This month is Stoptober – an annual media campaign started by Public Health England in 2012 to encourage people to tackle their addiction to nicotine. Sixty years ago smoking was a perfectly acceptable social habit which could be carried out in workplaces, pubs, clubs and on public transport. This blog looks at how the government began its long-running campaign to convince us all to take the dangers of smoking seriously.

Smoking and Health report 1962

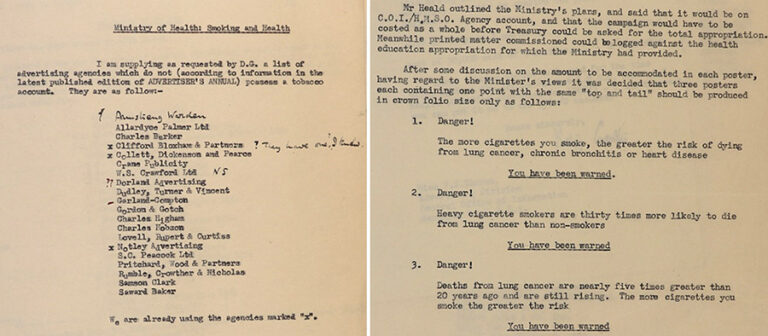

On 7 March 1962 the Royal College of Physicians published ‘Smoking and Health’[ref]‘Smoking and Health’ can be downloaded from the Royal College of Physicians website[/ref], a document linking tobacco to cancer and demanding government action. A BBC reporter at the time explained that ‘For some weeks now, tobacco shares on the Stock Exchange have been falling in anticipation of this report’[ref]BBC report on 7 March 1962, accessed 17 October 2021[/ref] and documents at The National Archives show officials in the Central Office of Information (COI) began discussing advertising campaigns even before the report was published[ref]Advertising Division: Ministry of Health: Smoking and lung cancer; finance and policy. Catalogue ref: INF 12/938[/ref].

The COI drew up a list of advertising agencies that didn’t hold accounts from tobacco companies, who could potentially advise the government on an anti-smoking campaign without a conflict of interest.

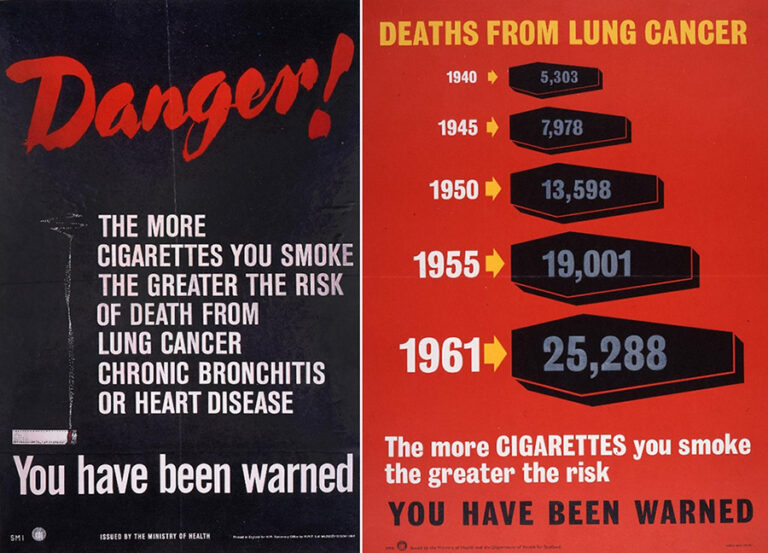

At the same time, under the instruction of the Ministry of Health, the COI was hurriedly preparing an initial series of three posters illustrating the dangers of smoking. The posters featured the stark message – ‘You have been warned’ – which the Director General of the COI, Sir Thomas Fife Clark, was not in favour of but went along with out of necessity, saying:

‘I do not want to conceal from the Ministry that I do not like “You have been warned” which seems likely to be counter-productive and in any case non-factual: but since we are told that it is a ministerial instruction and unalterable, we must of course submit.’

The line ‘You have been warned’ was repeated on later posters featuring coffins and graphs illustrating the rising amount of tobacco smoked and the associated increase in deaths from lung cancer. You can see more COI anti-smoking posters from the 1960s in our Image Library.

Anti-smoking films – ‘Smoking and You’ (1963)

Along with posters and leaflets, the COI used film to inform the public about the dangers of smoking. In June 1962 the COI commissioned Derrick Knight, an innovative documentary-maker, to provide an initial film treatment at a cost of £75, followed by a shooting script in August for the same price. In October, the production of the film, initially called ‘Smoking and Lung Cancer’, was commissioned for just over £3,000.

