There is a new exhibition on Trailblazers: Women travel writers and the exchange of knowledge at Chawton House, looking at women who travelled the world and wrote about their experiences in print. One of these women is Lady Hester Stanhope.

We have loaned two documents concerning Lady Hester Stanhope to the exhibition, which is open from 12 September until 26 February 2023.

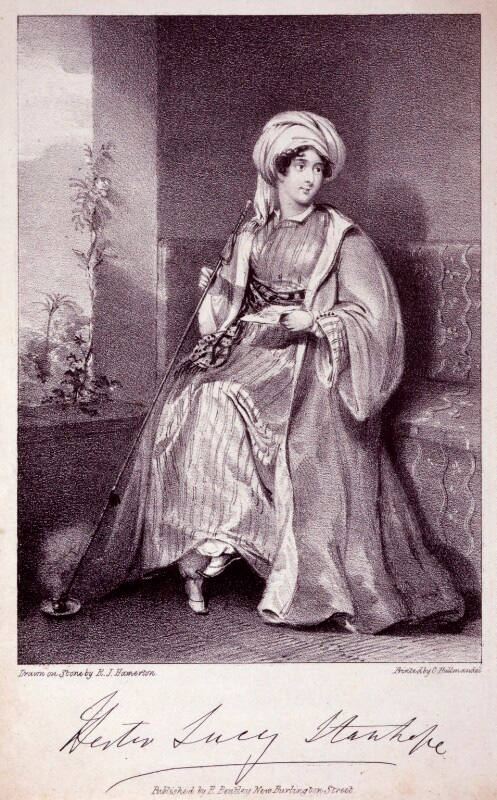

Lady Hester Stanhope was born in 1776. She was the niece of William Pitt the Younger and, in 1803, moved in with her uncle and acted as his hostess for three years – first at Walmer Castle and then at 10 Downing Street when Pitt became prime minister.

Pitt died in 1806, but made provisions for Lady Hester, who was granted a £1,200 pension by George III, in recognition of the services rendered by her family (HO 42/84/1).

In 1810, Lady Hester left Britain. She travelled through France, Italy, Greece, Turkey, Egypt and Syria. She was the first English woman to enter the Great Pyramid. She was shipwrecked in Rhodes, and started dressing as a man. She conducted excavations in Palestine, and she rode through Palmyra. She settled down in Joun, on Mount Lebanon, around 1814. According to newspapers of the time, her influence was considerable – she was the Queen of the Desert, a modern Zenobia, the uncrowned Queen of Lebanon.

There is unfortunately little sense of Lady Hester’s travels, adventures and archaeological endeavours in our records. Apart from a vain attempt by Stratford Canning, the British ambassador in Constantinople, to convince her to leave Turkey in 1827 (FO 352/19B/7B), there seems to have been relatively little interaction between her and the government until it became apparent she had accumulated substantial debts.

‘HMG have no control over Lady Stanhope’

