The Prize Papers is a vast collection of seized papers and goods from enemy ships captured by the British in wartime, (around 1652–1856). It is being digitised in partnership with Oldenburg University. Un-opened, sealed letters are often found within the Prize Papers collection.

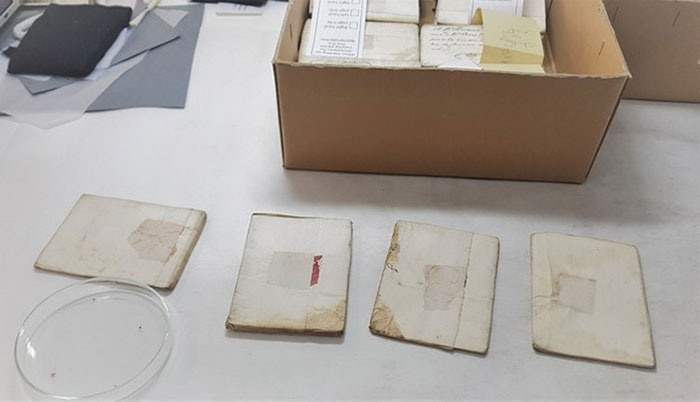

Very few of the closed letters seized in these ship captures, perhaps as little as 5%, have identifying information on the outside – such as the name of the ship that carried them or information on their country of origin. This means that the only way to discover this important information is to open the letters and read them. As a digitisation conservator working on this project, this is what I was asked to do for 200 closed letters so that researchers could determine their provenance.