Documents show that it was aimed at the ‘general public, especially children and young people beginning to be interested in smoking – and parents’. The intended effect of the film was ‘to discourage smoking – and particularly to persuade children and young people not to take it up – by giving a factual picture of the risks involved’.

The film was later re-named ‘Smoking and You’ and given the following description:

‘A film showing the risks of cigarette smoking. The irritant and destructive effect of cigarette smoking on the throat and lungs is shown by diagrams and is dramatically illustrated by the breathless and distressed state of two people who have both been heavy smokers. Unglamorous aspects of smoking and its risk to health are contrasted with physical fitness and the pleasure this adds to living.’

You can watch ‘Smoking and You’ on the BFI player free of charge.

Anti-smoking films – ‘The Smoking Machine’ (1964)

A short time after the release of ‘Smoking and You’, the COI began work on a second film, this time aimed at children aged 9 to 12. ‘The Smoking Machine’ was directed by Sarah Erulkar, a prolific British-Indian short-film and documentary-maker[ref] Sarah Erulkar biography: BFI Screen Online, accessed 17 October 2021[/ref].

Documents in the production file for ‘The Smoking Machine’[ref]Production file for ‘The Smoking Machine’. Catalogue ref: INF 6/2092[/ref] show Erulkar did some research, talking to teachers and people actively concerned with the anti-smoking campaign in schools. This led her to conclude that ‘The facts that should be presented in this film, and the “moral tone” that should be taken, are quite clear, and seem to be accepted by all those to whom I have talked.’

Erulkar took the view that children didn’t need to be told exactly what lung cancer was. They would already understand the seriousness of the word ‘cancer’ and the film should avoid over-playing this point, particularly as it could make children worry about parents that smoked. Similarly, children didn’t need statistics except for a few easy to understand figures such as the fact that five times more people were killed by lung cancer than on the roads, and that since the facts about smoking became known, 60% of doctors had given up, with more doing so every year.

The important points the film needed to make were that smoking was not grown-up, clever, glamorous or ‘manly’, and that it wasted money and was difficult to give up once you had started. Erulkar’s research also showed her that the film had to avoid preaching or threatening:

‘The common feeling among all those I consulted is that to take too moral an attitude or to threaten with death, would almost inevitably have the opposite effect from the one we’re aiming at. Smoking will seem daring and “death-defying”, and many children will strongly resist the message. Further, we must never say “Do this” or “do not do this”, but must try to persuade the audiences on the level of “don’t you think it would be better etc”.’

Based on her research, Erulkar produced initial treatments using three approaches:

- Following groups of children in a school as they carry out investigations to find out the effect of smoking on health, and why people smoke.

- Using athletes and sports starts like Stanley Matthews and Roger Bannister to show the importance of keeping healthy, and using Bannister’s position as a doctor to back the argument up even further.

- A dramatic piece with children being detectives and solving the mystery of why people smoke.

The third option was Erulkar’s own favourite:

‘The children in the audience could follow the clues one by one, absorbing the message without resenting it, until they are led to the same conclusion as the children on the screen. The humour must be well thought-out, and the final pay-off strong and clear, even tough. But above all, this film has the great merit that it is worked out in an idiom that the children are used to – the TV adventure.’

