Using the Tudor Chamber Books resource

An exciting aspect of working at The National Archives on partnership projects like Tudor Chamber Books 1485-1521 is that the main sources are close to hand. That makes it easier to explore document trails when a nugget of information catches the eye.

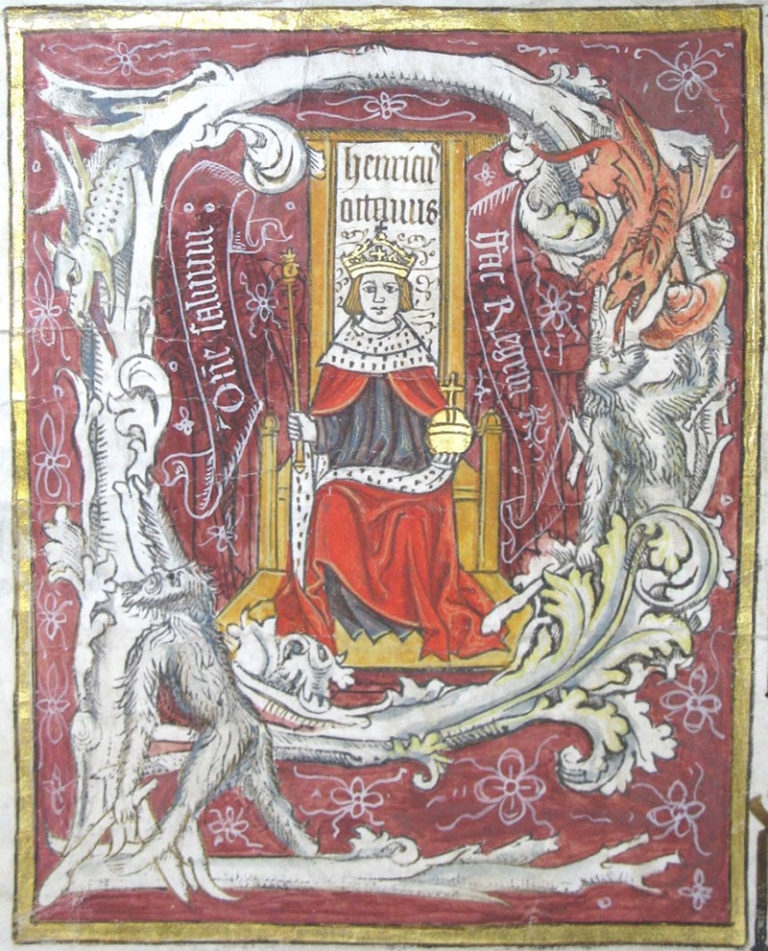

The project website allows searching and browsing of digital transcripts of the main records that show how Henry VII and young Henry VIII raised and spent money through their chamber: the part of the Royal Household managing the cash most closely connected to the king’s personal power. Their chamber records survive, unlike those of many earlier rulers – evidence that gets us closer to daily life at court and to the concerns of the country’s leaders. Yet the summary figures in the books disguise complex processes and records. The following case study highlights a starting point found in the chamber evidence that links to more unfamiliar and informative early Tudor documents.

The Queen rules the realm

A key period in shaping Henry VIII’s rule came in 1513. By mid-May, the king was ready to lead an army across the Channel to attack the French. The campaign was part of England’s promised role in the Holy League from October 1511, to aid the defence of the Pope’s lands in Italy from France and her allies. The English used Calais, their last outpost in France, as the assembly point for an army of at least 25,000 soldiers, which set off at the end of June to attack the town of Thérouanne. The aim, initially, was to draw French troops from their deployment in Italy.

Queen Katherine became governor of the realm and Captain General of England at her husband’s departure[ref]Letters sent by the king required that during his absence and from 30 June 1513, Katherine would be General Governor and Rectrice of the realm. The style of official documents would change to show that they were issued in her name – Teste Katerina Angliae Regina ac Generali Rectrice Eiusdemi (witnessed by Katherine, Queen of England and governor of the same), C 54/381, m. 2d.[/ref] She was aged about 28 and was, by then, vastly experienced in her own right as a diplomat, princess and queen. Her upbringing in Spain at the side of her mother, Queen Isabella of Castile, had coloured her childhood with high politics and war.

By the summer of 1513, Katherine ruled England through a privy council. She could make grants and appointments, taking all steps to defend the realm. If her councillors believed that Katherine would defer to their experience during Henry’s absence, events soon changed that view.

