Finding next-of-kin details for men who served in the Royal Navy and the Royal Marines can be fraught with difficulty. Even Royal Navy and Royal Marine service records – which began to be kept systematically from the mid-19th century onwards – rarely contain this information. However, for the periods 1795-1816 and 1830-1852, there are underused sources which can be used for this purpose, and which can also include details of service. There are 120 volumes containing such records in series ADM 27, under the deceptive description of ‘Registers of Allotments and Allotment Declarations’. These provide a vital link to Royal Navy and Royal Marine servicemen, their families, and much more besides.

But what are these allotment registers? To what do we owe their existence, and why are they such a potentially valuable source?

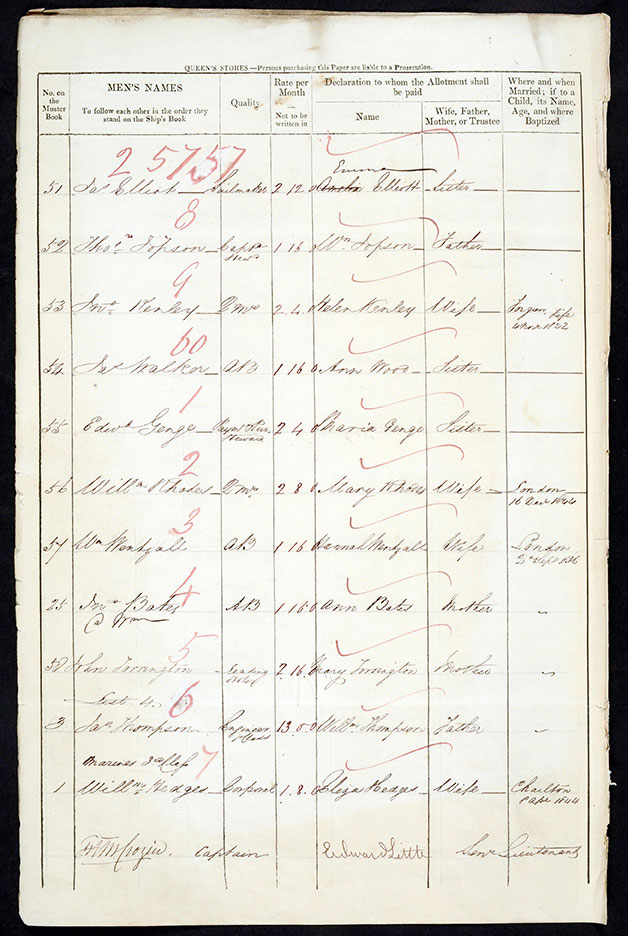

ADM 27/90 (318v): Alllotment of wages declaration list, June 1845

The Navy and Marines Act of 1795 (35 George III, c.28), firmly established the practice of allowing Royal Navy warrant officers and seamen (ratings) – and non-commissioned Royal Marine officers and other ranks – to send (allot) part of their wages to support next of kin at home. Previous legislative attempts to set up such a system in 1757 and 1792 had proved unsuccessful.

The 1795 Act was introduced mainly to improve working conditions and to make employment in the Royal Navy and the Royal Marines more attractive. This Act enabled naval petty officers and seamen (including landsmen), non-commissioned Royal Marine officers and other ranks serving at sea, to send part of their pay to their wives, children or mothers. Petty officers and non-commissioned Royal Marine officers could allot half of their monthly wages. Able seamen could allot five pence daily, ordinary seamen and landsmen could allot four pence daily, and a Royal Marine three pence daily. These sums were to be paid to designated next of kin every 28 days, commencing from the date of an allotment declaration signed by a serviceman who opted into the allotment scheme. Later, under the Navy Pay Act of 1795 (35 George III, c.95), Boatswains, Gunners and Carpenters were also allowed to send half of their monthly wages for the maintenance of wives, children or mothers.

This allotment system was innovative as it sought to reduce the hardships of families whose main breadwinner was away from home – in some cases for many years. It also eased the worries of servicemen as it ensured that their loved ones had a regular income. Moreover, it made service in the Royal Navy and Royal Marines more appealing: there was no comparable allotment system in the Merchant Navy (with which the Royal Navy competed for labour) or the Army. The permissions granted under the 1795 Act were extended, allowing all naval ratings to allot one half of their wages to wives or mothers from 24 April 1797.

