As the official archive for the UK Government, one of the challenges of research at the archives is getting a sense of the living and breathing people within the records we hold. Nonetheless, there are voices in the records if you listen for long enough.

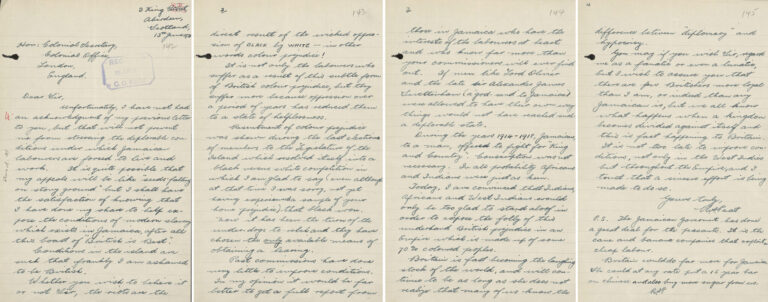

On 13 June 1938, an individual named R. S. Peat sent a letter to the Colonial Office in London from Aberdeen, Scotland. Little is known about the writer, who powerfully outlines what they see as the ‘deplorable conditions’ Jamaicans faced in the Caribbean in the 1930s and 1940s.

Today, the letter is found in CO 137/827/1, a record containing multiple perspectives on the economic and social issues people faced, specifically in Jamaica, and advice on solving them in 1938 when tensions came to a head. Alongside the state records in the file – including an article by George Padmore and correspondence from the then Governor of Jamaica – R. S. Peat’s letter stands out for the vivid and personal language used.

Read a transcript of the letter

Written nearly 10 years before migration to Britain from the Caribbean increased in the post-war period – most symbolically through the arrival of the Empire Windrush in June 1948 – and while written in the UK, the letter provides a unique insight into this period in history through a distinctive voice. To try and understand this past more fully, we have recorded an audio version of the letter, which helps us get a sense of the person behind the record and bring their language and imagery to life.

Listen to an audio version of R. S. Peat’s letter by our volunteer reader Des Shillingford:

The letter has also been digitised as part of our classroom resources.

Read a transcript of the letter

Jamaica in the 1930s

In the 1930s Jamaica’s economy was struggling. The unequal distribution of land between the landowning minority and the labouring majority had resulted in a stagnation of the economy where most Jamaicans were heavily dependent on agriculture, and the unreliable cultivation of bananas, sugar, and other produce. The inadequacy of the earnings of a typical labourer had fallen behind the cost of living, leading to discontent amongst mostly Black Jamaicans who worked on large plantations in poor conditions. [ref]The spread of disease through poor sanitary and living conditions, had also led to many young children dying of hookworm. The National Archives holds records of health campaigns organised by the Colonial Office, particularly warning people of hook worm in colonies such as Borneo and Grenada. CO 874/872, CO 321/287/11, CO 321/287/12, CO 123/292/40[/ref]

At this time, the well-known journalist and pan-Africanist, George Padmore declared: [ref]Writing in International African Opinion, Vol. 1, No. 1, July 1938. [/ref]

‘Used as we have now become to descriptions of the manner in which great masses of people within the Empire live, even a brief review of the conditions of the Jamaican workers comes as something of a shock.’

George Padmore

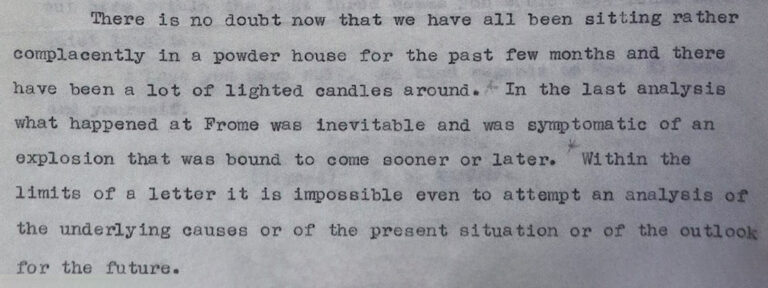

Few workers were permitted to vote and although trade unions were legal, unlike elsewhere in the British Empire, members were not able to peacefully picket and were not protected should they break their contracts due to strike action. [ref]It was not until 1944 that all males and females 21 years of age and over were able to vote in elections. See Maurice St. Pierre, “The 1938 Jamaican disturbances: a portrait of mass reaction against colonialism”, Social and Economic Studies 27, no. 2 (1978): 171–96. [/ref] The much-respected barrister Norman Manley wrote of the ‘situation’: [ref]Norman Manley in a letter to R.L. M. Kirkwood, West Indies Sugar Co. June 22nd, 1938. CO 137/827/1. [/ref]

‘There is no doubt now that we have all been sitting rather complacently in a powder house for the past few months and there have been a lot of lighted candles around.’

