It is safe to say that no lawsuit of modern times has attracted such universal and painful interest. [ref]The Times, 5 June 1918. HO 144/1498/364780. [/ref]

Photograph of Maud Allan dressed as ‘Salome’, 1910. Reference: COPY 1/550/190.

Maud Allan was a much-celebrated dancer on the West End stage in the early 20th century. She captivated audiences all around Europe with her confident and alluring performances. So, how did she become involved in one of the most sensational trials of the 20th century?

It’s a complex tale, involving accusations of treason, a libel case and unabashed female sexuality. This case has been the subject of many historical studies: within queer history circles it is well known. [ref]For example, Lucy Bland, Modern Women on Trial: Sexual Transgression in the Age of the Flapper (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2013); Toni Bentley, Sisters of Salome (Bison Books, 2005); Walkowitz, Judith R. ‘The “Vision of Salome”: Cosmopolitanism and Erotic Dancing in Central London, 1908-1918’. The American Historical Review, vol. 108, no. 2, 2003, pp. 337–376; Philip Hoare, Oscar Wilde’s Last Stand Hardcover (Arcade Publishing, 1998) [/ref] However, this episode remains relatively unknown outside of academic circles, despite the records from the trial being openly accessible at The National Archives.

The wider context of the trial is also particularly relevant. Social attitudes against same-sex relationships, female sexual expression, and foreigners – heightened by public paranoia during the First World War – meant that many people saw those outside of the norms as threats to the security of the nation. As much as being a compelling story in itself, this trial is a window into the tensions and politics of the era.

The performer – Maud Allan

Allan was born Ulla Maude Durrant in Canada in around 1873. In her early 20s she had travelled to Europe to escape her dark family history: her brother had been the culprit behind a shocking double murder in San Francisco. Allan studied piano in Berlin, before taking to the stage as a dancer and impressively turning her fortunes around.

By 1906 she was attracting audiences in Vienna with a version of ‘Salome’, based on Oscar Wilde’s controversial play. Salome was a biblical figure, who was said to have danced before Herod with the head of John the Baptist on a silver plate. In Wilde’s version, Salome kisses John’s severed head, making her the ultimate symbol of a dangerous and lascivious woman. Allan quickly became renowned for her seductive interpretation of the famous Dance of the Seven Veils, for which she made her own revealing costumes. [ref]Lucy Bland, Modern Women on Trial: Sexual Transgression in the Age of the Flapper (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2013), ch. 1. [/ref]

The Palace Theatre (known at the time of this photo in 1891 as the Royal English Opera House), Cambridge Circus, London. Reference: COPY 1/406/467.

This was the first mistake Allan made: playing a sexually confident woman on the stage. The second was being associated with ‘posing sodomite’ Oscar Wilde, whose trial for gross indecency in 1895 lingered within public memory. There were also strict rules at this time about religious depictions on stage, let alone ones as controversial as this.

Allan’s performances toured Europe and beyond, ending up with a very successful run at the Palace Theatre in London from 1908. By 1918 she reprised this role, working with the Dutch theatre impresario J T Grein. [ref]Grein was originally of Dutch origin and had been naturalised as a British subject in 1895 (HO 334/23/8542) [/ref] He had a transformative influence on London’s West End, including founding the Independent Theatre Society, which inventively avoided the censor by holding ‘private’ performances paid for by subscription. [ref]Wearing, J. (2008, January 03). Grein, Jacob Thomas [Jack] (1862–1935), drama critic and impresario. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Ed. Retrieved 12 Feb. 2019, from http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-40461. [/ref]

Grein had his own problematic connections in this era – he had particularly championed works from the continent. He founded the German Theatre in London Programme in 1900, which did him no favours in the anti-German climate of the First World War.

