Collections held by The National Archives offer an important opportunity to explore the significant but often ignored contribution of Black people throughout history. One such person was Euan Lucie-Smith (1889-1915), one of the first commissioned officers of African heritage in a British Army regiment and possibly the first Black officer to be killed (in April 1915), before Walter Tull who died in action in March 1918.

Both men served at a time when the manual of military law forbade non-Europeans from becoming combat officers. Walter Tull is the subject of an earlier National Archives blog for Black History Month, which has been a cornerstone in the schools history curriculum since 1987. Historian Stephen Bourne has also written about the career of Walter Tull during the First World War (see footnote 1).

I first came across Euan Lucie-Smith in an article in The Times on 27 October 2020 entitled ‘Plaque for first black officer rewrites history of First World War’ that said that the memorial plaque of Euan Lucie-Smith was to be auctioned in November 2020 in London. Later, I came across another article about him in the Old Eastbournian produced by Eastbourne College, where Lucie-Smith studied for a year (footnote 2). I also checked the Commonwealth War Graves Commission website which gave details of his commemoration at Ypres (Menin Gate) (footnote 3).

Euan Lucie-Smith was born in Jamaica in 1889. His father was the ‘Honorable’ John Barkley Lucie-Smith, the Postmaster General of Jamaica, and his mother was Lady Catherine Lucie-Smith. He was of mixed heritage. His father was a colonial civil servant born in British Guiana (now Guyana) and his mother was related to the Jamaican lawyer, reformer and politician, Samuel Constantine Burke.

Euan Lucie-Smith was educated in England, at Berkhamsted School from 1901 to 1904 and then Eastbourne College. He joined the Jamaican Artillery Militia in 1911 and is listed as a Lieutenant in a pre-war Forces of the Overseas and Dominions list (footnote 4). At the start of the war in 1914 he was commissioned as a 2nd Lieutenant in the 1st Battalion, Royal Warwickshire Regiment.

However, nothing prepared me for the service record file (WO 339/10918) I retrieved after searching The National Archives catalogue for ‘Euan Lucie-Smith’. It is always an exciting moment when you’re able to examine an original historical document and this was no exception.

This particular War Office series contains records and correspondence about army officers who served in the First World War. The content of these files can vary enormously, from short notes supplying a date of death to a file containing attestation papers, records of service and personal correspondence.

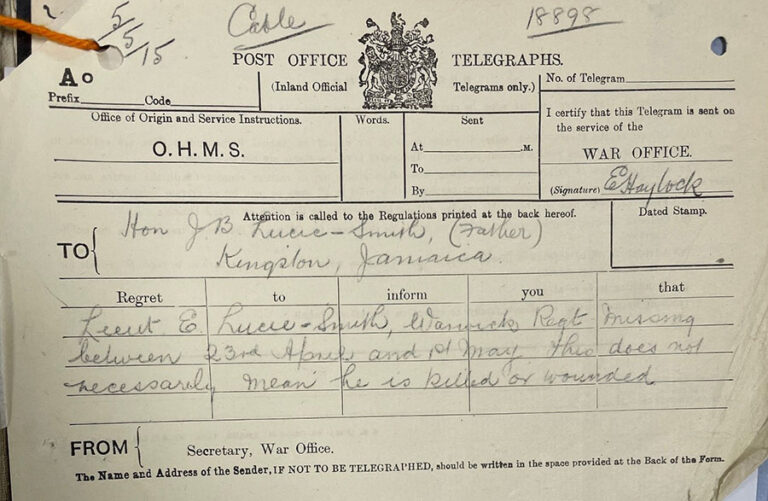

The file on my desk contained material stemming from an enquiry made by the British War Office on behalf of Katie Lucie-Smith about her son, Euan Lucie-Smith, (now Lieutenant) in the Royal Warwickshire Regiment, 1st Battalion who was declared missing in action between 25 April and 1 May 1915.

