Among The National Archives’ vast collections can be found the rather overlooked and somewhat forgotten tale of Lady Alice Lisle – regicide’s widow and treasonous dissenter. As part of our ‘Treason’ season, I endeavour to unfold her story.

Alice Lisle, commonly known as Alicia Lisle (or Dame Alice Lisle) was a landed Hampshire lady from the western fringes of the New Forest, who was executed on 2 September 1685 for harbouring fugitives after the defeat of the Monmouth Rebellion. While she personally leaned towards constitutional royalism, she combined this with a notable sympathy for religious dissent. She is the last woman to have been executed by a judicial sentence of beheading in England.

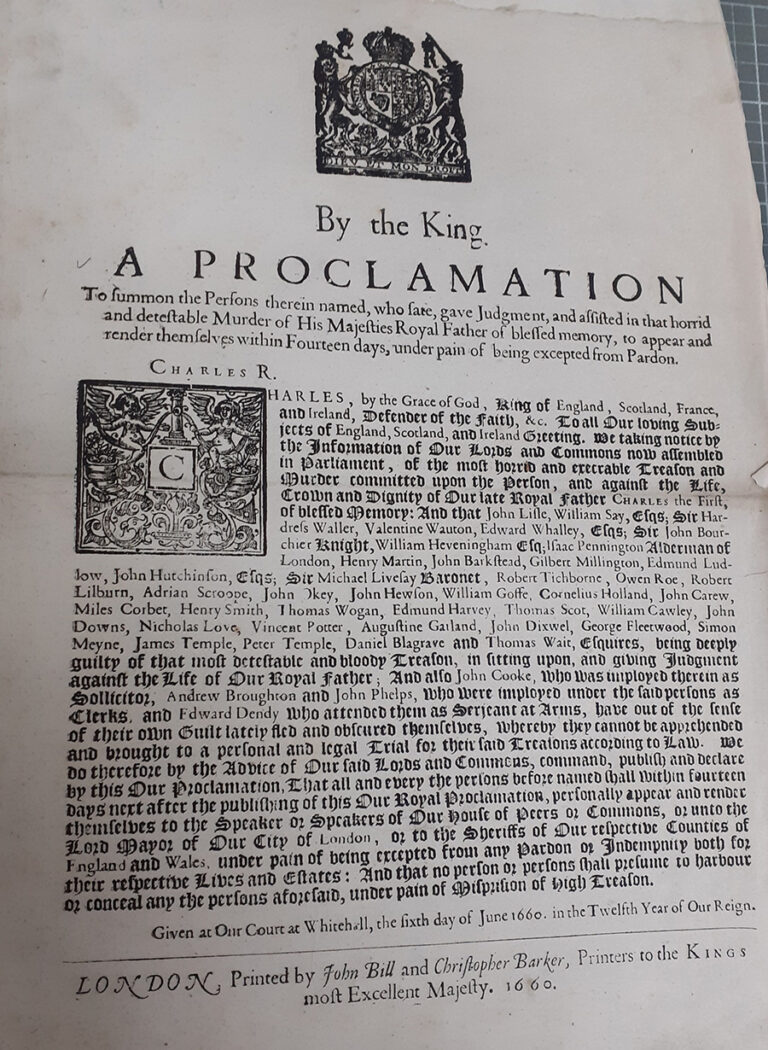

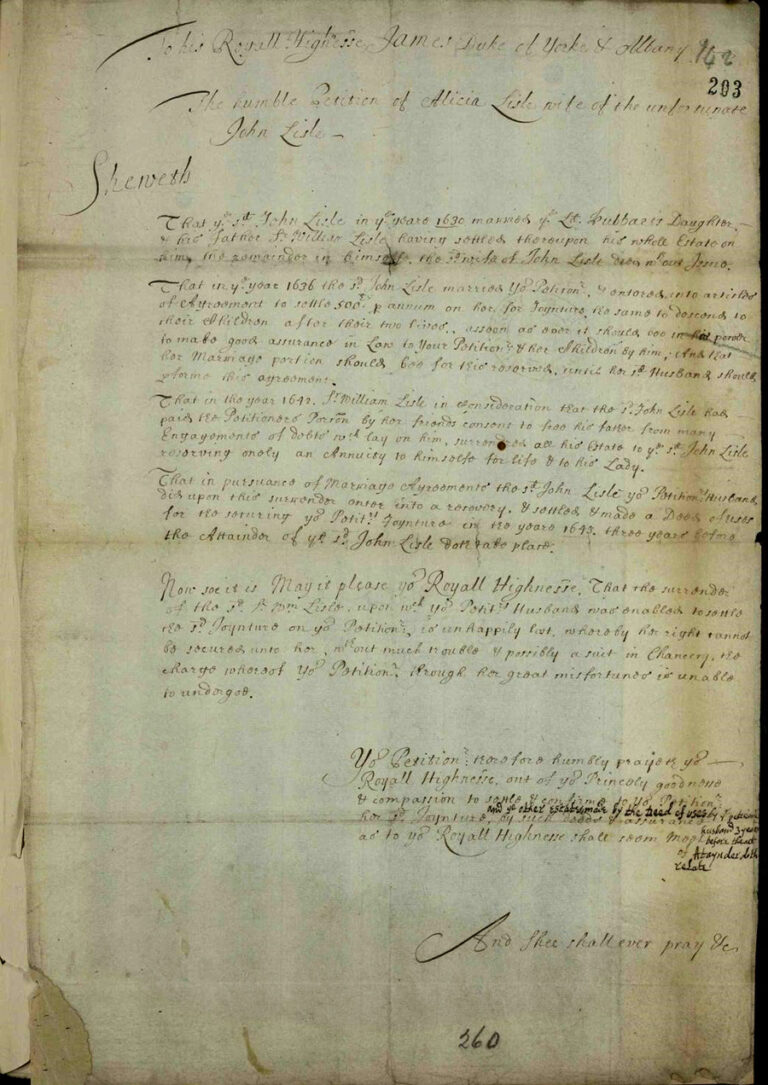

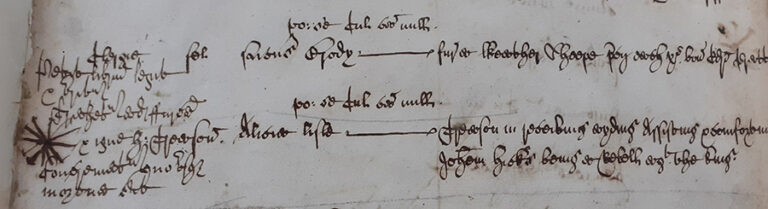

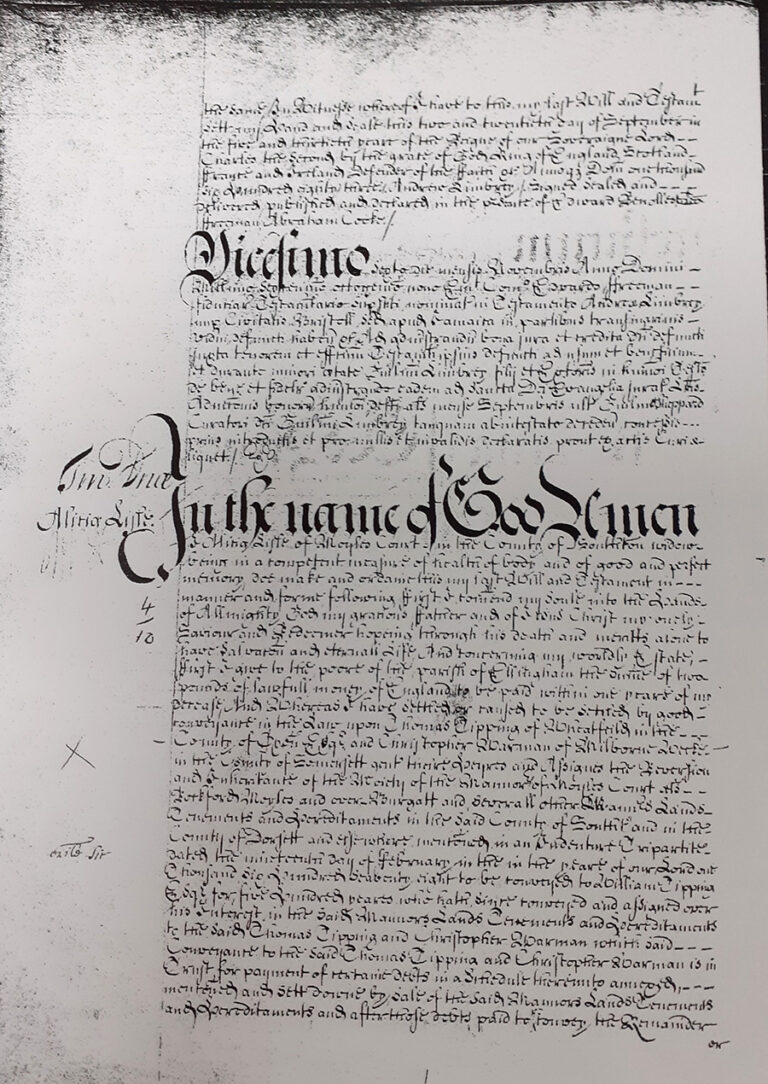

Lady Alice Lisle (née Beaconshaw), supposed traitor, was born at Moyles Court near Ringwood in 1614. In 1636 she became the second wife of John Lisle, an English lawyer who sat in the House of Commons at various times between 1640 and 1659 as MP for Winchester in the Short Parliament, and Southampton in the First Protectorate Parliament. Having supported the parliamentary cause during the Civil Wars, John Lisle, as a member of the Rump Parliament, sat in judgement at the trial of Charles I and was one of the leading regicides responsible for the execution of the king in January 1649.

Alice joined her husband, who had fled to Switzerland after the Restoration of May 1660 in fear of his life as a notorious regicide having been excluded from the general pardon of the Indemnity and Oblivion Act. They eventually settled in the Vaud canton of Vevey on Lake Geneva, and for the next three years lived unobtrusively, moving on whenever he and his fellow émigrés (see footnote 1) felt threatened. Early in 1664 however, John was warned of serious Royalist plans to kill him, and moved to Lausanne (under the anonymous name of Mr Field) where the inhabitants were charmed by his devotion (footnote 2).