Allan agreed again to the role, this time excited by the prospect of a speaking part. This was not for a public performance, however, but rather a provate, unlicensed one. To be an audience member of Allan’s private performance of Salome, spectators had to apply to a Miss Valettea of 9 Duke Street Adelphi W6. This was a way of escaping the censorship of the Lord Chamberlain, who had banned Oscar Wilde’s works in the aftermath of his trial. [ref]The Lord Chamberlain’s Office had a role in examining and licensing all public plays up until the removal of this role in 1968. Lord Chamberlain’s Office records on plays for this period are held at the British Library. The British Library has the scripts of all new plays performed in Britain from 1824 to 1968, as submitted to the Lord Chamberlain for licensing. [/ref]

The following advertisement was to be found printed in the Sunday Times, on 10 February 1918:

OSCAR WILDE’S SALOME

MAUD ALLAN in private performances by

J. T. GREIN’s INDEPENDENT THEATRE,

April next. [ref]CRIM 4/1398, Central Criminal Court: Indictments. 1918 23 Apr. [/ref]

It was this advertisement that prompted an initial backlash.

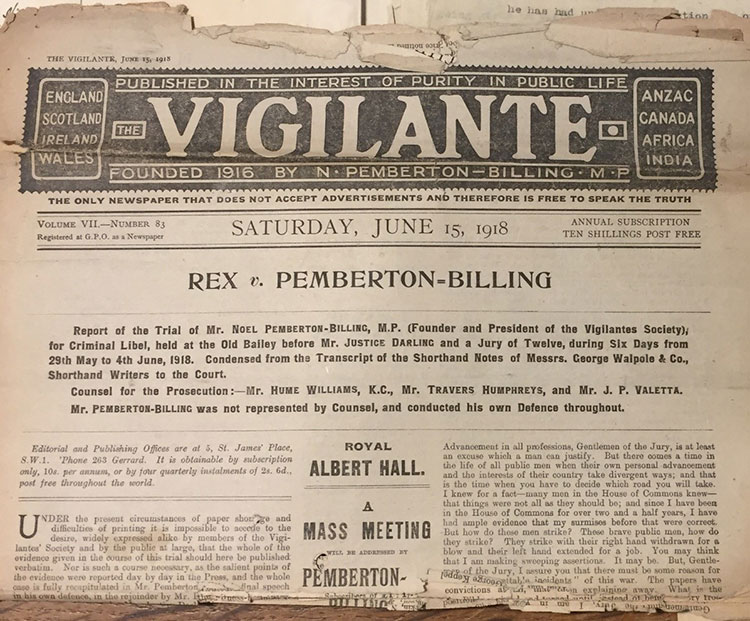

The Member of Parliament – Noel Pemberton-Billing

Noel Pemberton-Billing was a British inventor, writer and Member of Parliament. [ref]The National Archives records document his career with the Royal Naval Air Service and some of his proposed aviation innovations. [/ref] Pemberton-Billing was notoriously right-wing, which was illustrated through his establishment of the Vigilante Society during the First World War. The newspaper of the organisation, ‘The Vigilante’, stated that it was, ‘founded in the interest in purity of public life.’ (HO 45/22797)