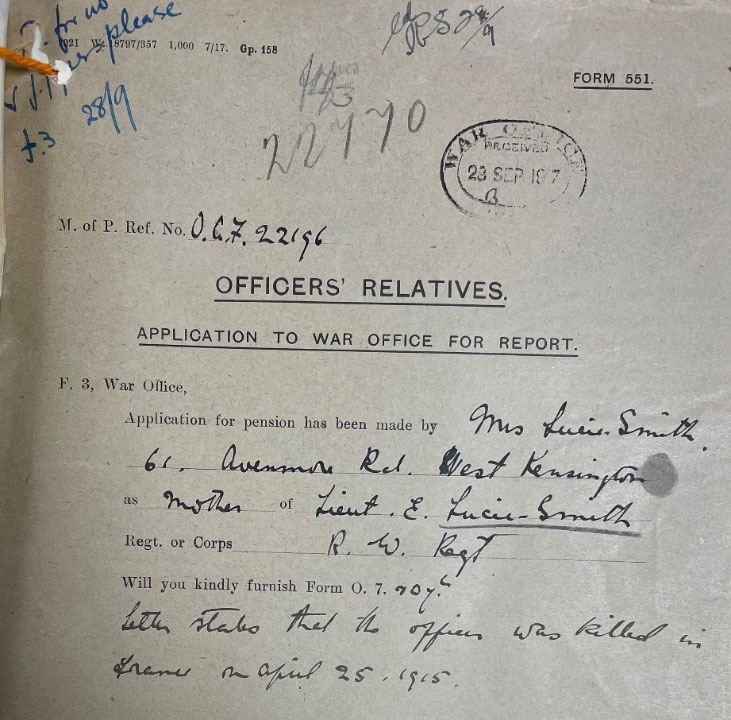

The file starts with a form dated 26 September 1917 entitled ‘Officers Relatives: Application to the War Office for report’. The form has been completed by Mrs Lucie-Smith, who was applying to receive the pension of her son Lieutenant E. Lucie-Smith of the Royal Warwickshire Regiment who ‘was killed in France on 25th April, 1915’.

This is followed by a typed letter from the War Office regarding the issue of ‘the plaque and scroll’ dated 9 September 1919, and the form included the address of Mrs Katie Lucie-Smith as ‘the nearest living relative’ where these items were to be sent.

There is also other evidence that the War Office had conducted an enquiry on her behalf into the report that her son was missing.

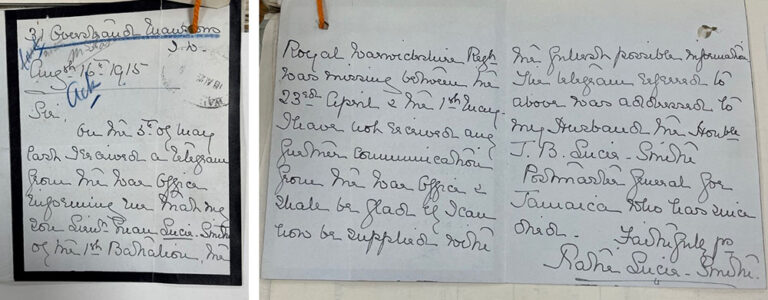

The poignant story of Euan Lucie-Smith is highlighted by the earlier correspondence from his mother found in the file. Her first letter is dated 16 August 1915. She says that she had received a telegram from the War Office informing her that her son was missing and that she had not received any further communication from the War Office. She points out that the telegram (copy shown above) was addressed to her husband, the Honourable J B Lucie-Smith, Postmaster General for Jamaica, who had died.

From the letter we can infer some details about Euan Lucie-Smith’s parents and the social class of the family. His father is described as ‘the Honourable’. He was the Postmaster General for Jamaica, which meant he ran all aspects of the postal service in Jamaica. ‘Katie’ Lucie-Smith has used mourning stationery – we know this because the paper is edged in black, an echo of Victorian times. The style of the letter is formal in tone but reveals a palpable sense of urgency and worry. We know from another letter from Jamaica dated 10 May 1915 from her second son, John Dudley Lucie-Smith that they intended to travel to England in June, which explains the London address.

Another War Office record from the file from 21 February 1916 noted: ‘no further information can be given concerning this officer’s fate. The O.C. (Officer commanding) his Battalion has again been applied to, but is unable to produce further information’.