Crisis and war

Part of France’s strategy to resist the League was to activate the ‘auld alliance’ with Scotland and distract the English by building the threat on the border with Northumberland. Most English nobles were already in France with the king, but border lords like Dacre and Clifford remained behind. They were fully aware of Scottish preparations. James IV of Scotland was committed to take advantage of King Henry’s focus on France. Despite risking papal censure for breaking the treaty of ‘perpetual peace’ agreed with Henry VII in 1502[ref]E 39/92/12.[/ref], the Scots soon tested English readiness.

Organisation of the defence rested with Thomas Howard, earl of Surrey. Aged about 70, Surrey was one of the oldest of Henry VIII’s counsellors. Yet his experience in governing the north in the 1490s made him indispensable, as the region looked vulnerable to the main Scottish attack when more than 30,000 men crossed the River Tweed on 24 August. Surrey’s efforts had prevented full-scale war in 1497, but he knew he had to fight this time. By 1 September, at least 25,000 English soldiers were on the border under his command[ref]The English numbers are calculated from E 101/56/27 and British Library, Egerton MS 2603, fol. 30r.[/ref].

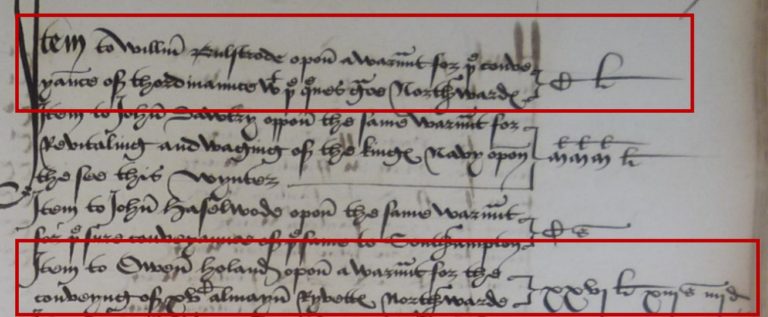

What Surrey probably had not expected was that Queen Katherine would become so actively involved in England’s response. Two entries in the chamber books from early September 1513 stand out:

Item, to William Bulstrode upon a warrant for the conveyance of the ordinance with the queen’s grace northwards – £100.

Item, to Owen Holand upon a warrant for the conveying of 1500 almain rivets northward – £36 14s 4d.[ref]E 36/215, p. 267.[/ref]

An army for the North

As the Scottish threat grew, in a letter dated 2 September to Thomas Wolsey in France, Katherine revealed that she was ready to head northwards[ref]SP 1/5, fol. 28r.[/ref]. These short notes show that Katherine personally led what was left of the king’s artillery towards the North. She took 1500 suits of armour, called Almain Rivets[ref]A light body armour for cavalry or foot soldiers that originated in Germany. The design was distinctive for its overlapping sliding riveted plates at the shoulders and thighs.[/ref], on her journey – all part of her direct responsibility for organising England’s deep defence. On 3 September, she asked Sir Thomas Lovell, another of her husband’s loyal advisers, to muster an army in the Midlands. Katherine used all her royal authority to command the lords, mayors, sheriffs and officials to assist her in safeguarding the realm, upon their loyalty and allegiance[ref]C 66/620, m. 3d.[/ref].

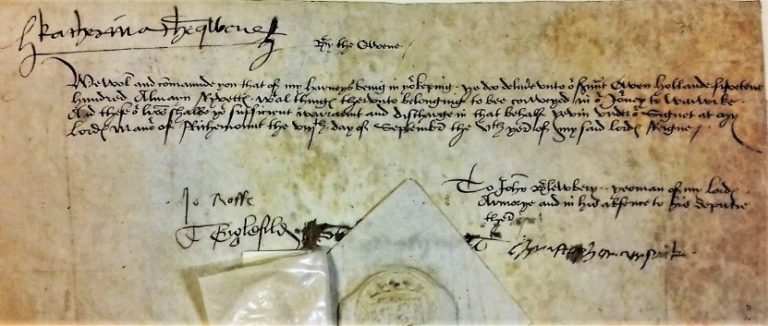

The first chamber book note is explicit about the queen’s role, the second less so. A document that links the two, however, is the warrant that Katherine signed at Richmond on 8 September, commanding the yeoman of the armoury to deliver the armour to Owen Holand. This survives among the working files of John Heron, the treasurer of the chamber.

