Throughout 2015 hundreds of events are being held around the world to commemorate the 800th anniversary of the grant by King John of Magna Carta at Runnymede (Surrey) on 15 June 1215. New books have been published and incredible new discoveries have been made – including the recent identification of an unknown 1300 reissue of the Charter to the officials of Sandwich in Kent. Academics across the world are debating the importance of this totemic document, while the nation discusses its influence over a cup of tea. Today the official commemoration ceremony, attended by the Queen, is being held on Runnymede Meadows. Here at The National Archives we are hosting an education event, a Liberteas discussion and a panel debate ‘What’s so ‘great’ about the Charter?’ in the coming week to bring Magna Carta to life. But what are we commemorating, and why?

Magna Carta was negotiated and issued by John (1199-1216) as an attempt to prevent civil war between the king and his barons, which had erupted through John’s excessive financial demands and arbitrary rule. Also known as the Charter of Liberties or Great Charter, Magna Carta laid down many key tenets of good government and for the first time established the principle that everyone – even the king – was subject to the rule of law. For this reason it has come over the succeeding centuries to be seen as a cornerstone of democracy, particularly in the west, and as the foundation of many of the rights and privileges we enjoy today. Indeed, chapters relating to the freedom of the English church and cities, the right for anyone to have access to justice and the right for justice to be tested by one’s peers, survive on the English statute book to this day.

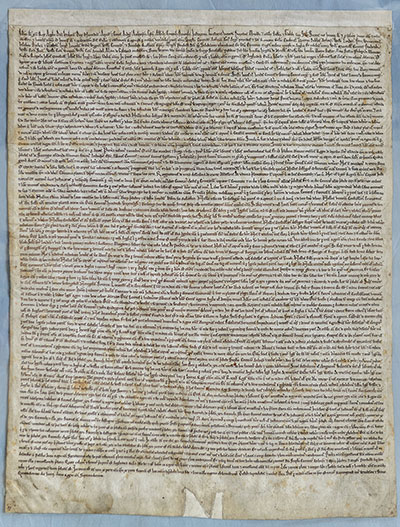

The Salisbury Magna Carta, 1215, by permission of the Dean and Chapter of Salisbury Cathedral

Readers may be interested, and surprised, to learn that The National Archives does not hold an original version of the 1215 Magna Carta. Whenever a medieval monarch issued a charter – a written expression of their will authenticated by a wax seal (charters were not signed) – lots of copies were made and sent out to officials throughout the kingdom and beyond so that the charter would be proclaimed and everyone would know about it. These copies are known as ‘engrossments’ and are all valid as original documents of the charter that was issued. At least 40 engrossments were sent out in 1215. Four only of these now survive – the ones sent to Salisbury Cathedral and Lincoln Cathedral, and another two (one of which has recently been identified as the engrossment sent to Canterbury Cathedral) which have found their way into the collection of the British Library.

Unfortunately, the copy kept by the king has not survived. What, however, we do have is a wealth of documents which tell the story of Magna Carta and put it in context.

Royal scribes would usually copy the contents of any new charter onto the Charter Rolls which essentially acted as the king’s file copy. The surviving rolls are here at TNA in series C 53. But, no copy of Magna Carta was entered on the relevant charter roll, probably because King John was never planning to adhere to the Charter.

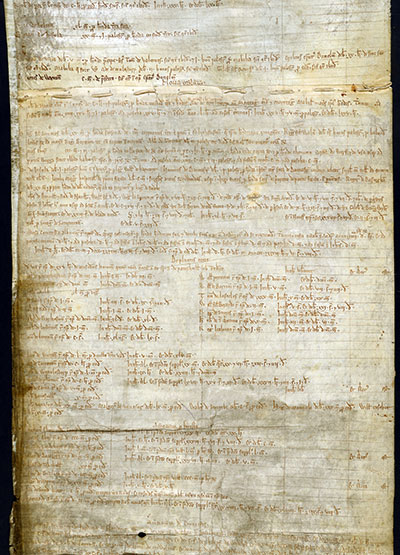

Pipe roll for Yorkshire, 1211-1212, showing new offerings to King John (catalogue reference: E 372/58, rot. 4, m. 2d)

The financial records of government tell us a great deal about the penalties John had tried to impose on his subjects. Rich widows, for example, could be forced to pay money to the king to avoid being made to remarry, or to choose their own husband, a useful source of income for the Crown. John, always short of money after his expensive military campaigns in France and Ireland, exploited this. In 1212, as shown by an entry on the Yorkshire section of this Pipe Roll – the central roll of government account – Hawise, countess of Aumale, was obliged to pay 5,000 marks – a huge sum – to the king not to be forced to marry again, and to be allowed to have her inheritance and dower. Hawise was a great heiress and had already been widowed three times. The rights of widows were addressed in clauses 7 and 8 of Magna Carta.

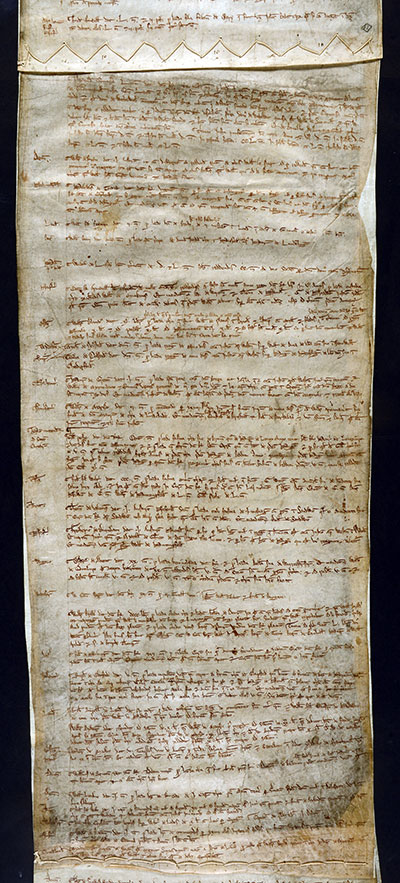

Similarly, when people wanted something from the king in the medieval period they were expected to pay a ‘fine’. Fines were paid for any kind of favour or privilege, such as the right to hold a market or fair or to have their debts repaid at a more favourable rate. King John abused this system and took extortionate fines from his subjects. This entry from 12 shows William de Briouze making a payment in kind – 300 cows, 30 bulls and 10 mares – to have his case against Henry de Nonant advanced. The fact that John made his subjects pay for justice caused a huge amount of anger and resentment. Magna Carta addressed this in clause 40, promising that ‘To no one will we sell, to no one deny or delay right or justice’.

Fine roll showing payments made for justice (catalogue reference: C 60/2, m. 10

In the short term Magna Carta failed to achieve its objective of securing a lasting peace. King John had the Charter annulled by Pope Innocent III within a few months and a violent civil war followed. John died in October 1216 and with a nine-year old as his heir and the heir to the French throne, Prince Louis, leading the barons, the young king’s advisors reissued Magna Carta in a slightly revised form soon after. Another reissue was made in 1217 along with the so-called Charter of the Forest, which addressed grievances relating to the oppressive operation of forest law. Then, upon coming of age in 1225 Henry III issued Magna Carta in a revised form. Included among the witnesses are some of the baronial leaders, including Robert fitz Walter, the self-styled ‘Marshal of the Army of God’. The National Archives holds a fine engrossment of this charter in the archives of the Duchy of Lancaster.

See more in our current display of Magna Carta documents in our Keeper’s Gallery.