Please note: This blogpost will use LGBTQ+ as an umbrella term to describe lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer people across a variety of time periods. For more context around the language used in this blogpost, please refer to The National Archives’ research guidance on how to look for records on Sexuality and gender identity history.

LGBTQ+ people often had to hide their sexual orientation and gender identity in order to protect themselves, which led to the purposeful self-erasure of any evidence that could possibly out them. Furthermore, due to the inherent biases of the material compiled by The National Archives, the records primarily present government sectors’ views of non-heterosexual relationships and gender non-conforming people, rather than LGBTQ+ people’s own perspectives on their lives and identities. However, this does not mean that queer lives are absent from government and public records.

The National Archives has records of important legal milestones for LGBTQ+ rights, such as the Wolfenden report which influenced the decision to partially decriminalise male homosexuality in 1967. Famous figures such as Radclyffe Hall (the author of ‘The Well of Loneliness’) and events, such as Oscar Wilde’s trial for ‘gross indecency’, are also well documented. Understanding the everyday lives of less well-known and less affluent LGBTQ+ people is more difficult, but not impossible – though one has to look beyond the documents’ contents in order for LGBTQ+ experiences to be brought to light.

‘The offence of Sodomy is one which presents more variety in the degree of guilt.’ (HO144/243/A35622)

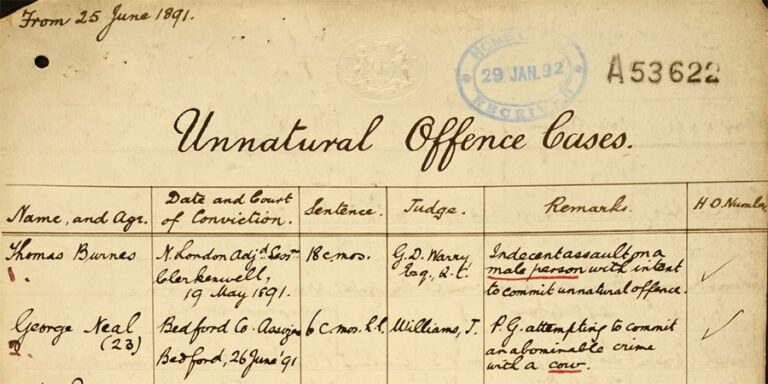

Take, for example, a list of ‘Unnatural Offences’ from 1891 (HO144/243/A35622):

During the creation of the document, ‘sodomy’ and bestiality were categorised as cases of ‘buggery’ and judged to be unnatural offences. The list was drawn up following the Offences Against the Persons Act of 1861, which removed the death penalty for Unnatural Offences[ref]Parliament, ‘Offenses Against the Person Act 1861’, legislation.gov.uk.[/ref]. A letter from 1892, which accompanies and discusses the 1891 list, also mentions the penal servitude act of 1891, which effected the abolishing of the minimum penalty (which was previously 10 years) for those convicted of Unnatural Offences[ref]Parliament, ‘The Penal Servitude Act 1891, 1891 chapter 61’, in legislation.gov.uk.[/ref]. The sentences listed now had the maximum term of 10 years imprisonment. These developments give insight into the slow movement towards the greater acceptance of male homosexuality.

Despite those legal changes, sexual relations between men continued to be stigmatised. They were regarded as a sexual perversion throughout most of British society during the late 19th century, and remained illegal and punishable by imprisonment.

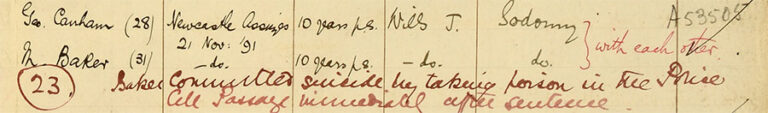

The above picture shows an example from the list of Unnatural Offences from 1891. It records the case of two men, Canham and Baker, who were charged with committing ‘sodomy’ with each other. Their case was one of consensual sex. Nevertheless they were both sentenced to 10 years of imprisonment. Baker later committed suicide after his sentencing.

These documents demonstrate how dangerous it was to live as a gay/non-heterosexual man during the 19th century, and explain the discretion shown by LGBTQ+ lives. However, the archived material also provides evidence that, despite being legally and socially condemned, queer men did exist throughout history.

I heard James say, ‘Why should the Police interfere. They don’t understand us people.’ (MEPO3/758)