We will and command you that of my harness being within your keeping, you do deliver unto our servant Owen Holand fifteen hundred Almain Rivets…to be conveyed in our journey to Warwick[ref]E 101/517/23, no. 36; Owen Holand was a squire attendant in the queen’s chamber, LC 2/1, after fol. 198.[/ref].

Holand’s bill of related costs is also part of Heron’s papers and shows how the 1500 pieces of armour were transported[ref]E 101/517/23, no. 38.[/ref]. Eighteen large pipes (or casks) arrived at the Tower armoury. It took three days before seven labourers and the armourers had finished assembling, ‘couching and trussing’ the armour into the barrels. The cooper of the armoury fitted hoops and lids before porters loaded the casks onto carts to begin the slow journey to the Midlands.

Leading from the front

In the invasion crises of the previous reign, Henry VII had gathered his power at Kenilworth castle. In 1513, nearby Warwick was the destination of the queen, her guns and likely muster point for Lovell’s troops. Instead of seeking refuge in the secure Tower of London and letting her husband’s councillors take the lead, Katherine’s decisive action moved her closer to danger and confirmed her role as national commander.

She would not have been involved in any battle that might have occurred had the Scots broken through on the border, but her determination to be nearby to organise the country’s stretched resources sent all the right signals to the people she temporarily ruled.

The last queen to lead an army in England was also foreign-born. Margaret of Anjou, wife of Henry VI during the civil war of 1459-61, had taken up some of the political and military roles that her weak husband was unable to deliver. Her opponents attacked Margaret’s assumed role as unnatural and presumptive. In 1513, Katherine of Aragon’s tenacity and leadership in a national crisis had the opposite effect. Her galvanising actions were a personal public relations success.

Managing the aftermath

The decisive battle of Flodden happened on 9 September. King James, scores of his nobles and thousands of their men perished. When news of the English victory reached southern counties a few days later, the first load of Tower armour had just arrived at Uxbridge. Katherine was then at Buckingham and on 16 September wrote to the king from Woburn Abbey, announcing Surrey’s triumph.

Katherine continued to oversee negotiations for a truce with the Scots, and showed great skill in her diplomatic messages to her man on the spot, the bishop of Durham. She led the drafting of letters to Queen Margaret of Scotland (Henry VIII’s sister), and in October sent a friar to Edinburgh to comfort her sister-in-law, but probably also to gather information[ref]British Library, Cotton MS Caligula B VI, fol. 40r.[/ref]. At the same time, Katherine instructed Lord Dacre to assert King Henry’s right to become guardian of his nephew, the young James V of Scotland – potentially re-opening the troubled English claim to overlordship of Scotland[ref]SP 1/5, fols 41, 70.[/ref].

Katherine’s visible and politically active role in running the country until 22 October showed her determined personality. She sent Henry a piece of James IV’s coat and wanted to deliver his body too, ‘but our Englishmen’s hearts would not suffer it’[ref]British Library, Cotton MS Vespasian F III, fol. 33r-33v.[/ref]. At that stage of her life, as Henry’s regime sent thousands of English soldiers to fight on the Scottish border, in France and at sea, Katherine was an ideal partner for her dynamic and aggressive husband. The chamber books and related papers can still offer much to deepen our understanding of how Henry and Katherine’s marriage developed, changed and soured over the following 25 years – a relationship that came to have a powerful influence on the course of the nation’s history.

I think you mean Margaret of Anjou was seen as presumptuous (overweening) not presumptive (presumed to be something, as in heir presumptive)

Always knew our Katharine was a true warrior Queen. Although she didn’t fight as she did in the series the Spanish Princess, encased in pregnancy armour, Katharine was very much at the centre of arrangements with the weapons and muster. She was more suited to rule than Henry.

My PhD dissertation has a lot more information about her activities during this time. For example her residence, Baynard’s Castle, was the centre of operations in London. The treaty to enter the League of Cambrai with her father’s ambassador had been signed there too. I also documented the arrival of canons from Spain and gunpowder from Italy.

Finally, I found the payment for the crown that she had made to lead the army. It was adorned with a sapphire.

Great to read. Thank you

I wish Queen Katherine had mustered an invasion to dethrone her unfaithful and despotic husband to ensure Mary’s enthronement and tge realm’s peace and stability.