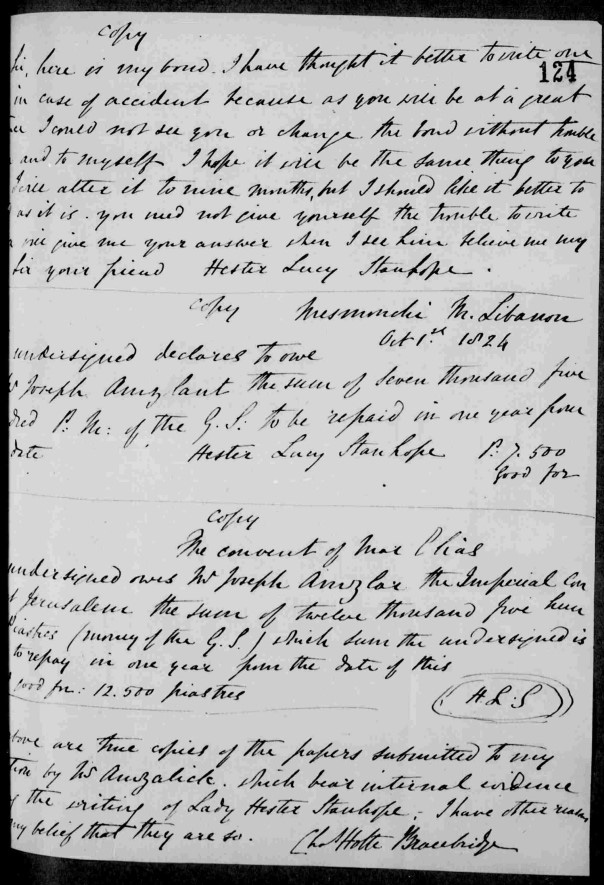

Under the Capitulations regime, the Ottoman Empire had ceded jurisdiction over British subjects to the British consular authorities. It had, however, retained jurisdiction where an Ottoman subject was involved. By 1834, Lady Hester’s debts were such that the Egyptian authorities got in touch with the British representative in Cairo, Colonel Campbell, ‘to obtain justice for the creditors’. Conscious of her rank, Campbell escalated the matter. The government, he was told, had ‘no control over Lady Hester Stanhope’ and could therefore not interfere.

By 1837, as requests from the Egyptian authorities kept coming, the Foreign Office was a bit embarrassed. The Egyptian minister had noted that when claims came from British subjects ‘against Turks or other natives of this country, the most ready attention was paid to them and justice was immediately rendered’. It was clear that if the debt wasn’t paid, Lady Hester might have to appear before an Ottoman court.

Her brother, Lord Stanhope, was made aware of the situation and, according to a memorandum on her case dated 1 May 1838, suggested she might pay her debt if she was told the British consul wouldn’t sign the certificate she needed to receive her pension until she had done so.

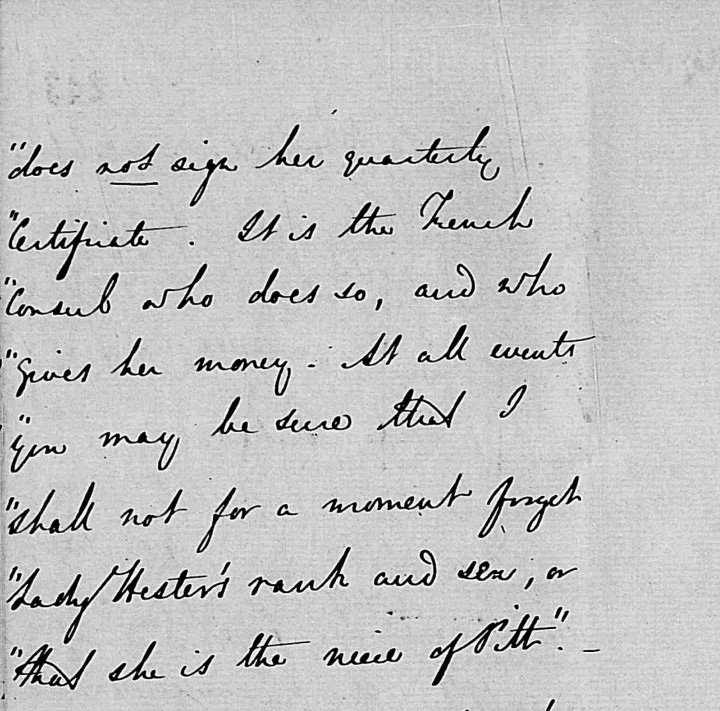

Campbell, who had to inform Lady Hester of this decision, felt he had been put in an awkward position. Acutely aware of who she was, he wrote:

‘At all events you may be sure that I shall not for a moment forget Lady Hester’s rank and sex, or that she is the niece of Pitt.’