Norman Manley

‘There have been a lot of lighted candles around’

In 1938, tensions reached a boiling point at the Frome Estate on the island. Specifically, at the new sugar factory of Tate & Lyle. On 2 May 1938, an anxious telegram was sent from the Governor of Jamaica, Edward Brandis Denham, to the then Secretary of State William Ormsby-Gore. Received at 01:55 the next morning, the telegram described how disturbances had occurred at the Tate and Lyle estate in Frome, in the most western parish on the island, and had developed into a 3,000 strong crowd of striking workers. In the telegram Denham writes: [ref]CO 137/ 826/9. [/ref]

‘Reports received today indicate that crowd of/fully 3,000 strikers demolished the Company’s office at Old Frome, attacking the staff and police with stones, sticks and iron bars necessitating immediate firing by the police. Two killed, about 11 wounded, 30 arrests made.’

Edward Brandis Denham, Governor of Jamaica

In total, four striking workers were killed, including one by police bayonet. Although Denham suggests the disturbance at Frome was localised, the police response and the quick arrest of over 100 striking workers was met with solidarity across the island as dock workers also demanded wage increases and went on strike the following week.

Trade Unionism

In response to the ongoing disruption, the Governor ordered the arrest of William Alexander Bustamante. Bustamante had become a leading figure in struggle for worker’s rights. However, his detention, along with his assistant St. William Grant, fuelled further unrest. To relieve the situation, Bustamante and Grant were granted bail and once released, negotiated on behalf of the workers.

Once out of prison, Bustamante formed a trade union with the assistance of Norman Manley. The Bustamante Industrial Trade Union was heavily influenced by Bustamante’s ‘personal magnetism and unbounded egotism’. [ref]William H. Knowles, Trade Union Development and Industrial Relations in the British West Indies (University of California, Berkeley, Institute of Industrial Relations, 1959), 71. [/ref] Bustamante’s charisma and distinctive personality is captured through some records in the archives. Bustamante would go on to form the Jamaica Labour Party in 1943, splitting from Norman Manley (who had formed the People’s National Party in September 1938) and in 1962, he became the first Prime Minister of an independent Jamaica.

A ‘voice’ in the archive: R. S. Peat

During this period of unrest, on 13 June 1938, a letter was sent to the Colonial Office in London detailing the ‘deplorable conditions under which Jamaican labourers are forced to live and work’. Signed by an R. S. Peat, the letter presents some challenges. Firstly, there is little background on R. S. Peat beyond the two letters in CO 137/827/1. The letter’s content doesn’t say much about the writer. We do know he is writing from Aberdeen, Scotland, [ref]R. S Peat’s first letter is also contained in CO 137/827/1 and might suggest that he is of mixed ethnic heritage, “…those of us who are coloured are made to feel in coming to England or Scotland that we are totally inferior.” [/ref] and the letter suggests he was educated. Yet, the letter also offers us an emotive account of the historical context from a unique perspective – something sometimes scarce or difficult to draw out within the archives.

As we hear, R. S. Peat opens the letter saying:

‘It is quite possible that my appeals will be like ‘seeds falling on stony ground’ but I shall have the satisfaction of knowing that I have done my share to help expose the conditions of modern slavery which exists in Jamaica, after all this boast of “British is Best”.’

The writer alludes to the biblical allegory of the sower. In the parable, the seeds that fall on stony ground are like those that receive the Christian message gladly but give up easily when persecution or trouble arrives (Matthew 13: 1–9, 18–23). Here R. S. Peat suggests that his own message might be received well but will not be heard by the government.

The writer also recognises conditions in Jamaica they liken to ‘modern slavery’ and raises the issue of ‘colour prejudice’ experienced by the Black majority. [ref]The 1930 Forced Labour Convention defined forced labour as “all work or service which is exacted from any person under the menace of any penalty and for which the said person has not offered himself voluntarily”. Slavery was prohibited under the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights. [/ref] Exploitative employment practices remained in place on the island after the ending of slavery in 1834 and deepening poverty continued to be experienced by the working classes. [ref]See Hilary McD. Beckles, How Britain underdeveloped the Caribbean (Jamaica: The University of West Indies Press, 2021). [/ref] R. S. Peat points out that life and work in Jamaica for the many did not reflect the rousing colonial assertion that ‘British is Best’.

