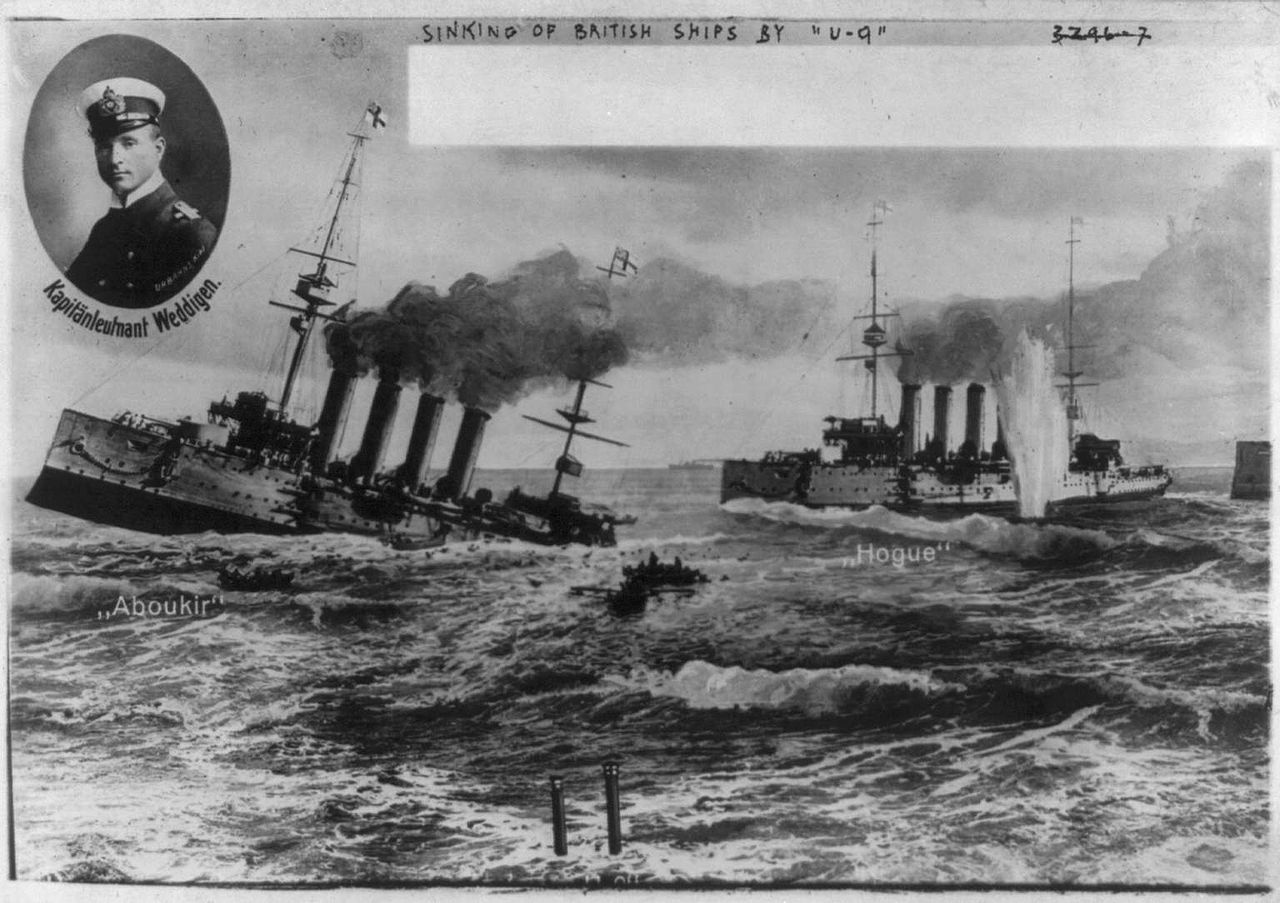

In the space of little over an hour on the morning of 22 September 1914, the Royal Navy suffered one of the worst disasters in its history. Three armoured cruisers were sunk with the loss of over 1,450 lives. The culprit, U-9, a small German submarine with a crew of less than 30, slipped away unharmed. This battle fundamentally changed perceptions of warfare at sea, and set the tone for the very modern maritime conflict to be fought over the next four years.

Early in the morning of 22 September 1914, three old British armoured cruisers, Aboukir, Cressy and Hogue, were patrolling in the southern North Sea. These vessels were supposed to be the first line of protection for the transports ferrying British troops to France; strong enough to resist a minor German attack or forewarn of a major one. The ships themselves were ill suited to this task. Although barely 10 years old, the pace of naval development meant that they were comparatively slow and poorly armed. This, combined with the proximity of their patrol to the German coast, led to them being nicknamed ‘the live bait squadron’. [ref] 1. Winston S. Churchill, (1923) The World Crisis, Volume I Pg. 323 [/ref] On 18 September Winston Churchill, the First Lord of the Admiralty, instructed that the ships ‘ought not to continue on this beat. The risks to such ships is not justified by any service they can render’. For reasons of internal Admiralty politics this order was never enacted.