FO 78/348

‘I shall go on fighting my battles, campaign after campaign’

Informed of the plan by Colonel Campbell via Moore, the British Consul in Beirut, Lady Hester started a correspondence war, firing acerbic, sometimes rather rude, letters. ‘I shall give no sort of answer to your letter’, she wrote to Campbell on 4 February 1838 (FO 78/342).

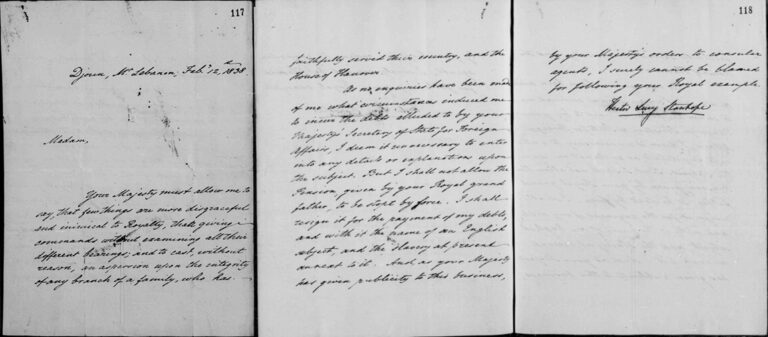

About a week later, she wrote to Queen Victoria, protesting vigorously. Her family, she said, had been loyal to Britain, and she expected to be treated with more consideration. No one had even bothered asking her why she had accumulated so many debts:

‘Few things are more disgraceful and inimical to Royalty than giving commands without examining all their different bearings (…). I shall not allow the Pension, given by your Royal grandfather, to be stopt by force. I shall resign it for the payment of my debts, and with it the name of an English subject, and the slavery at present annext to it.’

FO 78/334

On the same day, she wrote to the Duke of Wellington: ‘your Queen had no business to meddle in my affairs’. Her debts, she explained, had come from her desire to help poor people. In 1834, during what is now known as the Syrian Peasant Revolt, it had been reported that she ‘had given no less than 77 protections to different persons’.

The Foreign Secretary, Lord Palmerston, seemingly losing patience but still exercising restraint, wrote to Lady Hester himself to assure her that everything they had done was to save her the embarrassment of being dragged before an Ottoman court. From Lady Hester’s reply, it is easy to see that he had the opposite effect to that he had hoped to achieve.

‘If your diplomatic despatches are as obscure as the one which now lies before me, it is no wonder that England should cease to have that proud preponderance in her foreign relations which she once could boast of (…) I shall go on fighting my battles, campaign after campaign.’

She then took to the press. On 27 November 1838, The Times published the whole set of correspondence.

This prompted Dr Joseph Wolff, a missionary, to write to Lord Palmerston to correct some of the statements which had appeared in the press. He didn’t know Lady Hester personally, but had spent a fair amount of time in the same region and, he added, ‘she flogged 15 years ago my poor Arab servant’. He felt ‘the truth ought to be known’.

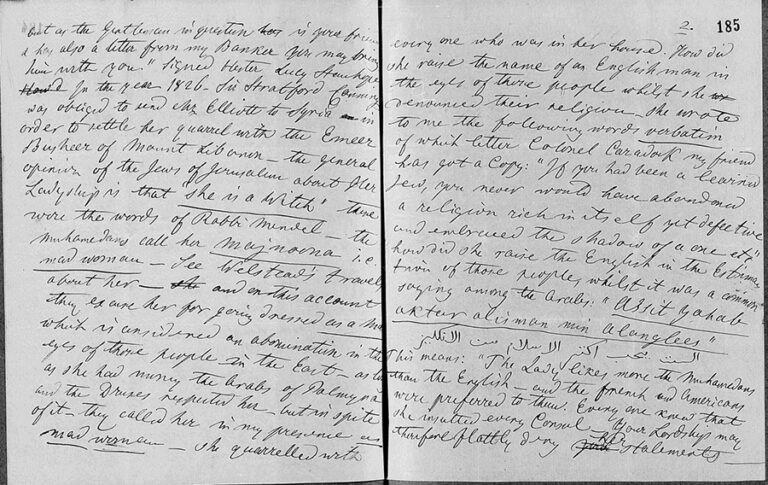

Interestingly, we get more information about Lady Hester’s colourful life from her detractor’s letter than from any other document we hold. He had many things to say about her debts, the way she was perceived in the region, and her general demeanour:

