Perhaps, like me, you are enjoying the return of light to your life as Spring arrives and brings with it more hours of daylight. Every year, it always takes me by surprise how much I miss arriving and leaving work during daylight hours during the winter months.

Thinking about light and lighting is one of the aspects of my role here at The National Archives. As one of the 10 agents of deterioration, light is something that anyone concerned with conservation and preservation needs to keep an eye on. To keep the explanation simple, light causes damage by instigating chemical changes in materials. You only have to think of the faded colours of something that has been left out in the sun to get an idea of what I am talking about.

The amount of damage depends on many factors, including the material the item is made of, the type of light or lamp (lightbulb), how bright the light is and the length of time the item is exposed to light. Each time you expose an item to light, some damage occurs, even if you can’t tell by looking at it. This damage builds up over time and once it has happened it cannot be reversed.

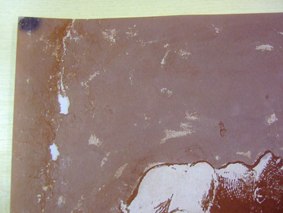

Here’s an example: this facsimile of an artwork by Mervyn Peake was on display for six months – the black dots in the corners and along the edges are where the digital print was covered by magnets and show the original colour. Digital prints can be some of the most stable or some of the most vulnerable items to light depending on the quality of the materials used. In this case, the  exposure to light for a long period has greatly altered the appearance of the print.

exposure to light for a long period has greatly altered the appearance of the print.

Honestly, it would be best for our documents if we left them in their boxes in the dark! However, given that access to the records forms the core of what do, leaving them in boxes in the dark is not a viable option in most cases. So, what then is the other option?

Generally, our records get exposed to light during two very different activities: consultation in the reading rooms and exhibition.

Recently I’ve been involved in developing The National Archives’ new lighting policy for documents on display in our own museum or going out on loan to other institutions. (Yes, we loan our documents for exhibitions at other museums!) We’ve opted to focus our current efforts on a policy for exhibitions as these require our records to be exposed to light for extended periods of time. Previous to this policy, which came into effect at the start of 2012, our aim was simply to keep light levels low and restrict the length of time documents were on display. This is a widely accepted practice within the museum world, but while this approach protected documents, it did not take into account the range in sensitivity of materials to light, nor that many museum visitors require more than just the bare minimum of light in order to truly appreciate the documents on display.

Keeping in mind our dual commitment to preservation and access, we are now taking a risk-based approach that is found in many standards and guidelines currently in consultation along with the 2004 International Commission on Illumination’s Technical Report 157 – Control of Damage to Museum Objects by Optical Radiation. We’re accepting a certain and known level of damage due to light exposure over a set time period. By doing this, we can provide maximum light exposure limits for different categories of materials. This will mean that some documents from our collection can go on display for longer and possibly under brighter lights than previously. On the other hand, it will also provide better protection for those records that are truly vulnerable to damage from light by restricting their display.

It’s been exciting developing this piece of work and seeing it though to implementation as an integrated part of the loans and museum processes. I’ll be very interested to look back in a couple of years to evaluate what impact the policy has made.