Arguably the most evocative thread running through R. S Peat’s letter is the way the writer discusses their own British identity and the tenuous position of the wider empire:

‘You may if you wish Sir, regard me as a fanatic or even a lunatic, but I wish to assure you that there are few Britishers more loyal than I am or indeed than any Jamaican is, but we all know what happens when a kingdom becomes divided against itself, and this is fast happening to Britain.’

Again R. S. Peat evokes biblical imagery, suggesting that the Empire, divided as it is, will soon fall. Yet he also affirms his loyalty to Britain (Mark 3:25). He calls out the ‘wicked oppression of black by white’ people on the island. Later in the text he points out that Jamaicans fought on behalf of ‘King and Country’ in the First World War. As they rightly deduce, other British subjects also volunteered in huge numbers during the conflict.

The following years

Life and work continued to be difficult for the majority of Black Jamaicans during war time, and industrial disruption continued during the early 1940s (CO 137/855/11). The Report of the West India Royal Commission (or the Moyne Report), a report into the conditions of the working classes in Jamaica, would not be published until 1945; its findings considered potentially damaging to the war effort. [ref]See The Report of the West India Royal Commission (or the Moyne Report) at the British Library. [/ref] Despite R. S. Peat’s calls for those ‘who have the interest of the labourers at heart’ to be included in future commissions, no West Indians were appointed. Further West Indians were killed by police in uprisings between 1937–1938.

CO 137/827/1 contains other letters with different ideas about how to improve living and working conditions Jamaicans faced, including from Marcus Garvey, as well as statements in support of the workers. [ref]Including letters from the National Peace Council and the Jamaica Progressive League. There is a letter signed by Marcus Garvey, as well as a copy of a letter from Norman Manley. There are also reports of interviews with organisations including the Communist Party of Great Britain.[/ref] Correspondence from the British Empire Union goes as far as to suggest that the disorder in 1938 was sponsored by communist organisations overseas, reflecting the widely held view that Black people were unable organise and fund political action themselves. [ref]The British Empire Union (BEU) was founded in 1916 after changing its name from the Anti German Union, and argued for a paramilitary force to combat socialism. The BEU advocated for the internment and expulsion of Germans from the British Empire at the end of the First World War, together with the establishing of an educational propaganda programme and changes to citizenship law. The BEU’s assertion that communist agents from America and Britain were involved in the strike action in Jamaica in 1938 was investigated by the police. [/ref] It is important to note, however, the thoughts of those directly affected by the actions of the colonial government in Jamaica, specifically the Black majority, are scarce within the record.

Just over three months after this letter was written, war would break out in Europe. R. S. Peat’s prediction that colonial subjects would ‘stand aloof’ would be proven wrong – approximately 16,000 men and women from the British West Indies were recruited and volunteered for the Second World War efforts. [ref]The British army was also supported by groups such as the Chinese Labour Corps.[/ref]

In the following decade, many Jamaicans, some of whom had lived in Britain as part of their training for the army, or to support the war effort in other ways, would return to the ‘mother country’ in search of work. [ref]The National Archives holds passenger lists of ships from beyond Europe and the Mediterranean including the iconic Empire Windrush Passenger List BT 26/1237 which docked at Tilbury in June 1948.[/ref] But economic underdevelopment continued in the Caribbean over the 1930s and 1940s, underpinned by practices which began in the 16th century with the establishment of slavery by European imperial powers. In looking to other forms of cheap labour after the ending of slavery, such as the migration of indentured workers from Asia to the Caribbean, wealth-extraction continued in the region, albeit under a different guise.

Repeated appeals, such as the one from R. S. Peat, did fall like seeds on stony ground. Yet as populations shifted in the post-war period, people from the Caribbean looked to remake their lives elsewhere, some of them in Britain.

Thank you for providing this overview on the economic, political and social difficulties faced by Jamaicans before, during and after the Second World War. It has helped to contextualise the decisions of Jamaicans to migrate in the 1950s. I was surprised to hear that Peats used the term ‘modern slavery’ so many years before its popular representation today. He used it to discuss the legacy of racism and colonialism in the oppression and the continued labour exploitation of Jamaicans. Today the term is often disconnected from this meaning and used to further prevent the movement of Jamaicans and others from the former colonies through tighter border controls. Remembering his words is important so thank you for bringing this to light.