Part one: Conservation for digitisation

Digitisation improves access to The National Archives’ rich collections. It is vital for opening up the nation’s history to new audiences, increasing engagement with collections, as well as ensuring their long-term preservation.

The Conservation for Digitisation team at The National Archives plays an integral role working ‘behind-the-scenes’, surveying and treating documents to ensure that collection material is stable enough to go through the image capture process. To mitigate the risk of damage and to achieve the best image possible, we provide handling guidance to the photographers and are on hand to offer our expertise throughout the image capture process.

The Prize Papers

I started the second part of the internship at The National Archives in June 2019. One of the main digitisation projects I have been working on is called the Prize Papers. This is a unique, 20-year project organised in partnership with the University of Oldenburg to sort, conserve, digitise and create online access to High Court Admiralty (HCA) papers.

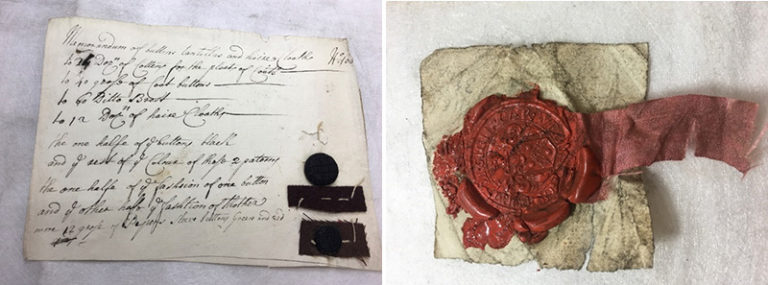

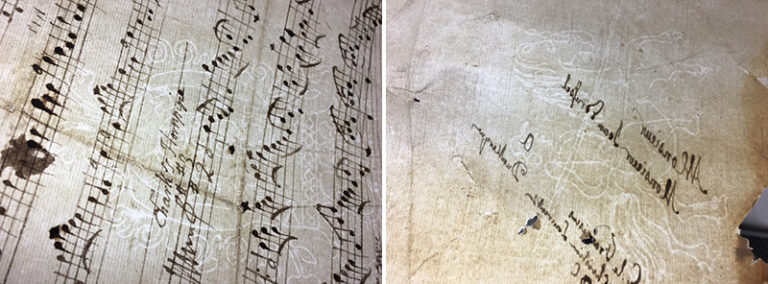

The High Court Admiralty was the court in Great Britain responsible for establishing the lawfulness of naval captures during wartime. A ship’s entire cargo and correspondence were seized as ‘Prize Papers’, and they contain a vast array of material, including fabric swatches and buttons, personal notebooks, ship inventories and trade records.

Project workflow

As this digitisation project is international in scale it has a complex workflow. This begins with the sorting team, who are part of the Collections, Expertise and Engagement department at The National Archives. They order and number the documents. This information is used to facilitate the creation of research-orientated metadata by the Oldenburg project team after the documents have been digitised.

After sorting, boxes are passed to conservation where they are prepared for image capture. Any conservation treatment such as cleaning, paper repair and re-housing is undertaken alongside the recording of the collection’s materiality.

Accurate and meticulous documentation is vital at every stage of the workflow. The conservators are responsible for documenting important physical features such as bindings, seals, watermarks, merchant marks and any evidence of letter-locking. Letter-locking dates to the 13th century and is the method of folding and securing personal correspondence. Levels of security can be created using different folds and then the letter can be secured further with seals. Preserving the folding lines or patterns of dirt and damage is therefore important. This data is input into the project database to provide guidance for the imaging teams, and it will also contribute to future research endeavours.

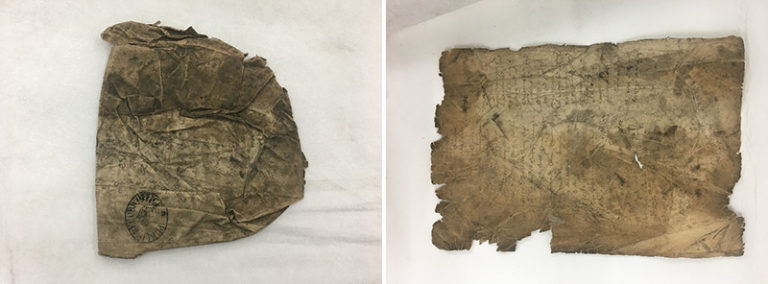

Part two: Treatment of a letter

There are around 100,000 undelivered letters containing personal correspondence within the collection, dating mostly from 1664 to 1817. The letter below represents how vital a conservator’s role is within the end-to-end digitisation process. It was ingrained with dirt, and the paper was heavily distorted, which meant the textual content could not be read.

In order for its provenance to be correctly identified by the sorting team, it required conservation treatment. It was cleaned using a soft brush and chemical sponge, and then any tears and areas of damage were repaired with gelatin re-moistenable tissue. This is a very fine Japanese paper which is pre-coated with adhesive and can then be reactivated with water and applied to the document to repair tears and losses.

The letter is a good example of how the digitisation workflow has to be flexible and is often adapted to the material’s condition. If a document is in a poor condition, perhaps from pests or exposure to moisture (these documents have been at sea after all!), it will be treated by the conservators to enable it to be handled and read. A workflow tracker and shared project database makes the process clear and efficient.

Repairing pest damage

Conservation for digitisation is typically minimal, with treatment focused primarily on the handling areas and repairs done to areas of damage that are most at risk during image capture. However, in this case a full lining with Japanese repair paper was needed to stabilise the letter, which had suffered at the hands of hungry pests. It is now stable and can be handled safely by the photographers and the letters within made accessible.

It has been fascinating and incredibly rewarding to work on such an interdisciplinary and trailblazing digitisation project, which illustrates what can be achieved through collaborative working and a shared vision. I think it highlights well the interlinked nature of research, cataloguing, conservation and digitisation at The National Archives.

Thank you to the Prize Paper Project team and to everyone who I have worked with, across all digitisation projects and departments, as part of my internship! I look forward to the final part of my Conservation for Digitisation journey at The Bodleian Library in Oxford.

Emma Skinner is the current Conservation for Digitisation intern, a two-year post finishing in August 2020. The post is funded by the Clothworkers’ Foundation and run in collaboration with The British Library, The National Archives, UK and The Bodleian Library.