Last month was Disability History Month. Founded in 2010, it endeavours to highlight the history of disability. To help open up our collections here at The National Archives we have recently published a research guide to point out some of the sources that might be a useful starting place. For this purpose we have defined ‘disability’ widely in the way it has been historically treated to include sensory impairments such as blindness and deafness.

Without necessarily realising it, most people that use our records will have encountered the history of disability. Before working here I had unwittingly come across many instances of disability history while researching my family history. As many people do, I began with the census, one of our highest used series of records.

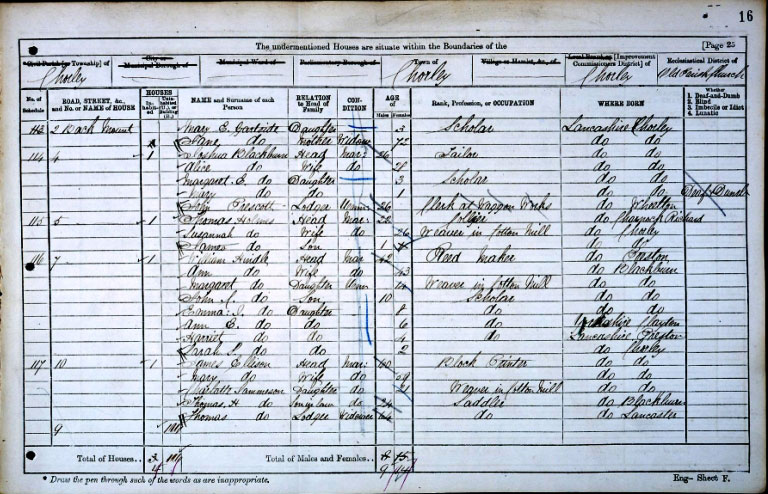

In this example from Chorley in 1871 the farthest column on the right holds the starting point of information regarding disability, listing as it does here Mary Blackburn who is noted as ‘deaf and dumb’.

From 1851-1911 the census included some kind of indication of mental and physical disabilities, including learning disabilities. Rather than giving statistics or just listing impairments, the census records give names, and to some extent identities, to people with disabilities from the past who would otherwise have been anonymous. It provides an overview of how individuals may have been affected by disability, and where censuses were taken in an institution, shows where the institutionalised disabled were housed. Although disability is an under-researched and historically marginalised issue, for many it is and was a fact of life. Therefore in our records it is an area of recurring interest.

To find sources that refer to disability it is necessary to adopt the contemporary terminology. This is often language we now find offensive. Disabled people haven’t always been perceived as they are now. This not only reflects the attitude of the time, but the medical developments and the general evolution of language. The terminology used on the census demonstrates this, including words such as ‘dumb’, ‘lunatic’, ‘imbecile’, ‘idiot’, ‘asylum’ and ‘inmate’ [see disability research guide]. Over time attitudes to many of these words have changed and we would not use them today.

Another pitfall of language is the historical lack of clarity, as the 1881 Census Report explained;

‘it is certain that neither this nor any other definite distinction between the terms was rigorously observed in the schedules, and consequently no attempt has been made by us to separate imbeciles from idiots. The term lunatic also used with some vagueness, and probably some persons suffering from congenital idiocy, and many more suffering from dementia, were returned under this name.’ [ref] 1. 1881 Census Report, PP 1883 LXXX [c.3797.]. [/ref]

The role of language in our records is therefore complex. Yet without using this language to access the records this history remains largely untold.

Since launching our research guidance on Lesbian and Gay history, using contemporary language has enabled us to uncover a wealth of relevant records in our collection. In doing this we have started to open up relatively unchartered areas of our records. Additionally, over time words have been reclaimed such as ‘queer’. To catalogue our records with modern language would be naive. Who’s to say the language we currently use will be acceptable to future audiences?