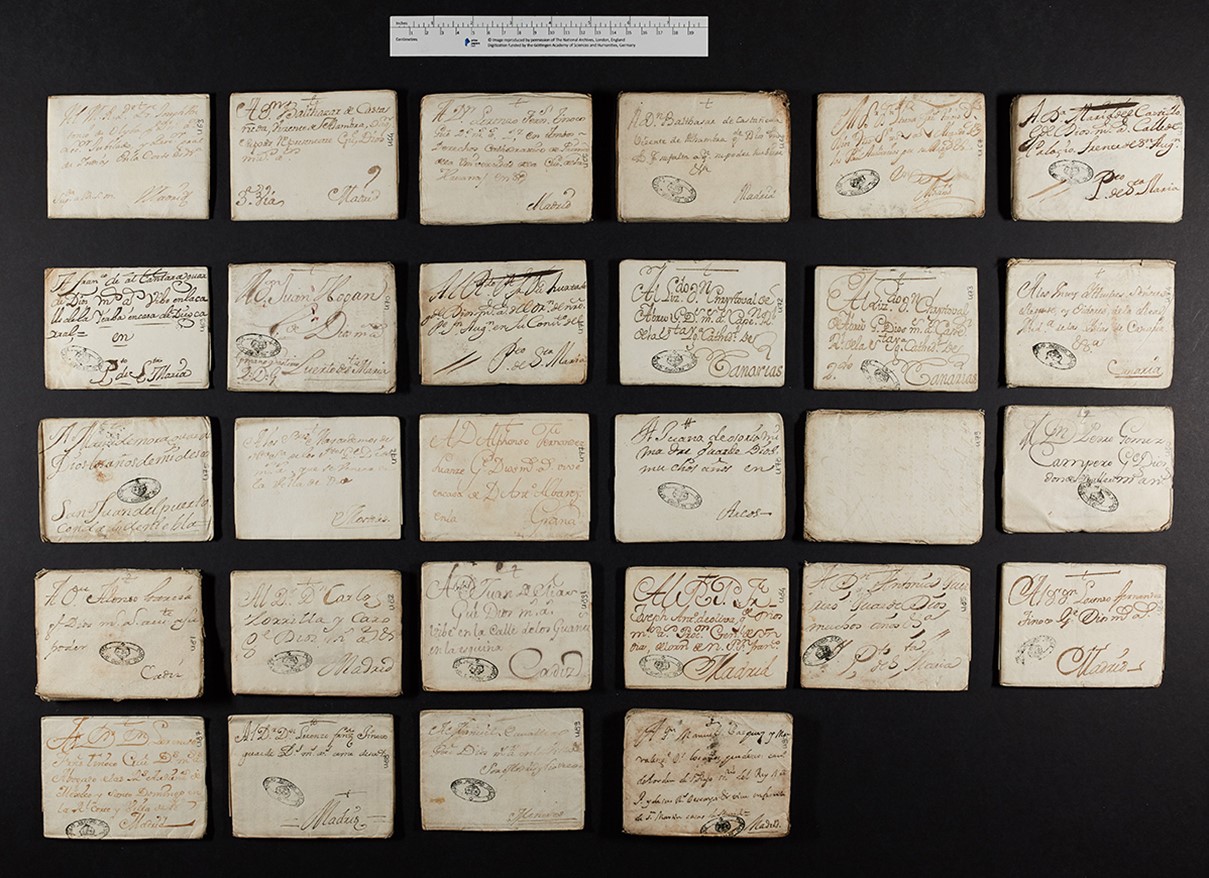

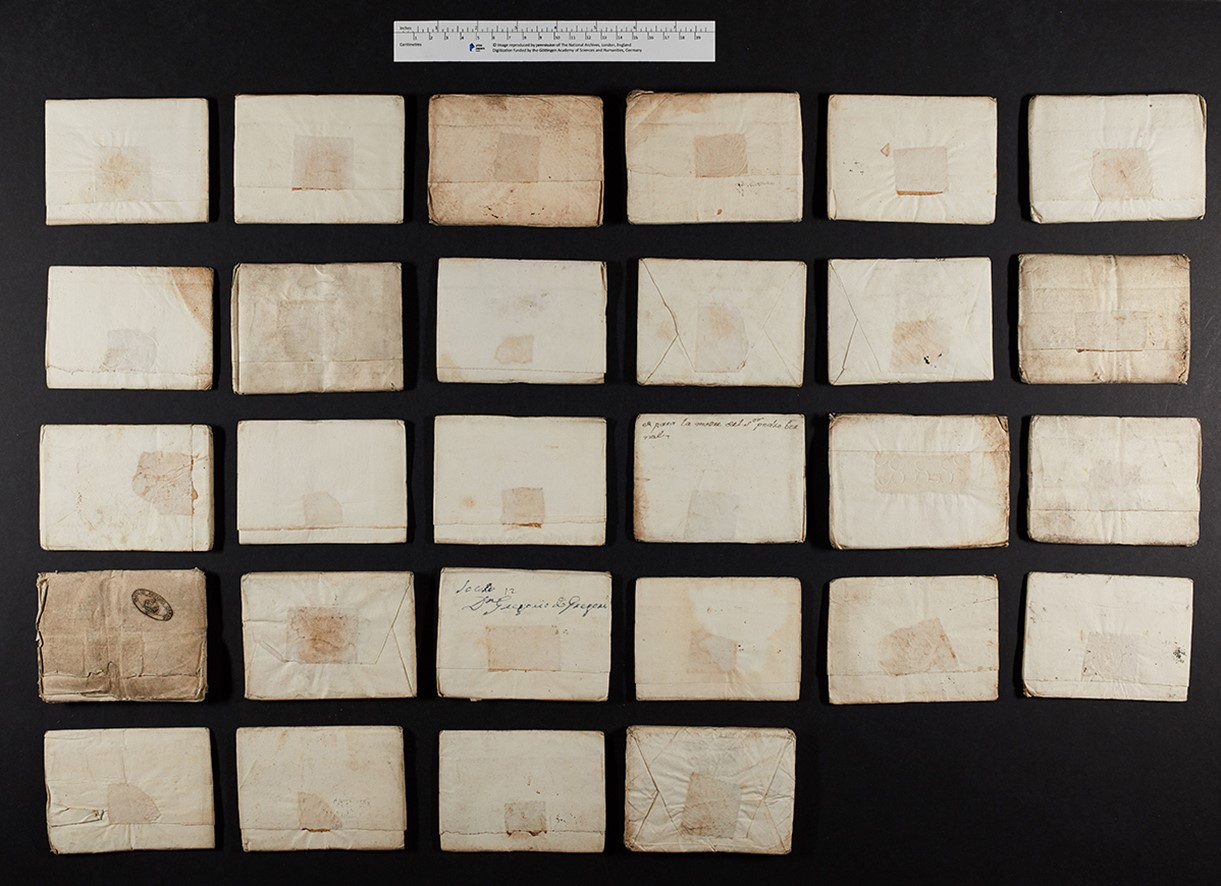

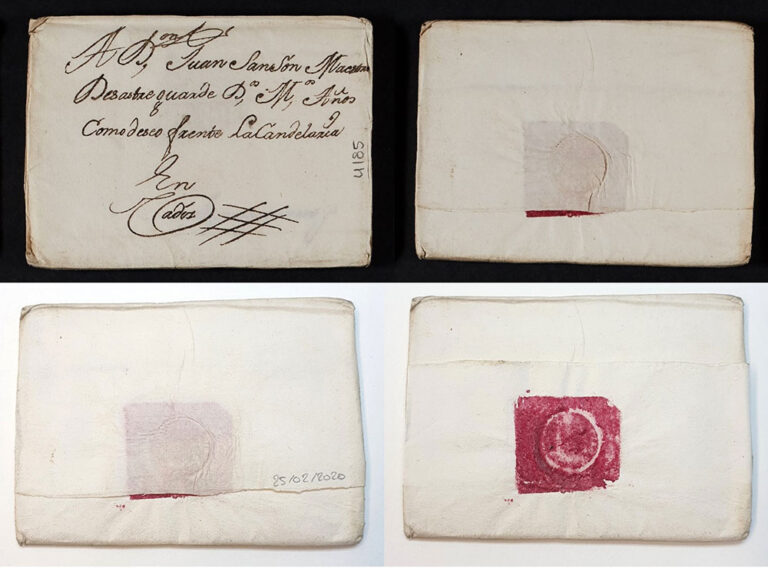

The closed letters I was asked to look at in HCA 32/111E could have come from either the Fort de Nantes, captured in 1747, or the Atrevida, captured in 1779. Photos were taken beforehand to document their appearance. The aim with any treatment to open these letters was to cause minimal alteration to their aesthetics.

Seal Analysis

The closed letters were held shut with seals. I identified three potential groups of seal materials: Shellac seals, brown wafer seals and, pink or red wafer seals. This blog focuses solely on the opening of the wafer seals. Letters with shellac seals were carefully cut open using a scalpel, preserving as much of the physical materiality of both the seal and the letter as possible.

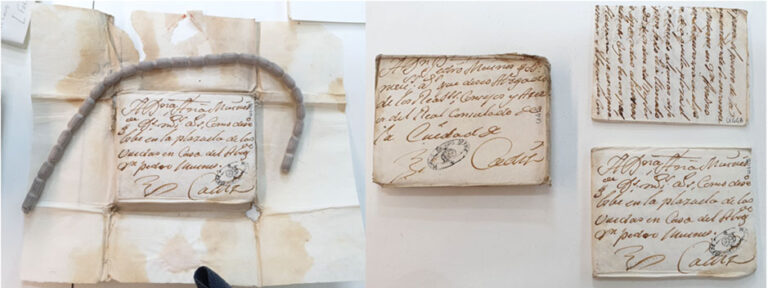

I analysed the seals of four letters using ATR-FTIR spectroscopy. This is a sampling technique that uses the absorption of infrared light to analyse material properties. This test found that, regardless of seal colour, all the wafer seals were starch based.