However, a further letter from Katie Lucie-Smith, dated 7 March 1916 from a different London address, requests information. She says that she has heard nothing about her son despite enquiries, but has ‘lately heard a rumour that there are several unidentified officers suffering from loss of memory and medical trouble caused by the war’. She asks the War Office about the location of these men and the particulars of the ‘engagement her son was on 25th April’. She also asks for details about her other son, ‘2nd Lieutenant J.D. Lucie-Smith who was in France with the Royal Field Artillery, 47th Brigade and had become an officer three months after the death his brother’.

However, in response to this the War Office section concerning casualties say that ‘there are no unidentified officers through loss of memory in our own hospitals, and that no reliable reports that there are any in German hands have so far been received’. It is suggested that she could contact the ‘the Enquiry Department of the British Red Cross’.

A third and final letter from Katie Lucie-Smith, dated 1 May 1917, explains that she had now received information about her son’s death from Lieutenant Miller of the 1st Battalion Royal Warwickshire Regiment now attached to the 52nd Machine Gun Brigade. She understands that he was killed near Ypres on the night of 25 April 1915 and Lieutenant Miller saw her son hit during action. Miller returned to the scene of battle leading the burial party the next day to retrieve the bodies but found no bodies of officers, although several had been killed. And ‘that it was presumed that Germans had removed and buried these officers before the arrival of the British burial party’.

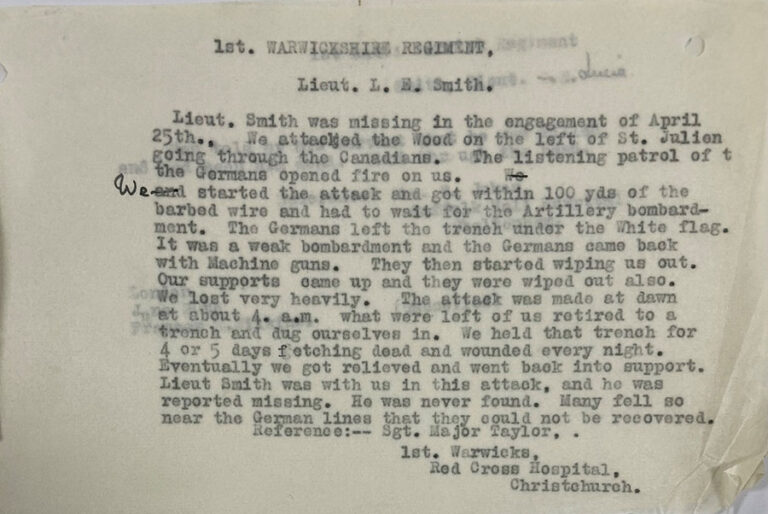

More light is shed on this by a statement from Sergeant Major Taylor of the Royal Warwickshire Regiment, Red Cross Hospital, Christchurch in the file which states that ‘Lieutenant Smith was part of the attack near St Julien and he was reported missing and never found. Many fell so near the German lines that they could not be recovered’.