Despite the positive results it is something we find a constant challenge and debate it within our work. We want the information in our records to be as accessible as possible and believe it’s better to challenge the language of the past and put it in context rather than ignore it. In using the terminology to start searching I have already unearthed several exciting documents from our shelves.

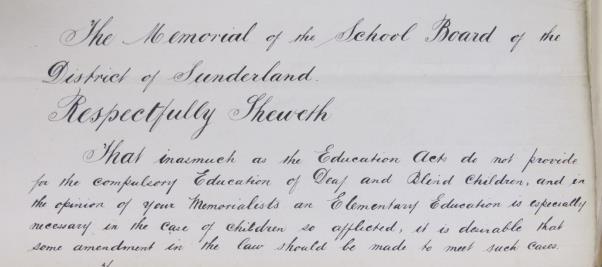

In 1885 a Royal Commission was launched to look at the welfare of the ‘deaf, dumb and blind’. Correspondence in the series ED 50 contains discussion on the educational element of this. In the nineteenth-century patterns of reform for more humane treatment began to show. These records are interesting as the nature of the commission allows a range of opinions to be presented on the subject, including key reformers as well as government officials. A recurring theme of the petitions attached to this is the demand of education for all, including children with impairments. This became the Elementary Education (Blind and Deaf) Bill in 1893. It signals a change in treatment to one of relative inclusion, as demonstrated in the memorial above from the Sunderland District School Board.

Amongst these snippets of history I came across a press cutting that I assumed was another example of people speaking on behalf of the deaf in nineteenth-century society, in an opinion piece regarding speech education from ‘The Deaf and Dumb Times’ dated January 1891. The monthly publication describes itself as ‘Being an organ intended for the Welfare of the Deaf and Dumb’ edited by C. Gorham.

Charles Gorham founded and edited this publication, and was himself deaf. The proprietor Joseph Hepworth regularly contributed to the publication and had lost his hearing at the age of eight. Both were crucial in facilitating this space for deaf people to discuss issues important to them and to have a voice in society. The newspaper encouraged debate and opinions of people with an interest in deafness. Their columns presented arguments in support of the ‘finger alphabet’ or sign language and the combined method of signing and lip-reading. This opposed the government position which supported lip-reading as the primary form of communication.

This publication is a brilliant example from our collection of the voice of deaf people in the past and their active political agency that had the potential to inform medical and political discourse. The National Archives records offer a great opportunity to re-present disability. This history often gets hidden by what is now perceived as negative language. With the centenary of the First World War approaching it is particularly important to look at disability and how warfare affected its prevalence in society. I would urge you to give it a go and research this vast and fascinating area of history.

As part of diversity week this Friday we have a talk on Learning Disabilities by Simon Jarett – another related and under-researched area of our collections.

Meanwhile this is a new area for us. If you have any comments or suggestions on the research guide please get in touch.

The following may be of interest to researchers in relation to ‘What records can I find in other archives and organisations?’

The Children’s Society Archive has two projects that can provide a wealth of information about disabled children and young people during the Victorian and Edwardian eras. More information can be found on the Archive’s Hidden Lives Revealed website through:

1) The Archive’s ‘Including the Excluded’ Project http://www.hiddenlives.org.uk/including_the_excluded/ and the project blog: http://chilsoc-blog.ilrt.bris.ac.uk/category/including_the_excluded/

and 2) the Unexplored Riches in Medical History Project that aims to catalogue, preserve and highlight the wealth of disabled children and young people and medical information hidden amongst the children’s case file records in The Children’s Society’s archive. The Unexplored Riches Project is supported by funding from the Wellcome Trust’s Research Resources in Medical History grant scheme: http://www.hiddenlives.org.uk/unexplored_riches/ and the project blog: http://chilsoc-blog.ilrt.bris.ac.uk/category/unexplored_riches/

Another term which appears in records and therefore the catalogue are ‘mentally handicapped’ (see T 227) or ‘handicapped’ or ‘handicap’ as well as ‘congenitally disabled’ in the case of Thalidomide victims.