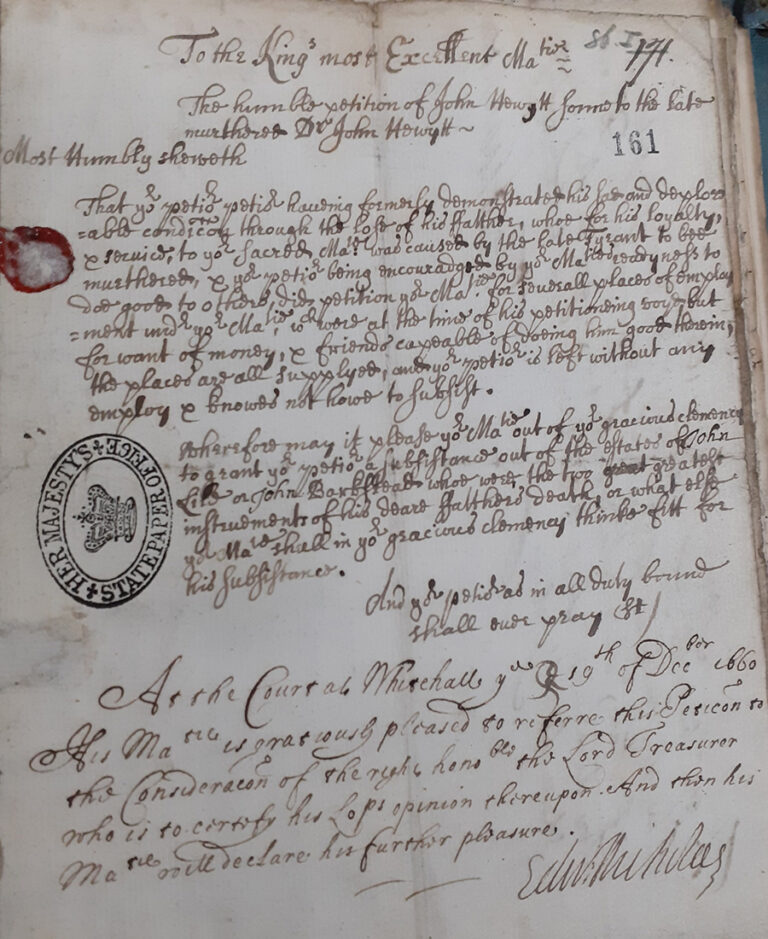

John Lisle’s belief that he was a hunted man proved correct, as he was assassinated in a churchyard at Lausanne by Crown agents of Sir George Downing’s secret service in August 1664 (footnote 3). After the murder of her husband, Alice was eventually permitted to return to England (footnote 4), and settled down at the family seat of Moyles Court, Ellingham which she had inherited from her father. While she was a pious woman who sympathised with Protestant dissenters, she was not an active sectary; indeed Alice had two surviving daughters and a son William, a Royalist, who married the daughter of Lady Katherine Hyde.

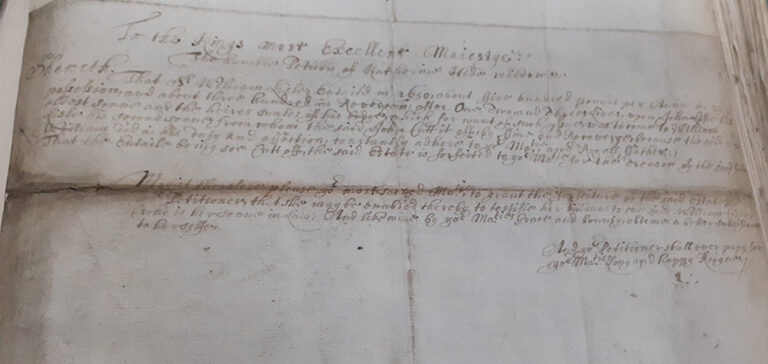

Even before the assassination of John Lisle, there was no shortage of Royalists intent on seizing his forfeited estates. The widowed Anne Duke, for example, wanted both Ellingham Hall and the Abbey lands at Christchurch (footnote 5), while Katherine Hyde asked for Lisle’s income producing assets so she might better subsist for herself.

As a result of these sequestrations (footnote 6), Alice found herself with little more than Moyles Court which was her jointure from her parents, and settled on her before her marriage. Her husband’s death could hardly have left her more isolated – not merely as a widow, aged 47, but as the Cromwellian black sheep of an otherwise committed Royalist family (footnote 7). Her sister’s husband, Sir Thomas Tippins, and John’s younger son Sir William, were both devoted supporters of the Stuart throne.

Alice’s peaceful country life ended abruptly with the landing of the Duke of Monmouth at Lyme Regis and the outbreak of the Western rebellion in June 1685 (footnote 8). A fortnight after the defeat of Monmouth that mid-summer at Sedgemoor outside Bridgewater, Lady Alice agreed to give shelter to John Hickes – a well-known Nonconformist Minister (and chaplain to Monmouth), who had been ejected from Saltash, Cornwall after the Uniformity Act of 1662 (footnote 9), and seemingly unknowingly, also to Richard Nelthorpe, a London lawyer who was under sentence of outlawry (footnote 10). In the ensuing weeks both had fled eastwards as fugitives from the Somerset Levels by way of Salisbury Plain into Hampshire.

