The first part of this blog covered the initial search for records relating to Amphipolis, but as this was not particularly successful I then looked elsewhere in Macedonia, at a wider area where other antiquities had been discovered by British troops. Sometimes these came as a result of work on the ‘Birdcage Line’ defences on the outskirts of Salonika. One of these discoveries was a tombstone found by 7 Battalion Wiltshire Regiment, while 8 Battalion Royal Scots Fusiliers found a memorial plaque from the Roman period dedicated to Salarius Sabinus, a military contractor.

These two battalions were part of 26 Division, so I searched through the most likely battalion, brigade and divisional war diaries. However, the results were again quite disappointing as the records were incomplete, difficult to read or lacking useful details. I also looked at some of the diaries of XVI (16) Corps, as the Struma front was under its overall command throughout the campaign, but they too had nothing obvious to say about archaeology. Instead, they recorded other details such as adverse weather, flooding in the Struma valley and even a plant collecting competition.

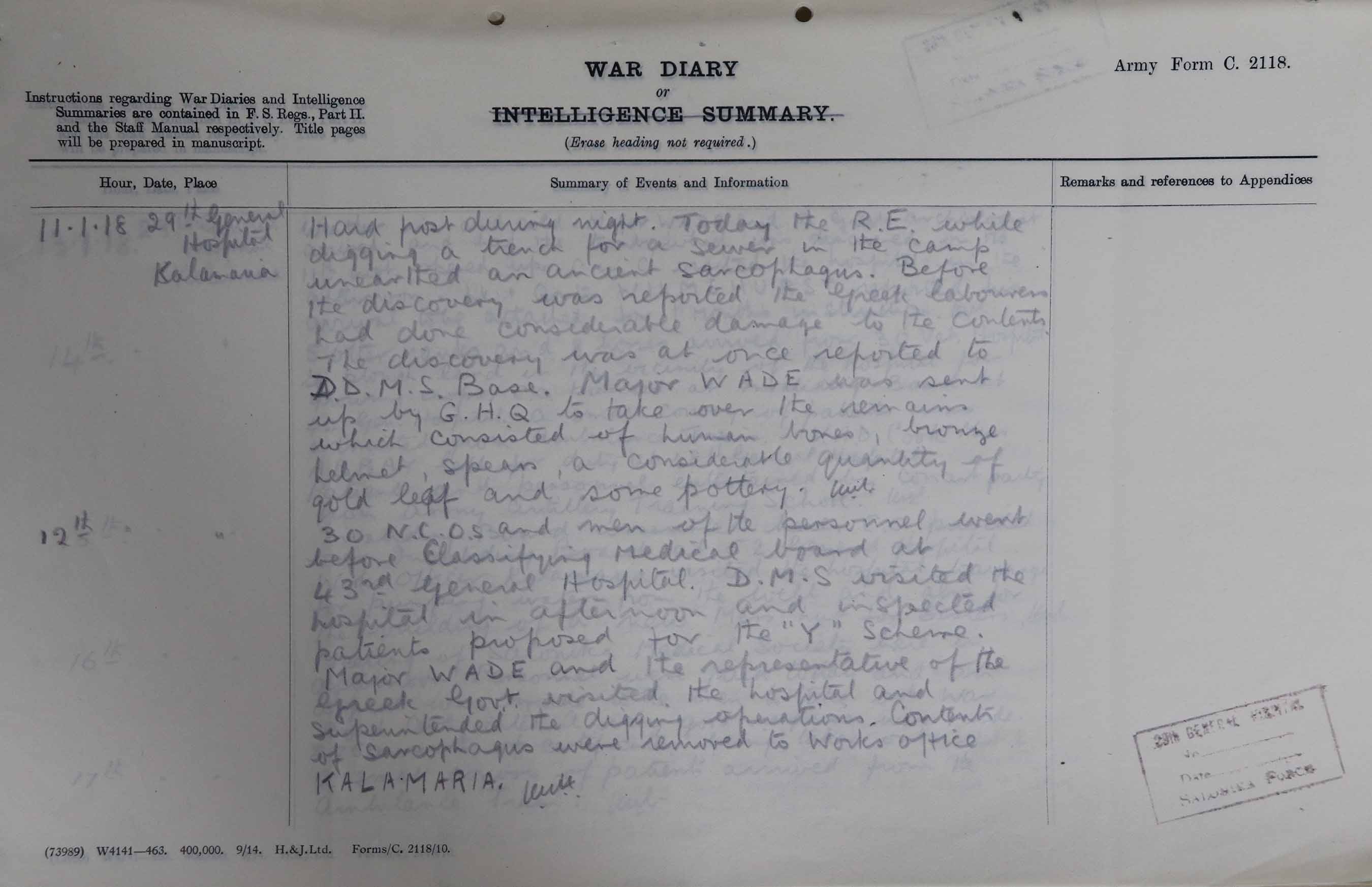

In January 1918 a burial with bronze objects was found at Kalamaria, during digging for a sewer near 29 General Hospital. This time the war diary does mention the discovery, which included human bones, a bronze helmet and gold leaf.

British archaeological finds were first placed in an informal museum in the White Tower in Salonika, until another building was found later. The Salonika Base Commandant diary (WO 95/4946) makes no mention of the White Tower, but there is a general routine order from June 1918 which states that the new museum was open to Allied troops (WO 95/4768). Greek approval was also sought for the establishment of the museum and display of the finds.

Apart from the war diaries, I also looked at Foreign Office records, and found one document from 1919 that mentioned the British Salonika Force collection and its move to the British Museum in London. It also points out that the Greek authorities had granted permission for this transfer.

Goodbye Neohori, farewell Tafel Kop

The research overall was much more difficult than I expected, and offered quite limited evidence for the Amphipolis tomb and town. The failure to find any mention of the Amphipolis Lion was a surprise, given the size of the sculpture. The wider search in the war diaries revealed only one specific mention of an archaeological discovery and a few of the general orders. However, it was quite clear that the Amphipolis tomb site itself was never occupied by British troops prior to the armistice.

On the other hand, only part of the British Salonika Force could be covered in this research, which may leave scope for further investigation in other war diaries, perhaps those covering work on the Birdcage Line.

As for the photograph of the four men holding the skulls (shown in part 1), it was definitely not taken at the Kasta Hill tomb. Unfortunately, the 2 KSLI war diary (WO 95/4889) offers little further explanation; the battalion began work on trenches at Neohori in August 1916, and remained in the area to the end of 1917.

Dear Mr. Michael McGrady,

Thank you very much for this very useful information regarding the British troops at Amphipolis during WWI. Just a piece of additional information regarding the lion statue. The British army could have seen only bits and pieces of it near Struma river, south of Neohori (Ancient Amphipolis) as the pieces were put together to create the lion one can see today in the 1930s. Please see Oscar Broneer, The Lion Monument at Amphipolis, The American School of Classical Studies in Athens, Harvard Univ. Press, 1941. According to this book, some of the ruins of the lion were indeed seen by the British troops which failed to move them from the spot they were located.

Thank you again for the research and the publication on this page of the official documents and maps.

Demetris Loizos,

History Professor (retired)