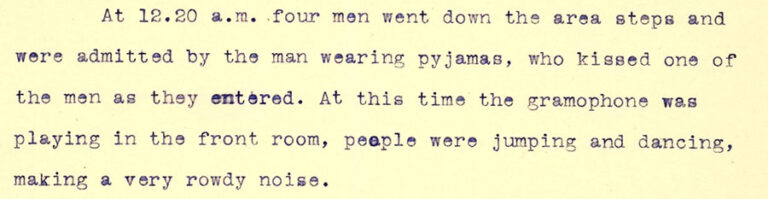

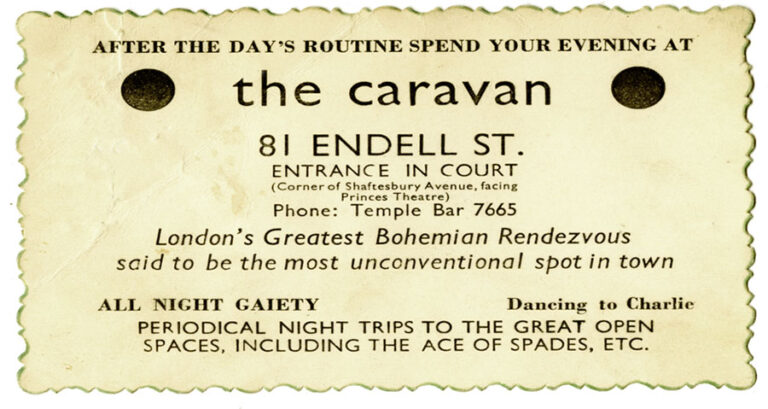

In contrast to life in the time of the 1891 ‘Unnatural Offences’ list, records from the 1920s and 30s show LGBTQ+ lives becoming more varied and detailed, especially regarding LGBTQ+ communities and spaces. The records suggest a greater degree of freedom enjoyed by LGBTQ+ people in London than in the decades beforehand. Police officer statements about LGBTQ+ clubs and the evidence from the raids shed light on the lively nature of such clubs.

The wording used in police and detective statements was purposefully intended to show the scandalous nature of the establishment, and that the proprietors were guilty of crimes such as the keeping of a disorderly house. The statements also focus on the clothes and make-up worn by the men, most likely to emphasise the club’s disreputableness through the perceived ‘deviance’ of its occupants.

The descriptions of the men wearing rouge and calling each other traditionally feminine names, for example ‘Josephine’ (MEPO3/758), demonstrate how those clubs were spaces where people did not need to conform to traditional gender norms.

The statements also mention lesbians and people of colour frequenting places like The Caravan Club. There is less prominence in the records of queer women and trans people, explained perhaps by the fact that sexual relationships between women were not illegal, and that legislation that specifically addressed the rights of trans people would not appear until the 21st century.

Nevertheless, there is a greater visibility of trans people within archived materials after the mid-20th century. There are records documenting discussions among officials relating to transsexuals’ pension age by the late 1950s (PIN 61/27), and records showing cases of those with ‘sex-changes’ registering for retirement pensions before the minimum pension age during the 1970s and 80s (PIN 46/620)[ref]For more information see Dr Louise Chambers recording talk on ‘When a woman is not a woman: How the Ministry of Pensions constructed gender in the 1950s’.[/ref].

‘Air women kissing each other and walking about arm-in-arm would be suspect to most people.’ (AIR2/13859)

Material about the everyday experiences of queer women is limited. However, there are marriage and military records that give insight into their lives. For example, a document dated from 1945-1968 expresses the attitudes of the Women’s Royal Air Force (WRAF) towards same-sex relationships between women.

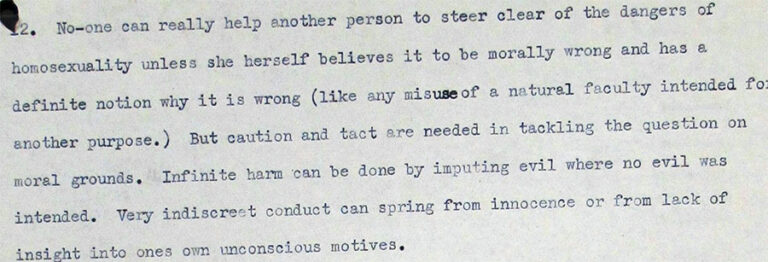

Homosexual relationships between women were not illegal as they were for men. However, this did not mean they were any less stigmatised. The WRAF’s recommended policies on lesbianism suggested that romantic and sexual relationships between women were considered, at the very least, a phase and, at worst, a problem and ‘unnatural’. The document also suggests that being suspected to be a lesbian would have been detrimental to one’s reputation.

Lesbian experiences and relationships in the WRAF likely involved having to exercise discretion and secrecy. The purpose of the policies and procedures document was to prevent and remove homosexuality from within the WRAF. For historians the document provides glimpses into the lives of lesbian women. Regular letter writing and telephone calls between airwomen, for example, were suggested as ways for women to maintain relationships, as physical affection in public was considered suspicious.

Conclusively, despite men and women having to keep their sexual and gender identities mostly hidden to avoid discrimination, LGBTQ+ lives and experiences can be found in the records at The National Archives.

Gillian Gines is a Royal Holloway BA History student in the final year of their degree. Gillian is currently writing their dissertation on the American Civil War. This blog post was written in response to a virtual workshop on LGBTQ+ history in The National Archives collections.

To find out more about LGBTQ+ history in The National Archives records, see our associated blogs and research guidance.

Great blog, Gillian – really enjoyed it! Very well written. Would have liked more discussion on queer women throughout documented history, and why they are so invisible to us. Thank you for writing it.

Thank you Gillian for sharing this with us. Most of us have come a long way in understanding and acceptance but not all. It would have been a terrible time to have to deal with your sexuality and the world being so critical. Having a family member who is only to familiar with the attitudes of others and being Gay now and coming out even in 1970 opened my eyes. One day we will all be equal and it wont be a problem. I have met some wonderful LGBTIQ+ people and wish them all well in the future.

Thank you for this. I understand you don’t include Anne Lister’s diaries – because they are not held by the National Archives. They can be found at West Yorkshire Archives Service, in the collection housed in Halifax Library. Starting in 1806 & ending with her death in 1840, this 4-5 m word journal is partly written in her secret code ~ for obvious reasons. It was belatedly recognized by UNESCO in 2011.