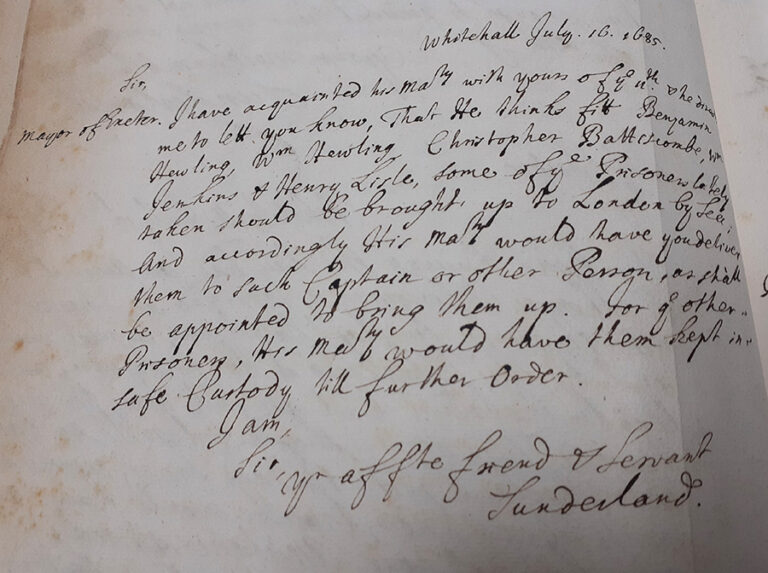

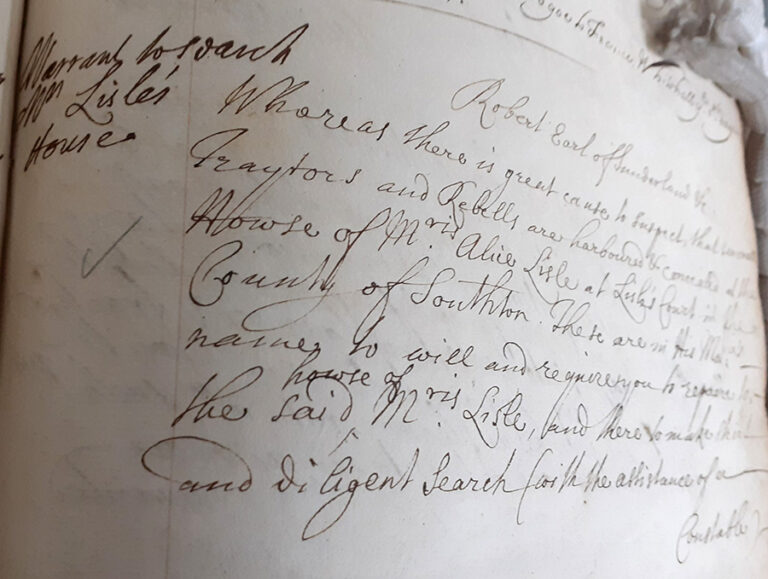

Lisle knew Hickes as a Presbyterian Minister and readily consented to his plea for sanctuary. Alerted by John Barter, a local labourer that the rebels had taken refuge at Moyles Court, orders were issued by the Secretary of State, the Earl of Sunderland, to search the property. Militia under Colonel Thomas Penruddock, Deputy Lieutenant of Wiltshire, arrested Hickes and Nelthorpe, who were hiding out in the brewhouse on 26 July. Lady Alice was consequently also taken into custody, transported to Winchester Castle, and charged under the Treason Act for harbouring Hickes (footnote 11). Ironically, John Lisle had presided at the trial of Penruddock’s father John in 1655, after he had led a rebellion against Oliver Cromwell’s Protectorate (footnote 12).