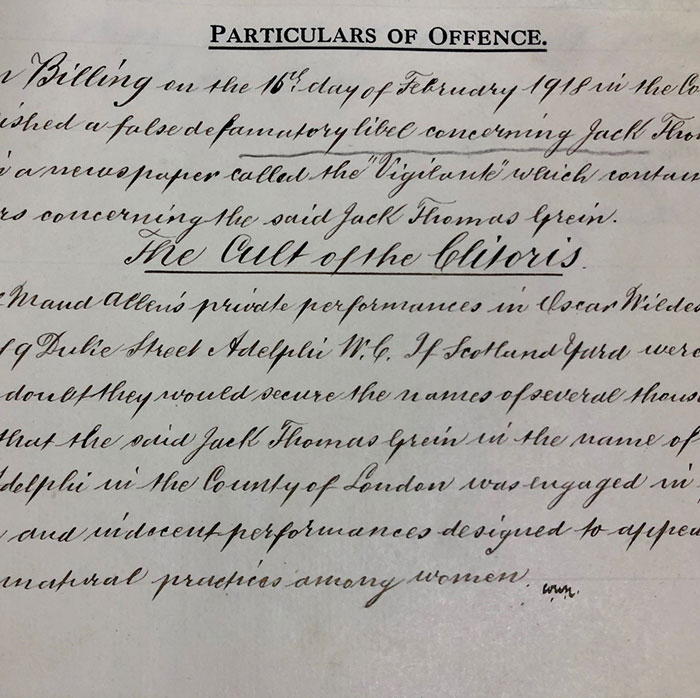

It was in the pages of this newspaper that the allegedly libellous content was published. The paragraph was printed under the sensational headline, ‘The Cult of the Clitoris’.

Extract from the Central Criminal Court Indictments, 1918 23 April. Reference: CRIM 4/1398

Pemberton-Billing used his paper to critique Allan’s upcoming performance in Salome. He essentially implied that Allan was a lesbian, a member of a ‘cult’ of women who loved women. While relationships between women were never illegal, unlike homosexual acts between men, it was nevertheless socially unacceptable and attracted controversy. Even more shockingly, Pemberton-Billing accused Allan of having an affair with Margaret Asquith, the former Prime Minister’s wife.

Photograph of Herbert Asquith, Prime Minister, Mrs Asquith and Miss Elizabeth Asquith, 1910. Reference: COPY 1/552/184.

Pemberton-Billing speculated that Allan’s private performances of Salome would attract a number of high-profile homosexuals, who he believed were named in a ‘Black Book’. The 47,000 individuals said to be included in this Black Book were believed to be being blackmailed by the German government.

The wider context of the trial is particularly relevant. At the height of the First World War, society was looking for scapegoats. As a seemingly-lascivious woman, of foreign descent, who had studied music in Germany, Allan was a logical target. One of the concerns from Pemberton-Billing was that people engaging in same sex relationships would be vulnerable to bribery and, in times of war, he saw this as a weakness to the county. Despite being heavily referenced in the trial, the Black Book has never been found.

These accusations threatened to have a serious effect on Allan’s career. She took Pemberton-Billing to court.

The Trial – The King v Noel Pemberton-Billing

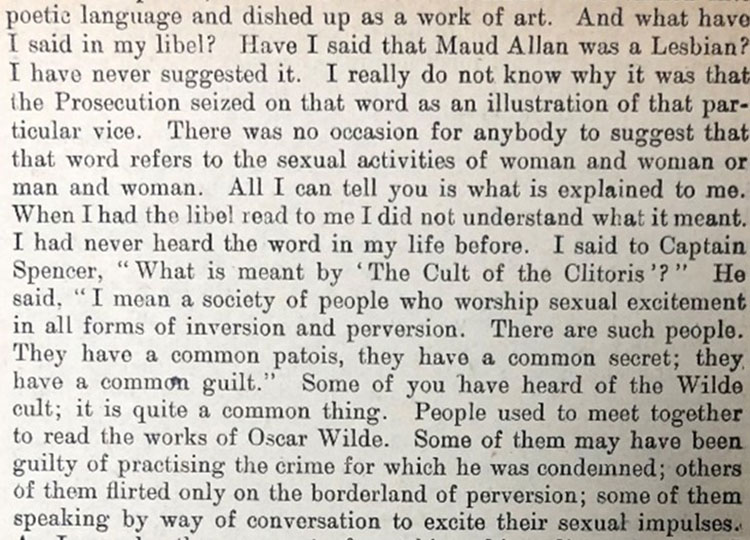

The trial ran over six days. The National Archives holds the associated court records, Home Office files and correspondence around unlicensed plays in his era. One such Home Office file contains correspondence about such private performances (1918-1949, HO 45/22797): in this document is a copy of ‘The Vigilante’ newspaper from June 1918, with a full – albeit biased – report of the trial. This contains Pemberton-Billing’s defence to the accusation of libel. He made the trial even more of a spectacle by defending himself. He claimed that he did not know what the phrase ‘The Cult of the Clitoris’ meant – and the fact that Allan did proved her guilt.

