To help celebrate National Volunteers’ Week, this blog promotes the work of volunteers at The National Archives

The National Archives holds records of prisoners of war during the Second World War. Our volunteers have recently finished cataloguing the prisoners of war cards in WO 416. They are now cataloguing the reports and interviews, in WO 208, for those who escaped, evaded or were liberated from Germany and Italy. If the prisoner of war was transferred to Germany then a record may be in both records series.

Without our volunteers we could not catalogue these records. Previously the files were arranged by name range or interview number. Thanks to the work of our volunteers researchers can now search by name, bringing history to life.

In this blog Katrina Lidbetter, one of our volunteers, explains some of the work they’ve been able to complete through the cataloguing work around WO 208. Here Katrina looks into individuals escaping from Italy following the Italian armistice of September 1943.

– Keith Mitchell, Volunteers Project Officer, The National Archives

An officers’ prison: Prigione di Guerra

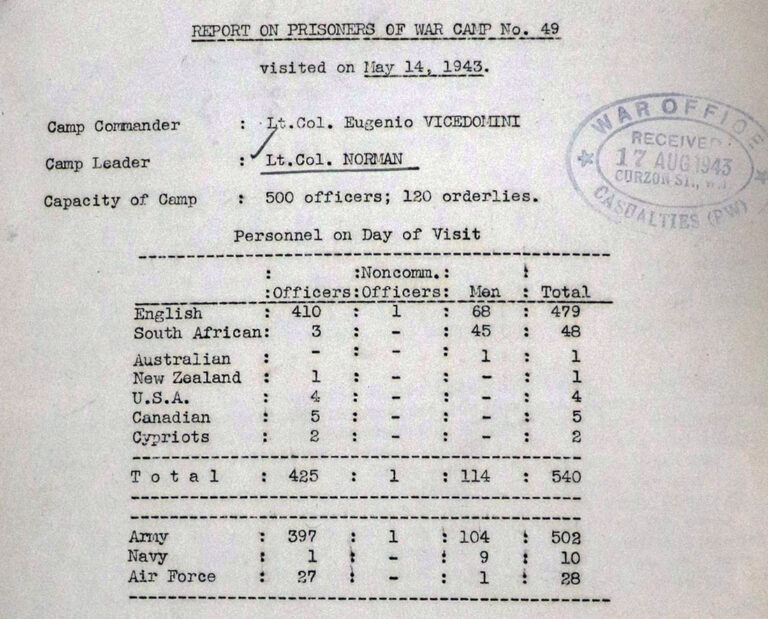

During the Second World War, Italian-run camps in the North Africa and then Italy were grim, with many prisoners of war dying. Only the arrival of Red Cross parcels improved their fate. However, one fortunate camp was Fontanellato, a former orphanage in Northern Italy. An officers’ prison, Prigione di Guerra (PG) 49, held some 500 officers and 100 other ranks. As such, it was better than most Italian camps.

Many of those held at Fontanellato can be found in WO 208. It offers you a glimpse of their experiences. There were many, brave escape attempts – from Fontanellato as from other camps – but very few succeeded in reaching neutral or friendly territory. Escaping was, if anything, harder than from German-held camps. Italy had no foreign labour force that would disguise the presence of a foreigner; the mountains and rivers of Italy presented huge practical challenges; few prisoners of war spoke Italian; and for the locals, an escaping prisoner of war was still the enemy.

Italian armistice

Yet had the escapers known it, there was little need to escape. In 1943, the situation changed. In July, Mussolini was deposed. King Emmanuel appointed Marshall Badoglio to form a new government. Unfortunately, the Germans were quick to exploit the confusion in Italy to strengthen their positions, so that by the time of the formal Italian armistice in early September, the window of opportunity for successful evasion was closing fast – as many evaders were to find out to their cost.

Another factor in the confusion was the British War Office’s instruction to prisoners of war to stay put. By contrast the Badoglio Government instructed camp commanders to let the prisoners of war out, an instruction many camp commanders obeyed, whilst some did not. In Fontanellato, the Italian Commander, Colonello Vicedomini, defied the Germans and released the prisoners of war. For this act he was sent to a German concentration camp.

Fearing they would be shot if caught on the run wearing civilian clothes, many prisoners of war kept their uniform and stayed put in camps or farms where they were working. Of over 80,000 prisoners of war in Italy, thousands were simply rounded up by the Germans and taken to Germany in cattle trucks.

Of those who did get out, many had wildly over-optimistic views as to how quickly the Allies would arrive: a false rumour that the Americans were about to land in Genoa did the rounds. Whilst many did make it to Switzerland or the Allied lines, a number did not, and were instead recaptured, shot, or died of exposure in the mountains.