Brought before a special commission of Oyer and Terminer at Winchester Assizes on 27 August 1685, Lady Lisle was the first person to be tried before the already notorious Lord Chief Justice George Jeffreys (footnote 13) in what was subsequently labelled the ‘Bloody Assizes’ (footnote 14). Dame Alice pleaded she had no knowledge that Hickes’s offence was any more illegal than preaching. Furthermore, she had known nothing of Nelthorpe, who was not apparently named in the indictment, but was nevertheless mentioned to strengthen the prosecution case for the Crown. She stated that she had no sympathy for the Western rebellion, and Monmouth’s conspiracy against James II’s kingship. However, to drive home the serious consequences of harbouring fugitives, the government clearly wished to make an example of the aged Dame Alice (footnote 15), who was now over 70 years old, infirm and nearly deaf.

While she proclaimed her innocence and loyalty to the realm throughout her ordeal, what makes the surviving trial documents of Alice Lisle so controversial is the malicious language and abrupt demeanour attributed to Judge Jeffreys. Its excessiveness is thought to differ from any trial record involving him (footnote 16).

Although there is no actual evidence that Lisle knew either fugitive had rebelled in support of ‘King Monmouth’, a clear ruling from Jeffreys drove the jury to find her guilty. While Jeffreys’ conduct of the trial was markedly heavy-handed, he infamously asserted that ‘he would have found her guilty even if she was his own mother’ (footnote 17), it was the strength of the evidence against Alice that ultimately secured her conviction. Lady Alice acknowledged hiding Hickes but steadfastly rejected the charge of treason; replying directly to Jeffreys, she stated: ‘and I beseech your Lordships believe that I had no intention to harbour him but as a Nonconformist; and that, I was no treason’ (i.e. traitor) (footnote 18).

Jeffreys’ brutal conduct of the six hour trial, which only ended at one o’ clock in the morning (after two adjournments), has come to define him for historical posterity. He showed no pretence or impartiality, becoming a partisan of the prosecution by repeatedly reminding the jury of John Lisle’s role in the trial and execution of Charles I, always with the warning that they should consider it when weighing the question of her guilt. His hostility towards Lady Lisle, who often fell asleep during the proceedings, was clear to all. The jury, after much pressure from Jeffreys, reluctantly found her guilty of high treason after 15 minutes of consultation.

As the law recognised no distinction between principals and accessories in treason, she was initially ordered to be burnt at the stake (footnote 19), but her sentence, after James II had refused to extend mercy to her, was commuted to beheading (as befitted her rank as a gentlewoman) following a petition from her family. In her dying speech (footnote 20) Alice reiterated that her only crime was ‘entertaining a Nonconformist Minister’. She died with great strength of purpose, and expressed joy that she had suffered for an act of charity and piety.

In 1689, following the petitioning of her daughters Tryphenna and Bridget, one of the first acts of the Parliament of William and Mary after the Glorious Revolution was to reverse her attainder on the grounds that the prosecution was extorted by the violent and often illegal practices of ‘Hanging’ Judge Jeffreys. Although Jeffreys did, in fact, adhere to the strict letter of the law of the time.

Popular opinion overwhelmingly supported Alice Lisle, portraying her as a religious martyr – a victim of royal vengeance. Many were shocked that a woman of her age and social standing should be condemned to the block. Several writers have described Lady Lisle’s death sentence as ‘judicial murder’; Bishop Gilbert Burnet, for example, in his influential History of His Own Time (first published in 1724), called her the most important martyr of the Bloody Assizes.

The National Archives’ ‘Treason, People and Power‘ exhibition runs until 6 April 2023.

Footnotes

- Arguably the most important regicide at Vevey was the arch-republican Edmund Ludlow.

