Over the course of the six months from January to July 2022, The National Archives’ Collections Care Department (CCD) hosted two placements as part of the KickStart scheme, a UK government initiative. The initiative aimed to increase and support the employment of young adults, aged 16 to 24, who were on Universal Credit and at risk of long-term unemployment.

Below are two blog posts written by KickStarters Sean and Naimah, describing their experiences, impressions and possible plans for the future, based on their time with the CCD.

Sean Slammon-Minas

As I have an interest in history, the KickStart placement stood out as a unique opportunity for me to gain valuable work experience and broaden my skill-set for future employment.

This opportunity at The National Archives has served as a great introduction to the cultural heritage sector for me, something that I might look to continue working in after KickStart. Having only worked a weekend job before, this has been my first foray into a typical weekly job, especially one as part of a huge (in terms of size and importance) organisation like The National Archives.

The main focus of my six-month placement was the Limp Parchment Binding Survey. During my first few weeks here, I was introduced to a plethora of terminology which was unfamiliar to me previously.

To explain what the project is, I need to first explain the core terminology. Essentially, the ‘Limp’ means soft/non-hardback cover. ‘Parchment’ is a material made from animal skin, usually calf, sheep or goat, via a series of processes resulting in a thin, yet sturdy material. It is the material used for all the covers, and in the 13th- up to the 16th-century bindings, it is normally the material used for the pages themselves. The term ‘Binding’ represents the book structure and its components. The ‘Survey’ is the collection of data from each individual binding we examine.

During the first couple of weeks, I was shown how both paper and parchment are made and the different techniques used in different parts of the world. Parchment was essentially phased out by paper, due to paper being more convenient and easier to mass produce. Parchment is still made to this day, albeit on a very small scale. This transition began in the late 15th century.

The Limp Parchment Binding Survey is a massive project where over a thousand bindings from the 13th to the 17th centuries are being surveyed. It is split into two phases. The first phase was to identify the numerous book construction techniques, the materials that were used to construct these bindings, and to describe any other characteristics that are unique and of particular interest. This data was then input into a specially designed survey form, where it was then analysed by one of the conservators on the team. This analysis paints a bigger picture on how prevalent certain features or binding techniques are across a large span of time.

The second phase of the project was the scientific analysis, to further analyse roughly 20% of the bindings. We took magnified photographs of the hair follicles on the parchment covers, using a hand-held magnification tool known as a Dino-Lite, with a mid- to low-range magnification lens.

The parchment covers were then sampled non-destructively using small erasers by gently rubbing the inside of the cover and collecting the shavings. These samples were sent off to a lab to identify which animal the parchment had come from.

The samples of the parchment covers and hair follicle photographs are sent to Beasts2Craft. Here’s the description of what they do, from their website:

‘Beasts to Craft: (B2C) will exploit bio-molecular and imaging methods, allied to craft knowledge, to document the first two stages in the story of the manuscript: (i) the livestock; (ii) the craft that turned skins into a writing medium. With the object in hand, Jiří Vnouček’s craftsman’s eye, supported by new imaging tools, can recognise the skill of the skinner and parchmenier, and can virtually reassemble the hide to estimate the size (age) of the animal. The distribution of hair follicles suggests fleece type and breed, whilst medullation of the fibres or the wounds from parasites can both give clues to the season of slaughter. The biomolecules (DNA and proteins) in skins inform on species, type/breed, and sex of the animals used.’

Beasts to Craft

In the first few weeks of my KickStart placement, I had daily presentations to prepare me for the survey, as understanding the vast amount of terminology and ways to easily identify specific elements in bindings was crucial to the success of the Limp Parchment Binding Survey.

The actual practical experience of doing the survey gave me a better understanding of the terminology and differences between certain methods of construction/attachments. Differentiating primary tackets from secondary tackets, for example, was a challenge in the survey, as it had taken some time to outline, define and gain a clear understanding of how to identify primary from secondary tacketing: tacketing being an alternative form of book binding to sewing.

Primary tackets attach the cover to the bookblock, but they also keep the sections of the bookblock together. If you were to remove the tackets, the bookblock would fall apart. Whereas secondary tacketing is when the purpose of the tackets is to solely attach the case to the already constructed bookblock.

