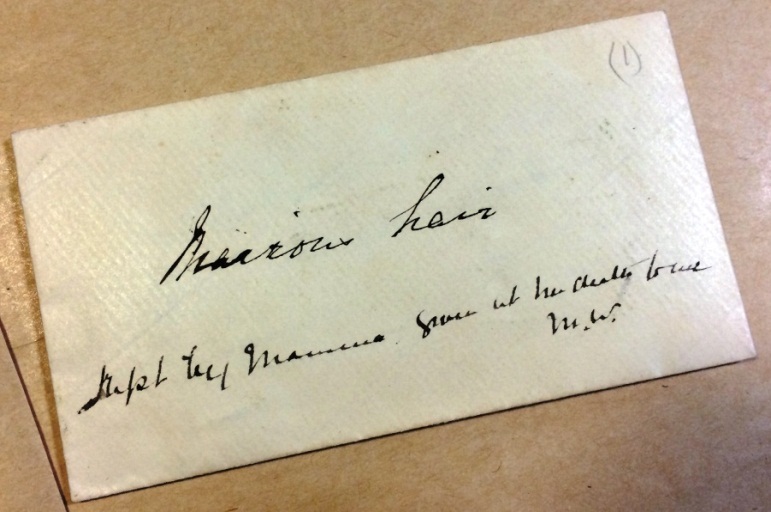

Lock of her hair at age of four months from the papers of William Evelyn Wylie (catalogue reference: PRO 30/89/37/1)

Hair has long been used as a memento, a physical means of remembrance, of someone gone or separated by distance.

But why would you find this in a government archive?

An archive is inevitably a hive of the unexpected, but being asked to write about locks of physical hair in our holdings was my most unexpected challenge yet.

As I started my search I had no idea what I might find.

Locks in the archive

An envelope labeled ‘precious hair’ from the papers of William Evelyn Wylie (reference: PRO 30/89/37/1)

Samples of hair make their way into our collections in the most curious of ways. Chancery proceedings against jewellers commissioned to make rings hold long-forgotten letters of clients with the locks of hair still present, carefully folded in the letter. Or they find their way into personal papers where a child’s curl of hair might have been preserved as a memory of youth. A sample of hair even makes it to the crash report of an aircraft in Belgium, 30 May 1940, reporting the deaths of the inhabitants (AIR 81/696).

But why was hair preserved? Before popular photography, hair provided a keepsake and a memory, an interest that peaked in the sentimental 18th and 19th centuries. Hair was sometimes preserved in a significant book, scrapbooks, letters, and even in the elaborate form of jewellery.

In the selection we hold here there is a range of different reasons and motives to why the hair was preserved, and what it tells us about the individual.

A lock of love

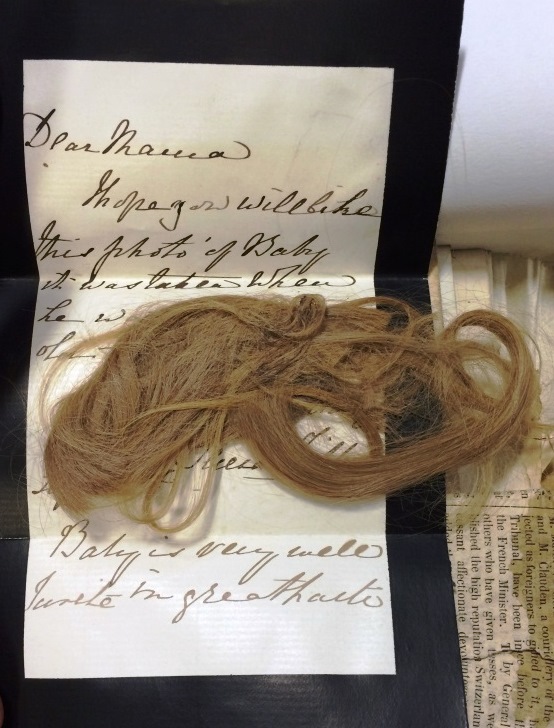

Correspondence relating to the Tichborne case, including a lock of hair from 19 January 1829 (reference: J 90/1225)

In PRO 30/89/37/1 there is a lock of hair in a delicately labelled envelope noting ‘Lock of her hair at age of four months’ in the private papers of Mrs RB Wylie (née Marion Drury). The hair of this child is preserved with the family papers amongst school records and other family ephemera. It shows the family’s desire to celebrate the new life, and in an age before wide-spread photography was a way of sharing pride in the child’s birth with friends and relatives. In this specific case the letter was never sent, the lock of hair was preserving the memory for themselves.

Another example of a blond lock is in case relating to the Supreme Court of Judicature with an attached letter that concludes with the lines ‘Baby is very well’ (J 90/1225). While the personal papers of Edward Law, 1st Earl of Ellenborough contain parcel after parcel of hair wrapped in paper relating to the many members of Lady Ann’s family – all delicately labelled with the age of the child.