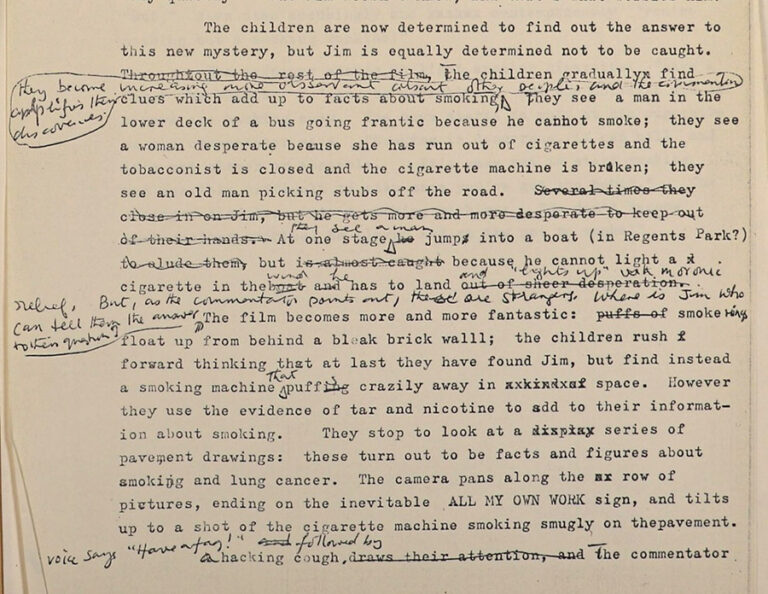

This approach was agreed, and in November 1963 the contract to produce the film was given to the Realist Film Unit for a fee of just under £7,000. The synopsis of the film reads: ‘Five children, their curiosity provoked by their friend Jim, a teenage cigarette chain-smoker, set out to discover why people smoke. They observe various addicts, and find an extraordinary contraption which smokes cigarettes automatically. The children chase and finally corner Jim, who, in revealing his secret, provides the young detectives with the vital clue.’

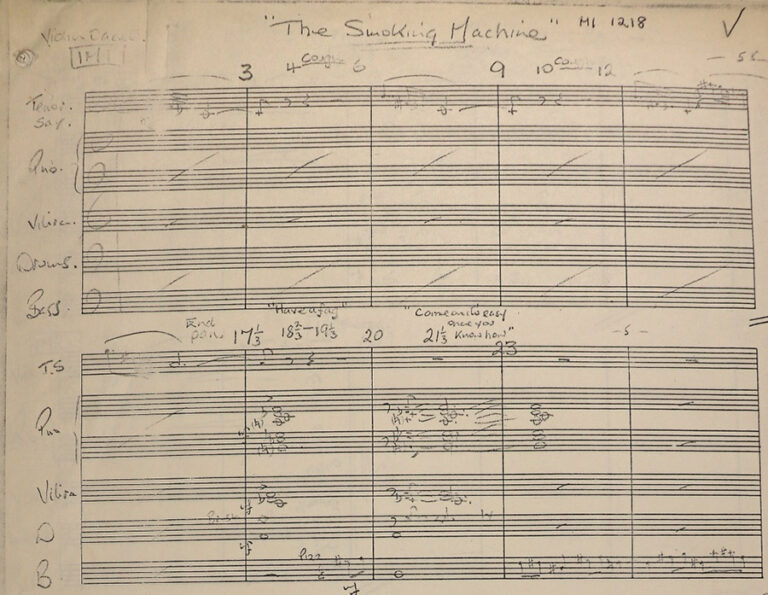

The original music score for ‘The Smoking Machine’, written by Edwin Astley, is also held at The National Archives[ref]Original music score to ‘The Smoking Machine’. Catalogue ref: INF 15/44[/ref]. Astley wrote, among other things, the theme tunes to TV shows ‘The Saint’, ‘Danger Man’, and ‘Randall & Hopkirk (Deceased)’. His daughter married Pete Townsend of The Who.

You can watch ‘The Smoking Machine’ on the BFI player free of charge.

The BFI’s own blog, The first anti-smoking films: how a nation started to quit by Ros Cranston and Patrick Russell, offers a fascinating exploration of the styles and techniques employed by Derrick Knight and Sarah Erulkar in these early anti-smoking films.

Conclusion

The government’s reaction to the Royal College of Physicians’ report in March 1962 was certainly fast, even if in the early days the Ministry of Health and COI didn’t agree on the tone of the message used on posters. Within months, skilled film-makers had been commissioned to put the message across to children and young people in a way that they would understand and respond positively to. The COI continued to make anti-smoking films, addressing new concerns such as passive smoking. A particularly memorable campaign, ‘Smoking Kids’, from 2003 pulled no punches, showing babies and young children looking as though they were breathing out smoke[ref]‘Passive Smoking: Smoking Kids’ is available on BFI player[/ref].

More COI films

This year (2021) marks the 75th anniversary of the COI which used films, posters and leaflets to educate, inform and influence the public between 1946 and 2011. The National Archives has been working with the British Film Institute (BFI) and the Imperial War Museums (IWM) to highlight some of the many thousands of films made by the COI.

You can watch more COI films on the BFI player, the IWM films website and on The National Archives website. You can read more about the COI on my earlier blog, Connecting collections amid COVID-19, written together with the BFI and the IWM, and by following the hashtag #COI75 on Twitter.

The tone and messaging on ‘the smoking machine’ COI film was spot on, even by today’s high standards in public information broadcasting.

It would have been easy to be alarmist, which would possibly have had a negative effect. Glad to see smoking levels in our population continue to come down. My worry is that there are still many unknowns in vaping – could this be the next big social health issue?