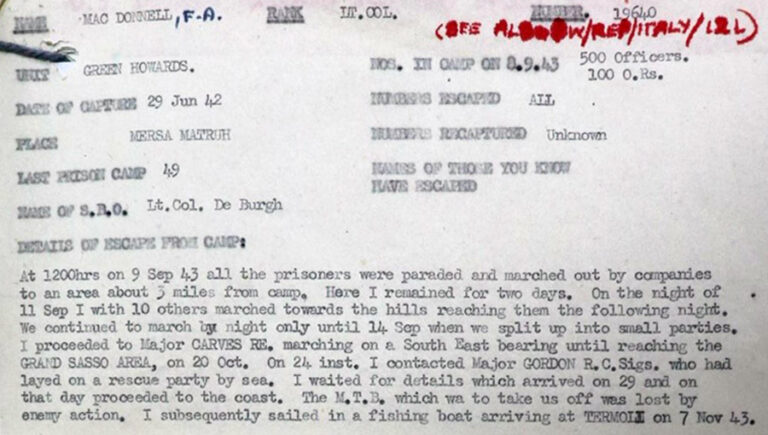

The departure at Fontanellato was led by the Senior British Officer (SBO), Lieutenant Colonel de Burgh. He hid his prisoners of war in nearby woods, obtaining food and clothing from local Italians keen to help. A secret radio gave vital intelligence on the Allies. Vital aid was given by friendly Italian people, who risked their and their families lives in offering food, shelter, civilian clothing, papers, cash and directions to the escaping prisoners of war.

Yet in the end, like all prisoners of war in Italy, they faced the same unpalatable options: a risky journey north to Switzerland, or the even riskier, longer route south to the Allied lines. Any delay was costly, as both the Germans and winter tightened their grip on Italy.

North or south

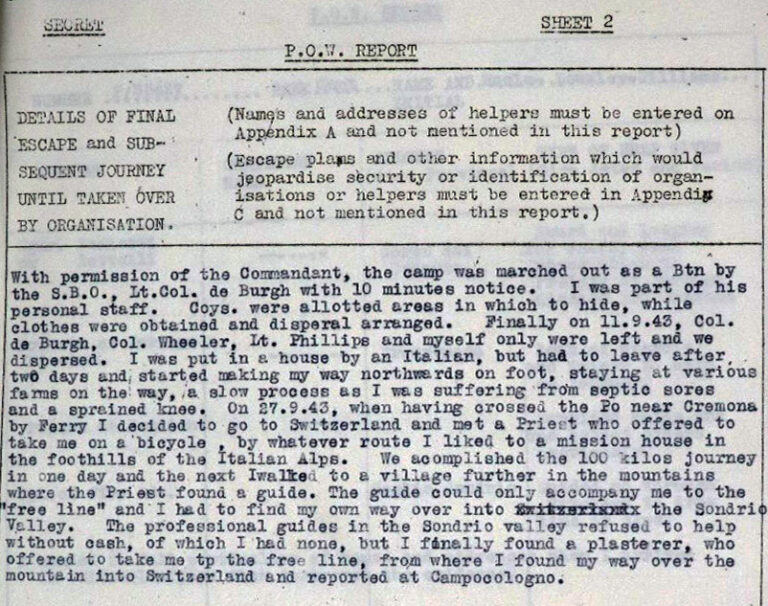

On the SBO’s orders, the prisoners of war split into small groups and headed off. North was the simpler option, but then you would be stranded in Switzerland. Most of those heading to the Swiss border benefited from support from locals, including an active local resistance of men and women. Prisoners of war travelled on foot, by bicycle or with train tickets given to them by local people, sometimes with forged identity cards.

Major Houghton, Indian Army (catalogue ref: WO 208/4255/31), decided it would be simpler to head north as he did not speak Italian. He got from Fontanellato to Engadine in Switzerland in 13 days.

Lieutenant Colonel de Burgh’s predecessor was SBO was Major Hoole Lowsley-Willliams of the 16/15th Lancers (catalogue ref: WO 208/4255/17 and WO 373/64/905). He crossed the River Po to Switzerland.

Lieutenant Derek Francis Hornsby (WO 208/4255/26) headed west, helped by local citizens to hide in the hills near Genoa. He hoped for an Allied landing but eventually gave up and trekked over the mountains to Switzerland.

