic. The Polytechnic’s Director of Education, Robert Mitchell, was seconded to the Ministry of Pensions as Director of Training and helped to establish the rehabilitation centres for disabled servicemen. The Polytechnic itself trained disabled ex-servicemen for trades such as kinematograph operator and hairdresser, as well as architecture, commerce and engineering, throughout the First World War and into the 1920s. The Archive holds both written records of these courses, and a photograph album documenting some of the individuals taking part.

Dr Ena Elsey was awarded a PhD for her research on the topic “The Rehabilitation and Employment of Disabled Ex-Servicemen after the Two World Wars” at the University of Teesside in 1995. At the time, Dr Elsey was one of very few people researching this topic. Her thesis is deposited in the University of Teesside Library.