- Calendars of Indictments, 1914 Sept-1922 July. Reference: CRIM 5/10.

When being questioned about the libellous phrase, Allan said: ‘Now, gentlemen, I am not going to soil my tongue with any more description of what those words mean.’ (HO 45/22797) The trial papers describe Wilde as ‘a moral pervert’, with the play further defined as ‘an open representation of degenerate sexual lust, sexual crime, and unnatural passions, and an evil and mischievous travesty of a biblical story.’ (CRIM 4/1398)

Front page of The Vigilante newspaper, June 1918. Reference: HO 45/22797.

Allan, meanwhile, admitted that she knew little about Salome, but (somewhat unwisely) told the court that she regarded Wilde as ‘a great artiste’. (HO 45/22797)

Rather than focusing on the libel accusation, the judge seemed more concerned that the uncensored play had got on the stage at all. In his closing statement the judge noted that the costume Allan wore for her performance, was ‘in fact, …worse than nothing’. (HO 45/22797) Despite being the plaintiff, Allan herself was seemingly on trial.

Home Office papers also picked up on the revelation that Pemberton-Billing’s wife was of part German descent. This is interesting and ironic, in light of his prolific war-time propaganda and feeding of anti-German sentiment. (HO 144/1498/364780)

A section of the report of the trial from The Vigilante newspaper, June 1918. Reference: HO 45/22797

The verdict

Ultimately the jury found Pemberton-Billing not guilty, at which there was said to be a great outburst of cheering in the gallery. In his closing statement, the judge spent a great deal of time detailing how the play was clearly not appropriate for either public or private performances. Salome, Wilde and Allan were publically scrutinised, while Pemberton-Billing had been vindicated.

The wider significance of this can be seen in letters sent to the Home Office and in the Cabinet papers at the time. Speculation in government was evident. What would this trial do to the visibility of lesbianism? Was it counterproductive for Pemberton-Billing, given his conservative nature, to essentially give publicity to a ‘cult’ of women loving women? Reverend Francis Knight wrote to the Home Office during the trial expressing concern. He suggested that it would be wise for the magistrates to dismiss it, ‘rather than give any more publicity to the case – in the interest of this Country and our Allies’, before it was ‘too late’ (HO 144/1498/364780).

Despite Allan’s strenuous denial of Pemberton-Billing’s accusations, it is interesting to note that Margaret Asquith paid for her apartment overlooking Regent’s Park, until Herbert Asquith’s death in the late 1920s. Furthermore, it was in this apartment that Allan lived with Verna Aldrich, her secretary and lover. [ref]Toni Bentley, Sisters of Salome (Bison Books, 2005), p. 82 [/ref]

- Baptist College (previously known as Holford House), Regents Park, London NW, where Allan lived with Verna Aldrich in the West Wing; exterior views of building and grounds. Dated 1937. Reference: CRES 35/3368.

- Letter concerning the lease and maintenance of the much neglected West Wing apartment, where Allan lived with Verna Aldrich. Reference: WORK 16/1192.

At the heart of the case was anxiety about lesbian relationships and the profile that this trial might give to such relationships between women. In the years after the trial, this is emphasised in Cabinet discussions. In 1921 a bill to criminalise lesbian relationships was passed in the Commons, intended ‘to make gross indecency between females a criminal offence.’ (CAB 24/131/61). The major backlash to the passing of this legislation was the fear that criminalising same-sex relationships between women would lead to greater visibility of lesbians – and, therefore, an increase in their number.

Cases such as Maud Allan’s, and the sensation it caused, had contributed to this heightened fear of the ‘cult of the clitoris’.