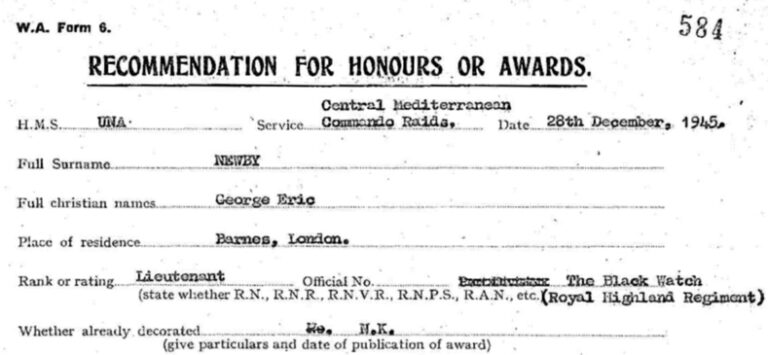

Many others preferred to head south. In Fontanellato’s hospital were Michael Gilbert (catalogue ref: WO WO 208/3317/1684) with an infected boil, and future A Short Walk in the Hindu Kush author Eric Newby (catalogue ref: WO 416/270/230) nursing a broken ankle. Both made it out, Michael on foot and Eric on a pony or mule (Eric was not sure which it was). Eric aided by locals eventually trekked over the Apennines, but was recaptured near the front line and spent the rest of the war in a German prisoner of war camp.

Tony Davies headed south, together with Michael Gilbert and Toby Graham, crossing the mountains and reaching the front line. Tony was wounded, recaptured and sent to Germany. A South African called Hal Becker who had joined them later was shot and killed. Michael and Toby successfully made it over to the Allied lines.

The gloomy, the famous and the earl

Unknown to the Italians and Germans, one of the prisoners of war in Fontanellato was Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery’s stepson, Richard Carver. He volunteered to team up with Lieutenant Colonel Francis Edward Anthony (Tony) Macdonnell of the Green Howards, nicknamed the Gloomy Dean as he resembled the rather gloomy Dean of St Pauls, William Ralph Inge. Tony agreed to say he was only a captain, to attract less attention.

Together they set off on the long trek south. Seeking shelter in a monastery, they encountered the Sixth Earl of Ranfurly, General Neame’s Aide de Camp. Ranfurly had left the Italian ‘Colditz’, Vincigliata Castle, near Florence. Having caught a cold on his trek, Ranfurly was ensconced in a large room with a fire, eating his dinner. To their chagrin, the monastery offered Richard and Tony a small unheated cell for the night. Muttering about the monastery’s fine appreciation of the British aristocracy, nonetheless grateful for any shelter.

Later the two were hidden over winter by a poor Italian family. Both made it to Allied lines: Richard finally made it across in early December 1943. The success of Richard’s old schoolfriend Carol Mather (catalogue ref: WO 208/3316/1543) must have been a bit galling. Carol and another prisoner did not wait for orders from the SBO but walked out of Fontanellato, reaching Montgomery’s HQ on 15 October 1943. They had headed south as fast as possible, getting over the mountains before the onset of winter and before the Germans had fully reinforced their lines. Upon Richard Carver’s return in December, Montgomery’s reaction was ‘Where the hell have you been?’

Find out more

Find out more about Second World War internment and POW records at our free exhibition Great Escapes: Remarkable Second World War Captives. Opening Friday 2 February 2024, Great Escapes explores the human spirit of hope and resilience during times of captivity, revealing both iconic and under-told stories of prisoners of war and civilian internees during the Second World War.

We’ve also scheduled a season of special events to accompany the exhibition that are available to book now.

Further reading

- Eric Newby: Love and War in the Apennines

- Tony Davies: When the Moon Rises

- Tom Carver: Where the Hell have You Been?

- Monte San Martino Trust, commemorating Allied prisoners of war and the Italians who aided their escape.

I know that many Italians were anti-fascist and hid and fed British POWs, including my grandfather. Perhaps a little more nuance in your remark that most locals regarded them as enemy.

Very interesting article though.

Thank you for your comment. Although the Italians were split between those who supported the allies and the Axis forces, without the aid of Italian civilians and military many allied prisoners of war would not have made it back to friendly or neutral ground.

Thanks Katrina. What a wonderful story of derring-do and such bravery and endurance. It’s been a pleasure to read your account.

Many thanks for this work. Is the Italy category still in progress as I do not see it in WO 208?

Thank you for you kind comment. The majority of these questionnaires and forms are now catalogued and available on Discovery. The Italian files are in various places, such as the escapes from Italian Camps, escaped to Switzerland, or general forms. Researchers can search for Name, Regiment or unit, and POW camp. A search for de Burgh in WO 208 finds the Lieutenant Colonel’s report as escaped to Switzerland.

This comment is misleading:

Quote: Yet had the escapers known it, there was little need to escape.

There were very few successful escapes before the Armistice. They can almost be counted on one hand. See my website https://powcampsitaly.webador.com

Janet Kinrade Dethick

Today I discovered that two British Indian Army officers had escaped. They were from 2/3rd Gurkhas, Lt. Col. Charles Edward Gray and Captain Edward Neville Mumford, who had surrendered @ Deir el Shein, when their brigade was overwhelmed by the Afrika Korps. A scroll was created by Captain Mumford whilst in Swiss care in 1944 and lost thereafter till 2022, when it was handed over to the Gurkha Welfare Society in the UK. Then returned to their successor battalion, 2/3rd Gorkhas (an Indian Army unit since 1947).