A tool that has been extremely useful in my time here at The National Archives is Ligatus. Ligatus is an online reference tool for museums and researchers, used to define pre-industrial book binding terminology, essentially a dictionary for archivists

At The National Archives, items are sorted into many departments depending on what the content of the item is. The main department I have surveyed is Exchequer (E), which contains documents relating to financial accounts, sales and property. These can range from medieval army wages to sales of wood in the 16th century, to customs at Bordeaux when England controlled parts of France during the Hundred Years’ War. The bindings I surveyed ranged from extremely thick and large, to thin and flimsy, from uninteresting, to fascinating in terms of design.

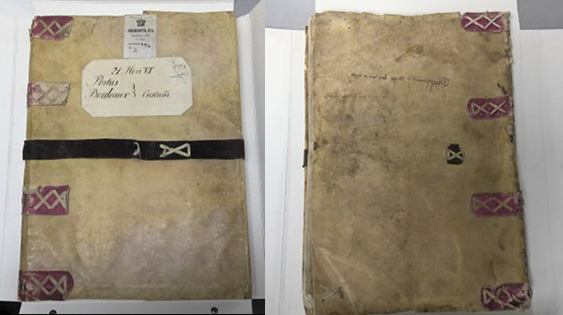

Below is a binding with interesting overbands. Overbands are reinforcements in the form of straps, usually of a thick, strong, tanned skin, secured to the spine together with a case-type cover by secondary tackets. The ends of the bands pass over the joints of the case and are attached to the sides with ornamental lacing.

Although the Limp Parchment Binding Survey was about the materiality of the bindings, I was just as interested in the written content of the bindings. Occasionally, especially with the later bindings, you can read certain sections of text and get a good understanding of what it is about. In the bindings that I surveyed, I encountered many interesting things such as dragon drawings found at the start of each section of this binding.

Naimah Kamal

When I first visited The National Archives, I came for university research and was surprised how extensive the archive was. I have some previous experience at the Palestine Exploration Fund, working with The Olga Tufnell collection. I worked on re-cataloguing the collection, which were the photographs taken by British archaeologist, Olga Tufnell, of her work and experience in Palestine in the 1920s and 1930s, and in Yemen in the 1950s and 1960s.

Apart from that, I didn’t have much knowledge of document handling or archival conservation. I was aware of conservation as a broader term but mainly with respect to the conservation and restoration of heritage sites.

Being part of the KickStart scheme has enabled me to work closely with some amazing medieval records. The project I worked on focused on collecting information on limp parchment bindings. The limp covers I surveyed are all made from parchment – a material made from animal skin which is treated with chemicals and then dried on a stretcher. Traditionally, when making parchment the animal hair was removed but I came across a few books covered in ‘hair vellum’, where the hair was left on! I’ve included a picture of one of these books below.

My day-to-day role had me working on surveying the bindings. This involved recording the different components that make up the structure of the book, for example how many visible holes there were for the book to be sewn (also known as sewing stations), or perhaps the type of sewing style used to bind the book together (there are many styles!).