The take-up of men opting into the Allotment payment system started sluggishly. In 1796, out of 105,708 men serving in the Royal Navy, 3,346 (one man in every 32) chose to send part of their wages home. By 1800, this had risen to 13,582 (one man in nine) out of 118,247 serving. In 1812, it was 27,019 (one man in five) out of 138,204 serving. The Allotment registers were kept by the Allotment Office to record details of men serving in the Royal Navy and Royal Marines making such payments.

Previously, the way in which the records in ADM 27 were catalogued meant they were very difficult to search. Being listed by year, and by ranges of initial letters of ships’ names or by allotment declaration number, meant that they were virtually impenetrable. Many records had to be searched in the hope that they might contain a specific ship’s allotment register or allotment declaration list.

Excitingly, this has changed significantly, following the efforts of a team of volunteers and the Friends of The National Archives: they have completely indexed these 120 Allotment registers in ADM 27 (I was lucky enough to be the project manager coordinating this effort). This huge and significant undertaking has resulted in over 450,000 Allotment Register entries being made available to search on The National Archives catalogue, Discovery.

- ADM 27/90: Allotment of wages from James Elliot, HMS Terror, to his sister Emma Elliot, misnamed as Amelia Elliot, June 1845

- ADM 27/90: Allotment of wages from James Elliot, HMS Terror, to his sister Emma Elliot, misnamed as Amelia Elliot, June 1845

These Allotment registers can now be searched by person’s name and ship’s name. Each accompanying catalogue entry provides a full document reference and folio number. It also gives

- the name of the ship the allotter served on

- his rank or rating

- the name and relationship of his next of kin

- the year of allotment

For the period 1795 to 1816, it can also provide a reason why an allotment payment ended – for example, if the allotter was discharged to another named ship or died in service.

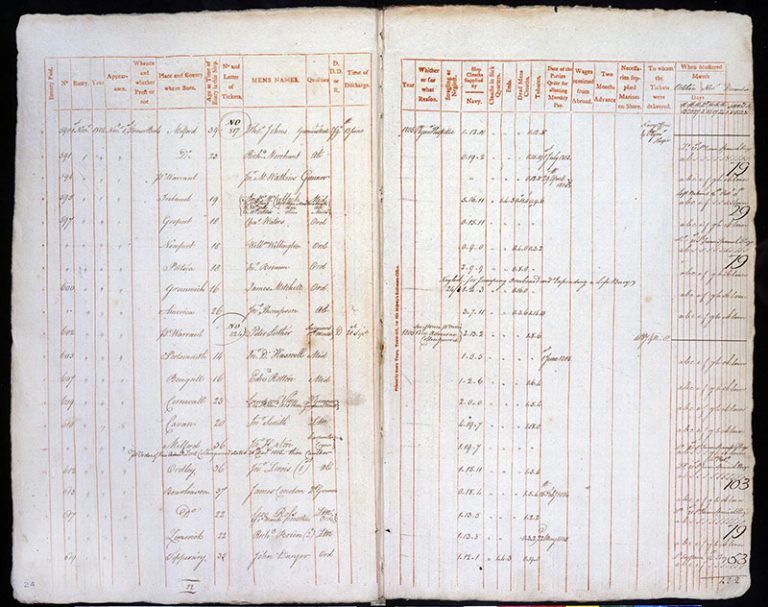

These catalogue entries will also provide an individual’s ship’s muster book number (unique to the person), which can be found in a ship’s muster or pay book. These can also be searched by ship’s name and date on Discovery. The importance of this number becomes apparent when searching the musters of ships manned by upwards of 700-800 men. It is worth noting that ships’ musters from 1761 can provide a serviceman’s age and place of birth.

ADM 36/15955: Ship’s Musters, Dreadnought, 1805-1806

Multiple catalogue results for the same person in the ADM 27 series will enable researchers to piece together an individual’s service career at a glance. This is particularly important in a period for which service records do not exist. (These records were introduced in 1853).

ADM 27 Discovery results can also lead to extra information in the registers themselves (available digitally for free on site in our reading rooms, or through the FindMyPast website). They can potentially reveal numbers of children and where families resided for the period 1795 to 1816. For the registers dated 1830 to 1852, there is also the possibility of finding a date and place of marriage, or a child’s birth details.

Were these allotments still being made in 1916?