- Anthony Whitaker, The Regicide’s Widow: Lady Alice Lisle and the Bloody Assize (Sutton, 2006, p.17).

- Led by the Irish Royalist James Fitz-Edmund Cotter, who became the Jacobite military governor of Cork in 1689.

- Indeed Richard Cromwell himself, who was not accountable for the death of Charles I, returned to England from European exile under the assumed name of John Clarke in 1680.

- Whose husband Robert had taken part in Penruddock’s rising of 1655, and had been sold into slavery in the Indies.

- James, Duke of York acquired John Lisle’s former estates on the Isle of Wight.

- While having an Anglican marriage ceremony, both John and Alice Lisle adhered to wartime ‘political puritanism’.

- The Duke of Argyll led a simultaneous ill-fated insurrection in the Western Highlands, which was markedly better equipped and organised than Monmouth’s. Edward Vallance, The Glorious Revolution: 1688- Britain’s Fight for Liberty (Abacus, 2016, p.53).

- The May parliament of 1662 authorising the use of a revised version of the 1559 Elizabethan Prayer Book.

- Nelthorpe had been implicated in the notorious Rye House Plot of 1683.

- First codified under Edward III in 1352, and extended to Ireland in 1495, and to Scotland in 1708.

- Beheaded at Exeter in May 1655 it was a classic case of levying war under the Statutes of Treasons.

- Condemning many innocent men during Titus Oates’ pretended ‘Popish Plot’ of 1678-1681.

- Jeffreys meted out gruesome punishments of hanging and quartering to some 450 Monmouth rebels, while 850 were sentenced to transportation and indentured servitude in the West Indies. Vallance, The Glorious Revolution (pp 67-68).

- Peter Earle, Monmouth’s Rebels: The Road to Sedgemoor (London, 1977 pp 169-171).

- G W Keeton, Lord Chancellor Jeffreys and the Stuart Cause (London, 1965, p.314).

- C Chenevix Trench, The Western Rising: an account of the rebellion of James Scott, duke of Monmouth (1969, p.237).

- C Bruce ed., The Book of Noble Englishwomen: lives made illustrious by heroism, goodness and great attainments (1875, p.136).

- Elizabeth Gaunt having been falsely implicated in the Rye House Plot was sentenced to death at the Old Bailey in October 1685. Condemned to be burnt at the stake, she was the last woman executed for a political crime.

- Her scaffold speech was heavily embellished by the Whig radical John Tutchin. J G Muddiman ed., Notable English Trials: The Bloody Assizes (London, 1929, p.29).

Interesting and timely. I am just reading the new Robert Harrris’ ‘Act of Oblivion’ about the search for regicides – in particular Whalley and Goffe who fled to America. I believe hang, drawn and quartered was the standard men’s punishment for treason.

I did not know Judge Jeffreys conducted any of the trials though.

Many thanks Peter for your comments, most appreciated.

Infact Jeffreys was too young to have presided at any of the trials of the regicides during the 1660’s (as he only took up a legal career in 1668). However, he sat in judgement of those indicted in both the ‘imagined’ Popish Plot, and the Rye House Plot of 1683.

John and Alice were my 11th great grandparents. Thank you for telling their story- I learned quite a bit from your article and had never seen any of these documents before. Thank you again!

Thank you for your kind words, I’m glad you liked the blog.

John and Alice were my 9th Great-Grandparents and I am just now learning more of their story. Her daughter, Margaret married a Whitaker which is on my mom’s side of the family. I am hoping I can find more stories about John and Alice as well as my other ancestors stories. Thank you for this blog and I wish you much success and more.

John and Alice are also my 9times great grandparents I am also descended from Margaret Whittaker via my dad .

I have been recently tracing my ancestry and I am linked to Sir Thomas Tippin ( Tipping) hes my x10 times great grandfather, and have just stumbled across his Aunt Alice Lisle.

I feel quite humbled, and God rest her soul.