Sometimes situations were not so happy, in times of high infant mortality rates hair was preserved by families of dead children, similar to Victorian mourning dolls, which were often commissioned after the death of a child.

The hair of family members is not always recorded for positive reasons, a lock of hair in found in the records of the Supreme Court of Judicature centres around the Tichborne v Castro case (1868 T 41). In this instance the hair is used as evidence of heritage; when Roger Tichborne went missing at sea in 1854 and an individual claimed to be him the court compared previous clippings of his hair to the individual in court. The claimant was ultimately found guilty of perjury.

A crown of hair

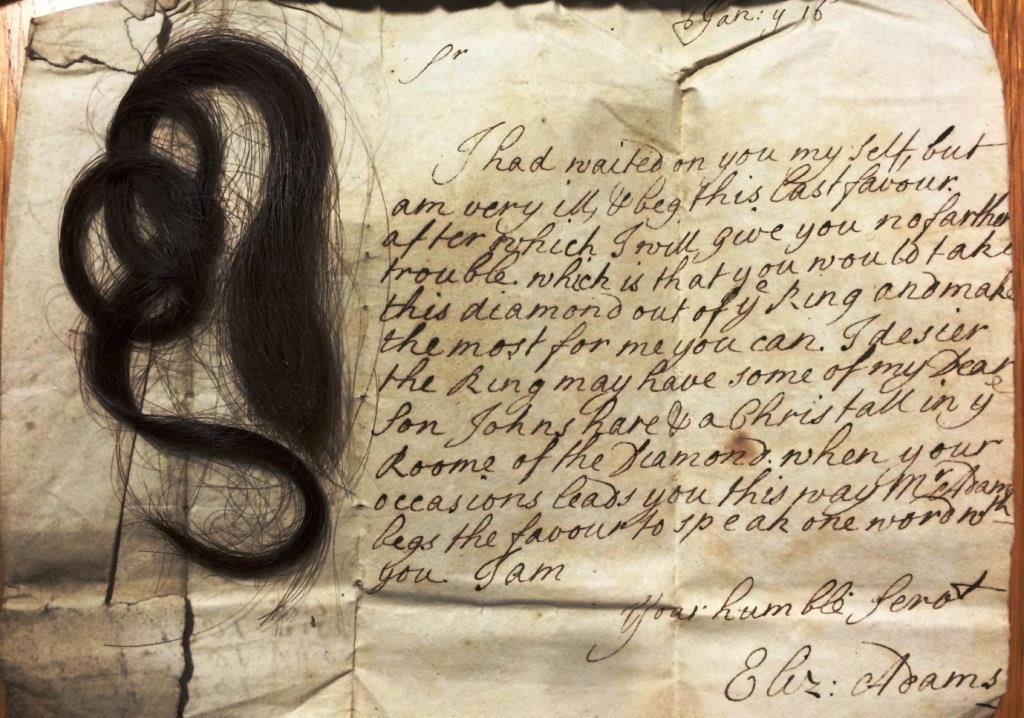

A long length of hair is found in another letter concerning a child. This time the letter requests a ring to be made with her ‘dear son Johns hare [sp] and a crystal in the room of the diamond'(C 104/197). While these types of rings themselves would have been valuable, the sentimental value is key.

A letter enclosing a lock of hair (still present) to be placed in a crystal for a ring from the case COPE v COPE (reference: C 104/197)

It is remarkable (and slightly creepy) to note the condition of the hair which is over 300 years old. Hair was a symbol of life, with its ability to survive so well.

Hair could be woven into jewellery, such as brooches, rings and chains. Locks of hair were given as gifts to an unrequited lover, or their ‘sweethearts’, and romantic cards were often sent with hair woven into the design, especially as the modern concept of Valentine’s Day developed in the 19th century. Designs could be developed by professionals, but often women wove designs by hand.

In another example found in Chancery proceedings C 114/84 it is interesting to note it is not a child or lover’s lock of hair being preserved but that of a friend as requested by Mrs Hatch to bear her initials. It begs the question that with the lock and the letter in our collection – was it ever made?

The only striking absence I can see from my research of The National Archives’ collections is the lack of a lover sending a lock.

But maybe it’s there, a curl of hair, hidden deep in some dusty records, waiting to be found – why not have a look for yourself?

Those locks look massive! They must have had a lot of hair in those days, especially the babies!

I also have a lock of my wonderful WIFE , “LOIS JOANS “hair as a memento of her life”,

Its really a very good and new way of presenting love locks to our partners.

Very interesting! I work with government records myself, and found a lock of hair in a (male) prison inmate’s case file from a female companion; the prison employees seem to have confiscated it before it reached the inmate and put it in his file, along with a love letter that came with it. Who knows how many other locks are lurking in our records?

Thank you all for your comments.

Anjanette that sounds like a facinating document, and certainly illustrates the random ways locks of hair end up in archival records!

I found a locket of hair in a Civil War Pension record of my great great great grandfather’s. It was wrapped in a Bible page with wedding dates, as supposed proof of marriage.