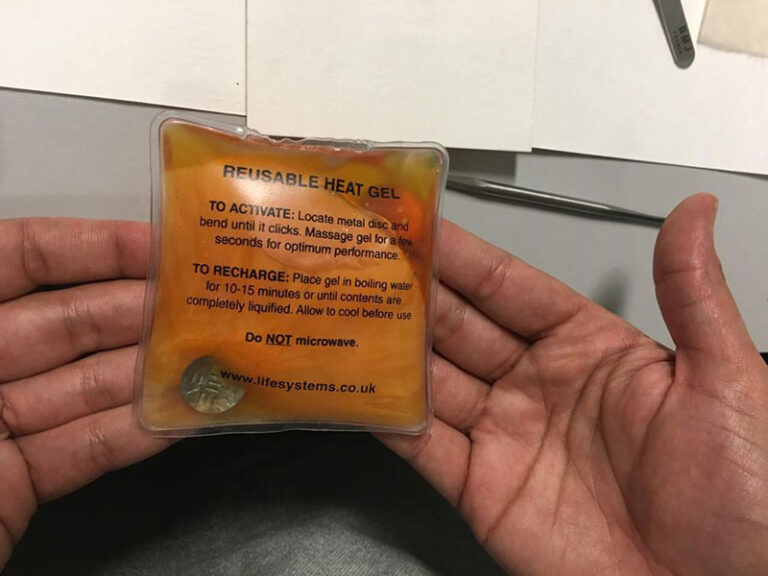

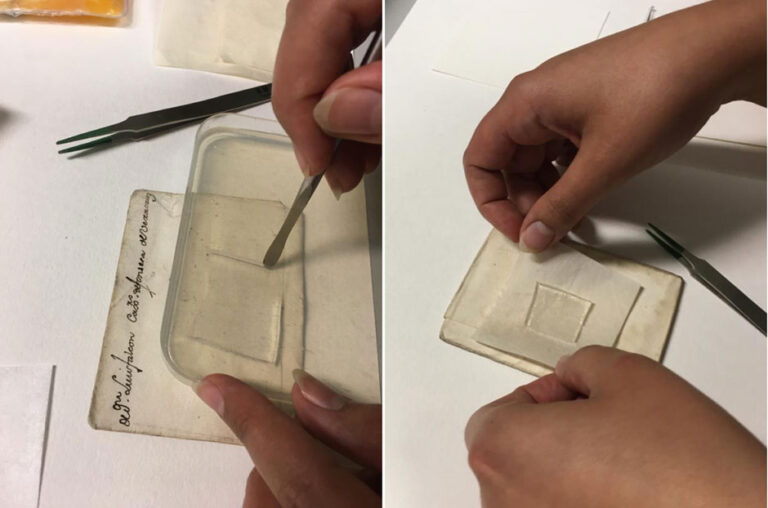

Taking this into consideration, as well as the fact that most of these letters were written in iron gall ink and often had additional letters inside them, I decided the safest way to separate the starch wafer from the letter wrapper was to use an agar gel impregnated with an alpha amylase enzyme. Using a gel allowed me to keep the amount of moisture needed to open the letters to a minimum. This reduced the likelihood of the paper distorting during treatment or tidelines occurring and protected the iron gall ink from possible corrosion.

Treatment

I experimented with different concentrations of the agar gel and alpha amylase enzyme to find a solution that caused as little visible change as possible. The colour and thickness of the seals affected how they reacted to the gel and how quickly they opened, so there were lots of factors to take into consideration.

By using this approach, I was able to open the letters without causing any physical damage, allowing them to be read safely.

Details about the letters can be found in Discovery, our online catalogue.

Just wondering if these letters will be stored flat after digitisation? Whenever I transcribe some of my parchment documents I always endeavour to roll them and store in cardboard tubes. I’d like to find out when printed ‘illumination’ was first introduced on parchment. I have a couple, circa 1749, with George 2nd image on. One document was to do with Oldham Grammar School founded 1611 (from memory) Is there a book with relative info in? I had intended using the chat line for my queries. Cheers. A.

Thank you for your query. After digitisation, these letters will be folded back into their original state and stored in an archival box alongside many other letters. The letters we are working on are made of paper, but if you want to know more about parchment and illuminations, then the following book might be useful: Illuminated Manuscripts, John Bradley.

Utterly fascinating! Thank you for the post

So interesting! I collect (in a small way) seals of the Victorian era and am interested in the making of the paper and ink of the time. With regard to the latter, I believed the following to be true:

“The ‘Indian’ ink of the early nineteenth century was made from lamp black, gum Arabic (or honey or egg white) and distilled water; it was not waterproof. In the latter part of this century waterproof ink was made from oak apples/galls ground to a blue/black powder, gum Arabic and iron2sulphate. The tannic acid therein actually etched the paper and the ink had to be kept in glass or ceramic containers. For red ink, logwood was substituted for the oak galls.”

But you are dealing with letters from the 16th century?

Thank you for your query. The letters that we are working on for The Prize Papers are from 1652–1856, but we do have 16th Century material within the archive.

I believe that in the mid 16th century seals made from shellac mixed with beeswax had only just superseded those of resin and beeswax – with the benefit of making the sealing medium more ‘tamper evident’ if it was disturbed.

As well as alum or gelatin, I believe starch was commonly used as a sizing agent in papermaking during the 16th century when paper was made from pulped cotton or linen fibres. How was starch particularly employed as a material for creating seals for securing letters? Were (paper?) seals made with a particularly high starch content to act as an adhesive when moistened? In the 19th century, a hidden (moistened) circular wafer seal made from dough was sometimes placed under the folded edge of a letter sheet to secure it as an alternative to a visible adhesive paper or wax seal.

Thank you for your query, for The Prize Papers we are looking at letters from 1652–1856. The particular letters shown within this blog are from the 18th Century. Wafer seal were made by combining flour, gum Arabic, water, and a pigment; cooking the thin cakes; and stamping out the individual seals. Another blog on seals by The National archives, U.S might be of interest

Very informative insight into the work you do. Thank you. Keep up the brilliant work.

A completely unimagined field of research. Fascinating.

so interesting! I can’t wait to be able to read some of them. Hopefully the Archives will publish some of these??

Do You have a speaker we could ask to do a talk to our local history society (Barnes)?

Dear Marion,

Thank you for your comment.

To ask questions like this, please use our live chat or online form.