‘These debts were incurred many of them for foolish reasons – so for instance she gave Rabbi Levy from Hebron 7000 piastres for having remained up with her a whole night and conversed about the Messiah etc. (…)

The general opinion of the Jews of Jerusalem about Her Ladyship is that she is a “witch2 (…). The Mohamedans call her majnoona i.e mad woman, and on this account excuse her for going dressed as a man (…)

It was a common Saying among the Arabs: “Assit yahab aktar alislam min alanglees”. This means “the lady likes more the Mohamedans than the English” (…)

Everyone knew she insulted every Consul.’

‘It is right that Lady Hester should remain in Lebanon’

Lady Hester Stanhope died in Joun on 23 June 1839. In a letter to Lord Palmerston, she had threatened to entomb herself in her house if her name wasn’t cleared publicly. There is no evidence she did anything that dramatic, but by all accounts she didn’t go out much, if at all, in the few months preceding her death. As she had expressed the wish to be buried in her garden, Consul Moore travelled to Joun with an American missionary who performed a short service. According to her servants (28 in total), she had retained ‘till within a few minutes of her dissolution all her faculties’ (FO 78/370).

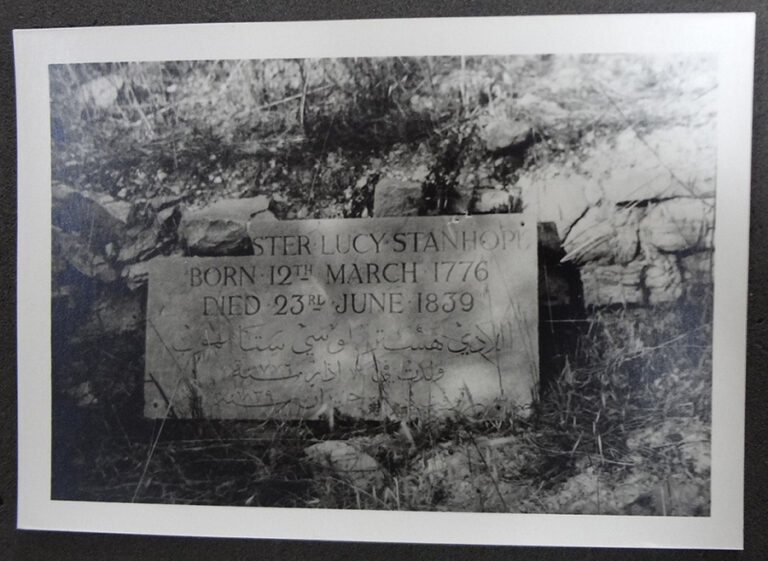

The devastating earthquake of 1956 took its toll and, by 1961, the tomb was badly damaged. The inscribed slab was broken, which, the embassy noted, ‘probably accounted for the café in Djoun from which one begins the walk to the grave being called “The Star Stain Hope Café”’ (FO 1018/117).

Lord Stanhope covered the cost of the repairs and, for £32, the tomb and its inscribed slab were restored.