That morning the three cruisers were steaming north at the relatively leisurely pace of 10 knots, conserving coal. Captain John Drummond of the Aboukir was asleep below decks when the torpedo struck. He told the Court of Enquiry that he ‘felt the explosion and went out of my cabin at once. I saw water had been thrown up and still in the air and smoke or dust seemed to be coming up through the ship’. The officer of the watch, Lieutenant Commander Edward Cloete, was equally surprised having seen no sign of any submarine. He told the enquiry that he believed the explosion had been caused by a mine rather than a torpedo. ‘The ship listed over almost at once until the upper deck on the port side appeared to be 2 or 3 feet above the water’ and it quickly became evident that efforts to save the ship were in vain. Drummond ordered the other two ships of the squadron to close on the Aboukir to provide assistance. Ten minutes after the explosion the ship began to sink, ‘the list increased rapidly and loose wood was thrown overboard and the men told to jump overboard’. The Aboukir rapidly capsized (ADM 1/8396/356, ADM 137/47, ADM 178/13).

Captain Wilmot Nicholson of the Hogue saw the disaster aboard the Aboukir unfold. He immediately closed with the sinking ship to offer assistance. Nicholson told the Court of Enquiry that he had intended to ‘steam through the survivors giving them what assistance I could and then to proceed to the trawlers in vicinity’ in order to get them to help the Aboukir’s crew. He was clearly aware of the threat from submarines as he signalled the Cressy to look out for them. In reality Hogue was stopped for some time near where the Aboukir had gone down, partly as a result of delays in launching her boats to help the survivors. Nicholson reported that he had just ordered the ship back underway when she was struck by two torpedoes. In the process of launching the torpedoes the submarine briefly came to the surface and was fired on by both the Hogue and the Cressy, but neither hit her. Following the explosions the Hogue ‘began to take a heavy list to port’ and it was rapidly apparent she was sinking. Nicholson ordered ‘the men to save themselves as best they could’. The Captain reported that ‘from the time we were struck until the ship finally sank could not have been more than ten to fifteen minutes’ (ADM 137/47).

Captain Robert Johnson of the Cressy clearly understood the threat posed by submarines, and having sighted the U-9 on the surface ‘he gave the order ‘Full speed ahead’ but the Hogue was struck almost immediately afterwards. He then said he would take his chance and stand by the other two ships’. This decision cost Johnson his life, and the lives of hundreds of members of his crew. Shortly after the Hogue capsized U-9 fired two torpedoes at the Cressy, the first hit whilst the second passed under the ship’s stern. The damage was reasonably well controlled and it seemed possible that the ship would survive; then, 15 minutes after the first attack, U-9 fired her final torpedo at close range. The Cressy rolled over onto her starboard side and sank at 7.50am (ADM 137/47).

As soon as the first torpedo struck the Aboukir the British ships were signalling for reinforcements, particularly of light craft, to assist them. Despite this the first British warships did not arrive on the scene of the disaster until 10.45 am. In the meantime many of the survivors were picked up by British trawlers and two Dutch steamships, Flora and Titan.

The German submarine U 20. U 20 was larger than U 9 and became infamous for sinking the passenger liner Lusitania (ADM 137/1246)

The loss of three old cruisers was largely immaterial to Britain’s naval supremacy, however the event shocked the Navy and the nation. Britain had lost over 1,450 sailors, many of whom were either middle-aged reservists with wives and families at home or young naval cadets recently released from the training school at Dartmouth. Their lives were laid down, not in pursuit of some glorious victory, but vainly fighting an unseen and unattackable enemy. This battle firmly brought home the realities of modern industrial warfare. The result was that at 23.00 on 22 September the Admiralty issued an order to the fleet stating ‘it must henceforth be recognised by all Commanding Officers that if one ship is torpedoed by a submarine or strikes mine, the disabled ship must be left to her fate’ (ADM 137/47).

RIP Robert Abbott my gt gt uncle who died on the Cressy.

[…] The ‘live bait squadron’ […]

RIP Thomas E Drake stoker 1st class HMS Aboukir my great uncle

John Hogan RNR AB sailor age 34 on 22 Sepember 1914 and the day of his 7th Wedding Anniversary perished in the sinking of HMS Aboukir.

Leaving his wife and three small children the youngest 3 months old. His wife (my grandmother) died 1919 it was said of a broken heart. The children were then placed In an orphanage, where they were treated not as a hero’s children but with the harsh reality of the times.

One of those children was my father he being the eldest boy named after his father John.

The disaster that took place on the 22nd September affected many lives around the country, but to me it does seem to be brushed over when WW1 ever is viewed by most of the media.

My 2 x great uncle Harry Hammond went down on this day on the HOGUE.

I would love to find a photo of him. I am intouch with his grand daughter and she dont have any of him either.

R.I.P.

All who went down on the 3 ships that morning.

In memory of my Grandfather, William Alfred Fox, Able Seaman Stoker Ist Class, who went down with The Hogue.

Unfortunately this disaster should of been avoided, but submarine war fair was new and they were writing the rules as they went along. In ww2 convoys would never stop so the poor men were left to their fate. All understood they couldn’t as then they would become a target. If you were badly burned by oil or steam it was thought best to let the sea take them quickly rather then die a slow painful death! It always amazes me to what lengths we will go to to kill one another, people will travel incredible distances so they can kill, there seems to be no lengths we will not go to!