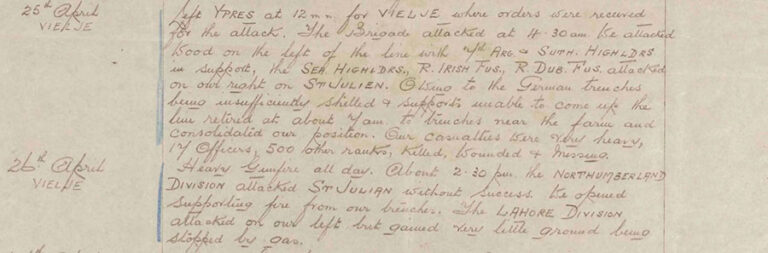

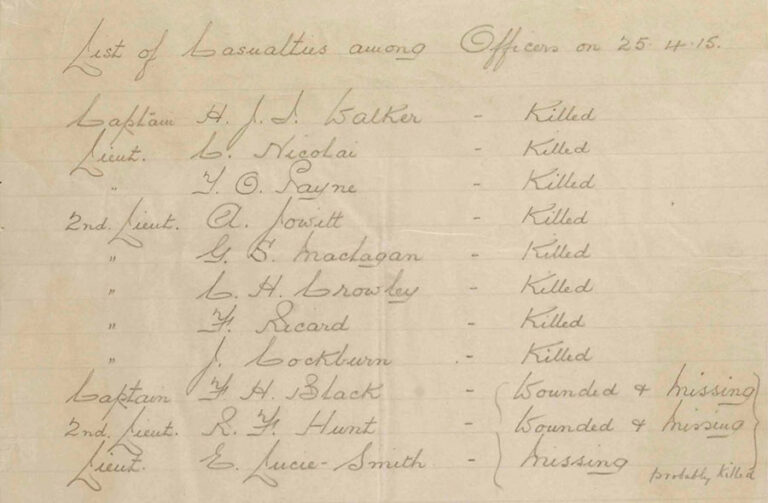

Euan Lucie-Smith was sent to France in March 1915 and tragically died on 25 April that year at the Second Battle of Ypres. We can see from the extract from the War diary for Lucie-Smith (WO 95/14821/2) that the battalion received the order to attack but ‘casualties were very heavy, 17 officers, 500 other ranks killed wounded and missing’. The diary also provides evidence of the role of the Lahore Division at Ypres. Approximately 1.5 Indian colonial troops served in all theatres of the First World War. The effect chlorine gas, which was used for the first time in the war, had is also alluded to in this extract (footnote 5). After this the French and British began to develop gas masks to cope with this deadly weapon of war.

This extract ends with the line: ‘Suggestions: Inadvisable to attack on enemy’s position unless properly supplied by Artillery fire and a thorough reconnaissance beforehand’. The last page for this War Diary for the month of April 1915 includes this page where we can see Euan Lucie-Smith listed as ‘missing probably killed’.

Euan Lucie-Smith is commemorated on the Ploegsteert Memorial in Belgium. Walter Tull is commemorated at the Arras Memorial in the Faubourg d’Amiens Cemetery, Arras, in France. Euan Lucie-Smith’s brother, John Dudley Lucie-Smith, was made Lieutenant in June 1918 and later served in the Second World War. These brave men were significant as they helped to reverse attitudes in the army at the time that Black men were not considered suitable to becoming officers and leaders of men.

Not to take anything away from this very interesting post, shedding as it does light on the experiences of one man of African heritage and those of his mother, but one of the things I am aware of

– as someone who uses the Air 81 series (which details Second World War air force casualties) for personal research – is the heart ache and desperation with which families cling to hope of finding their relative alive.

These files are full of letters where a father, mother or wife has written or spoken to colleagues of their loved one and grasped the tiniest detail or rumour in the face of the evidence to the contrary.

And in a world where bureaucrats are often seen as heartless and uncaring, how civilians and RAF personnel took these scraps and investigated, often for years after the war had ended and there was no other course of action left than to accept the inevitable.

Further to Clare’s comments in her post above, Euan is commemorated on two memorial plaques at Eastbourne College, one in the college’s Memorial Tower and the second in the Chapel.

More information can be found at https://www.iwm.org.uk/memorials/item/memorial/17013 and https://www.iwm.org.uk/memorials/item/memorial/86130 respectively.

Thank you for your interesting blog about Lieutenant Euan Lucie-Smith, his importance in rewriting Black history and the fact that it is also an intensely sad and personal story.

You can find out more about his story and the life of his fellow comrades from the1st Battalion, the Royal Warwickshire Regiment who sadly died on the same day at the Fusilier Museum Warwick.

The Fusilier Museum Warwick bought the unique and nationally significant memorial plaque. It will be on display when the new museum opens at Pageant House, Jury Street, Warwick later in autumn 2022.

For further information see: http://www.warwickfusiliers.co.uk

His name is spelled incorrectly on the plaque. The usual West Indian spelling is Euan, which was his correct name.

It is telling that he lasted about a month, from March until April 1915, and it makes

me question how Much actual training he had as a member of the Jamaican Militia. There were a number of contemporary complaints about commissioning of West Indian militia officers with good family pedigrees but little training. His grandfather was Chief Justice and his great uncle was Governor of the Bahamas.