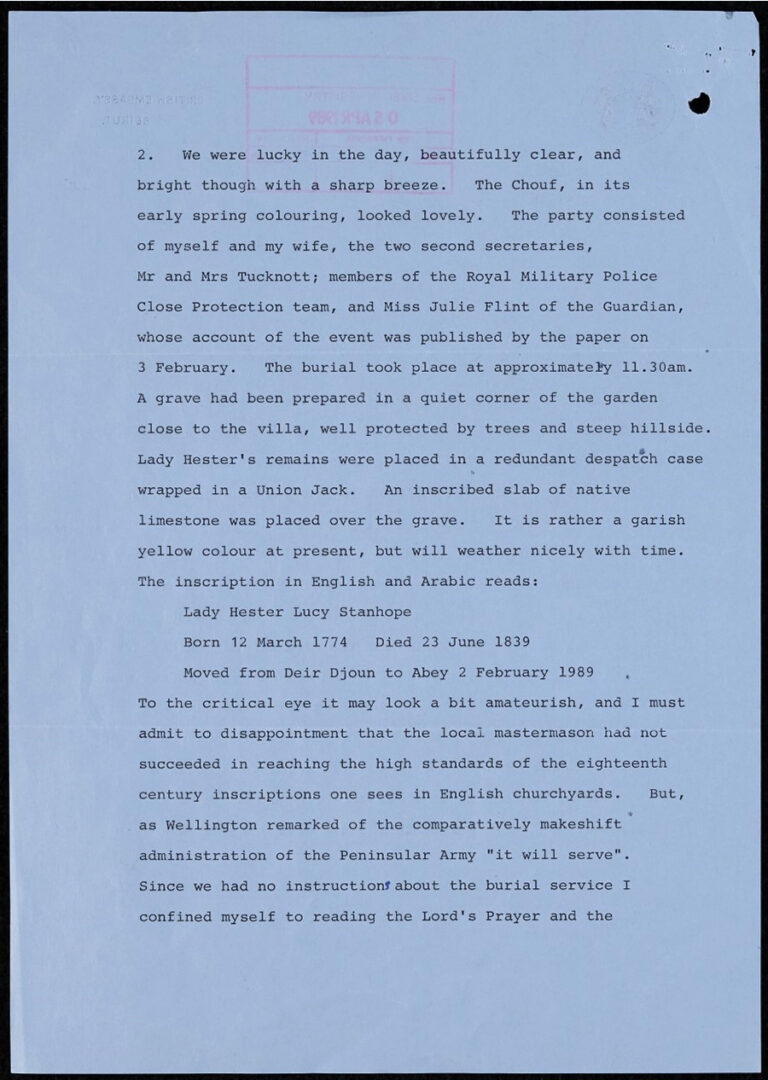

In 1988, it became apparent that the tomb had been vandalised. Alerted by the Red Cross, Allan Ramsay, the British Ambassador, came into possession of Lady Hester’s remains which, he later reported, were ‘stored in a grey cardboard box in [his] study’. The political situation in Lebanon was very unstable at the time but, ‘just in time before the latest round of bitter fighting’, Ramsay managed to organise the reburial of Lady Hester in the garden of his summer residence in Abey, just a few miles from Joun.

On 2 February 1989, ‘a beautifully clear day, and bright though with a sharp breeze’, Lady Hester was laid to rest ‘in a quiet corner of the garden, under a group of Mediterranean oaks’. Prayers were read, and the small funeral party laid flowers on the grave.

The residence at Abey was sold in 2001. In 2004 Lady Hester was moved again, her ashes scattered over the ruins of her house in Djoun. As Allan Ramsay noted in 1989, ‘it is right that Lady Hester should remain in Lebanon’.

Trailblazers: Women travel writers and the exchange of knowledge is open from 12 September 2022 and runs until 26 February 2023.

Documents on loan to Chawton House:

- FO 352/19B/7B, Folio 631: Letter from Stratford Canning to Lady Hester Stanhope recommending leaving Turkey

- FCO 93/5694, Item 10, folios 1 and 2: Account from Allan Ramsay to Sir Geoffrey Howe of the reburial of Lady Hester Stanhope, March 1989

Amazing character , laceless and most unconventional woman, I have been to Dhar el Sytt several times, a kind of pilgrimage where his ashes rest and where his soul still hovers…..