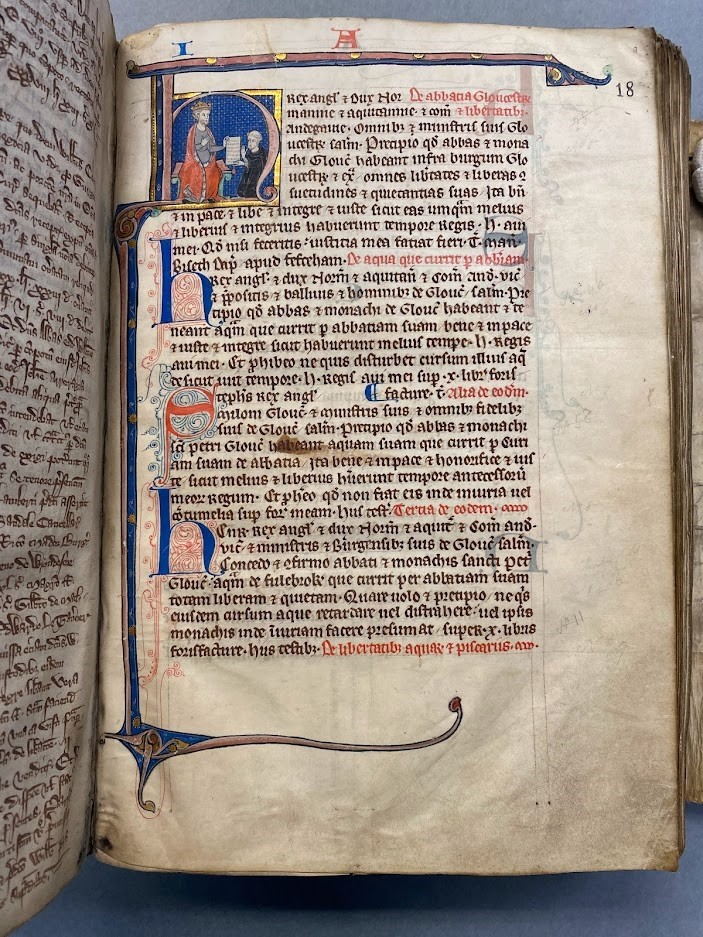

It is interesting to see how some of these bindings can have a cover which may look weak and dirty but can be surprisingly strong and clean. There can also be some fascinating content inside, for example illuminated pictures, like the one in the picture below which I found particularly interesting to look at.

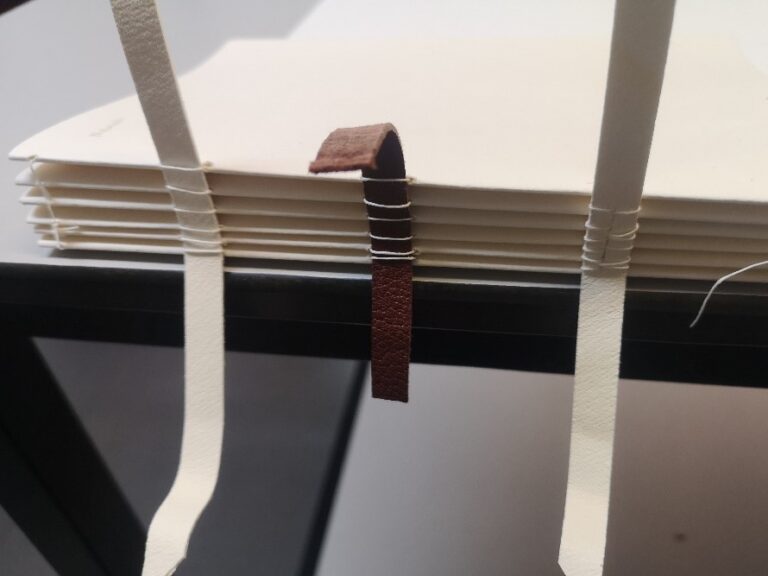

I’ve also learnt techniques of how to bind a book to be able to recognise the sewing techniques used to bind the bindings in the survey. Doing this really helped me identify the different sewing types, which were often so complex (just like any regular stitching on clothes). The binding model I made (see below) was sewn on three sewing supports: these are thin pieces of material that run horizontally along the spine of the text block (all the pages inside the book). In this model I used two different materials for the sewing supports: alum-tawed skin (the white one) and tanned leather skin (the brown one).

Another part of the project, categorised under ‘heritage science’, involved collecting samples and magnified images of hair follicles of the books for a biocodicology study. Biocodicology is the study of manuscripts and their DNA.

For the images, photographs were taken with a device known as a Dino-Lite – a kind of digital microscope. We were looking here for any trace of hair follicles which might show the direction the hair was shaved off or the type of animal this parchment belonged to (different hair follicles can determine this).

Non-destructive sampling involved taking some rubbings of the inside area of a parchment cover or the parchment text block. Once these eraser crumbs were used, they went into a small sample tube, which was then extracted from to test and help to determine the sex and species of the animal used to make the parchment.

Overall, I had a great experience. I have learnt lots of skills and information which I hope I can take with me with me into future opportunities. This placement at The National Archives has definitely widened my knowledge about archival conservation as a practice and the importance of it in the heritage world. I hope this blog reaches and inspires anyone who may not know a great deal about conservation as a practice.