The leper hospital of Maiden Bradley was founded prior to 1164 by Manasser Biset, a steward of Henry II. Established entirely for leper women, it was situated a mile north of the village of Bradley in south-west Wiltshire. Several charters at The National Archives demonstrate the patronage of the leper hospital by royals and nobility, indicative of its importance. There is also further evidence of the agency of other leper women outside of Maiden Bradley, who made grants and interacted with local nobles to gain further lands and revenues. For Women’s History Month, this post will provide a snapshot into the lives of the women at the leper hospital at Maiden Bradley, and further guidance into locating women in medieval records.

A history of the priory associated with the hospital forms part of the Victoria County History of Wiltshire, and references the establishment of the leper hospital, as well as a brief history. Little work has been conducted on the hospital or the lives of the women who resided there until its closure in the 14th century. Maiden Bradley was by no means unique to medieval England, however its establishment and existence are worthy of some further digging into the records.

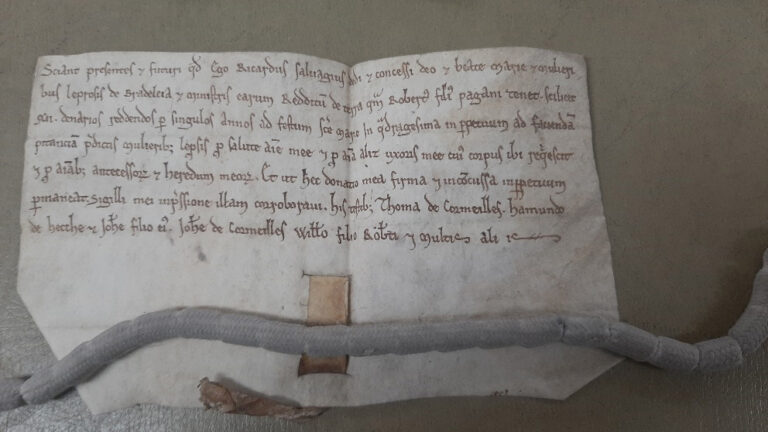

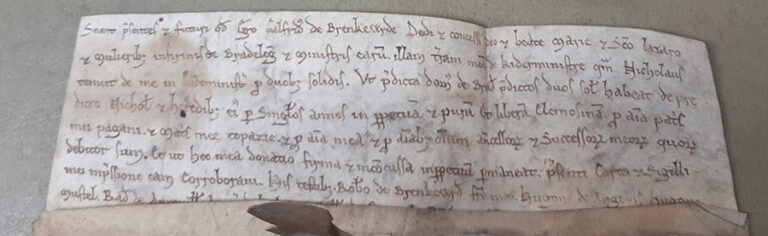

The majority of the records for Maiden Bradley at The National Archives can be located within the E135 and E210 series. Several of the records consist of grants to the women, such as the one displayed above, which is a grant from Richard Savage of a yearly rent to provide for the leper women: ‘scilicet xii denarios reddendos per singulos annos ad festum Sancte Marie in Quadragesima in perpetuum ad faciendam pitanciam predictis mulieribus leprosis’. Other grants dated from the 12th to the 14th century include lands, revenues and indulgences.

Residence in a leper hospital was not undertaken by force: entrance was a voluntary choice, though undoubtedly underpinned by an expectation that sufferers of leprosy would isolate themselves from their original communities. Living in an isolated community could have nurtured friendship among the women, similar to some of the convent communities that developed throughout the Middle Ages. However, without extant letters or further charters from the perspectives of the lepers of Maiden Bradley, it’s difficult to ascertain what notions of friendship may have existed.

As is often the case when researching medieval women, little survives in their own words or as indication of their own agency. It is uncertain whether the grants to the hospital came as part of a request for aid and sustenance by the leper women, or if they were benevolent grants from the issuers in return for prayers for the souls of themselves and their loved ones, or to demonstrate their power and patronage through religious piety.

But how can we uncover women in the medieval records in the first place? There are significant numbers of letters linked with queens (not only of lands that now form Great Britain, but also of wider Europe) and noblewomen, which are more easily searchable in Discovery, our catalogue, and are often located in the Chancery and Special Collections series. To find the histories of women who have no name, such as those residing at Maiden Bradley and other hospitals, searching ‘women’ can bring up records which have been tagged – a task that any keen researcher on Discovery can do. Items in Discovery have varying levels of descriptions, therefore it’s worth taking a chance on a series which may only be described at item level – particularly within Special Collections – and having a peruse of the records either side of the document, as they are often grouped by relevant themes within the volume.

The Special Collections series at The National Archives is a trove for locating marginalised histories, and such is its extent that many of the records have not yet been made more widely known. Although many of the documents relate to elite women, there are several examples, particularly in SC1, SC2, and SC8, which provide documents regarding the activities and lives of lower-class women in the medieval period.

Additionally, there are several useful finding aids at The National Archives in the Map Room which can be used by readers to narrow down their searches. The Selden Society volumes contain pleas and highlight court cases of interest from the medieval period. There are also calendars for the majority of the different financial rolls, namely the Charter, Fine, Liberate, Patent and Pipe Rolls, which are all ways in to the primary sources and contain a vast range of material which can further assist uncovering women’s financial and political activities. Some of these are also available online through the Hathi Trust and British History Online. In addition, the Ancient Deeds series, the printed catalogues for The National Archives, and other finding aids such as the Calendars of State Papers can also be utilised as a starting point for locating hidden histories.

Whether a queen, a noble, a trader, or a leper, women’s histories need to highlighted further and explored. Utilising the trove of records at The National Archives, we can continue to bring these hidden lives to the fore and give agency and a voice to the nameless, such as those who resided at Maiden Bradley.

The leprosy hospital in Bradley was founded for Manasser Biset’s wife Alice. Camden and Leland are clearly wrong when saying that it was founded for Margaret Biset as she was still in her mother’s womb in 1158. Manasser founded other hospitals for those with Hansen’s disease on his land in Doncaster, near Fordingbridge and near the Tower of London; it would seem that he wanted to be near his wife. Margaret retired to the hospital which had become a priory when she was 58 but was called back to court to become nurse to King John’s daughter, Isabella. Margaret treated Isabella as a daughter and reformed the education of royal women. Margaret accompanied Isabella to the harem of Frederick II but was soon recalled to be magistra to Henry III’s young wife Eleanor. When around 80 years old Margaret saved the king from an assassination plot.