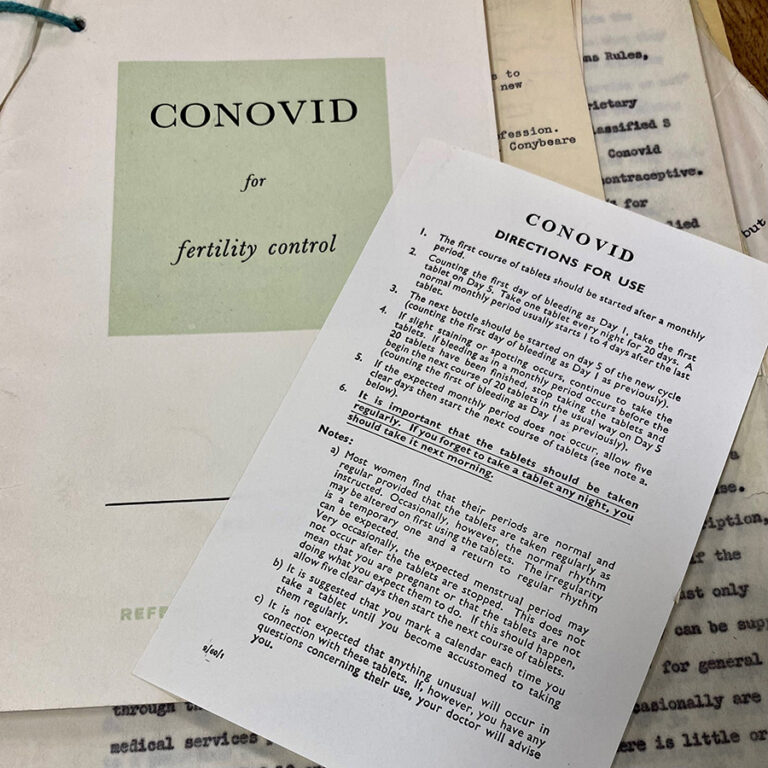

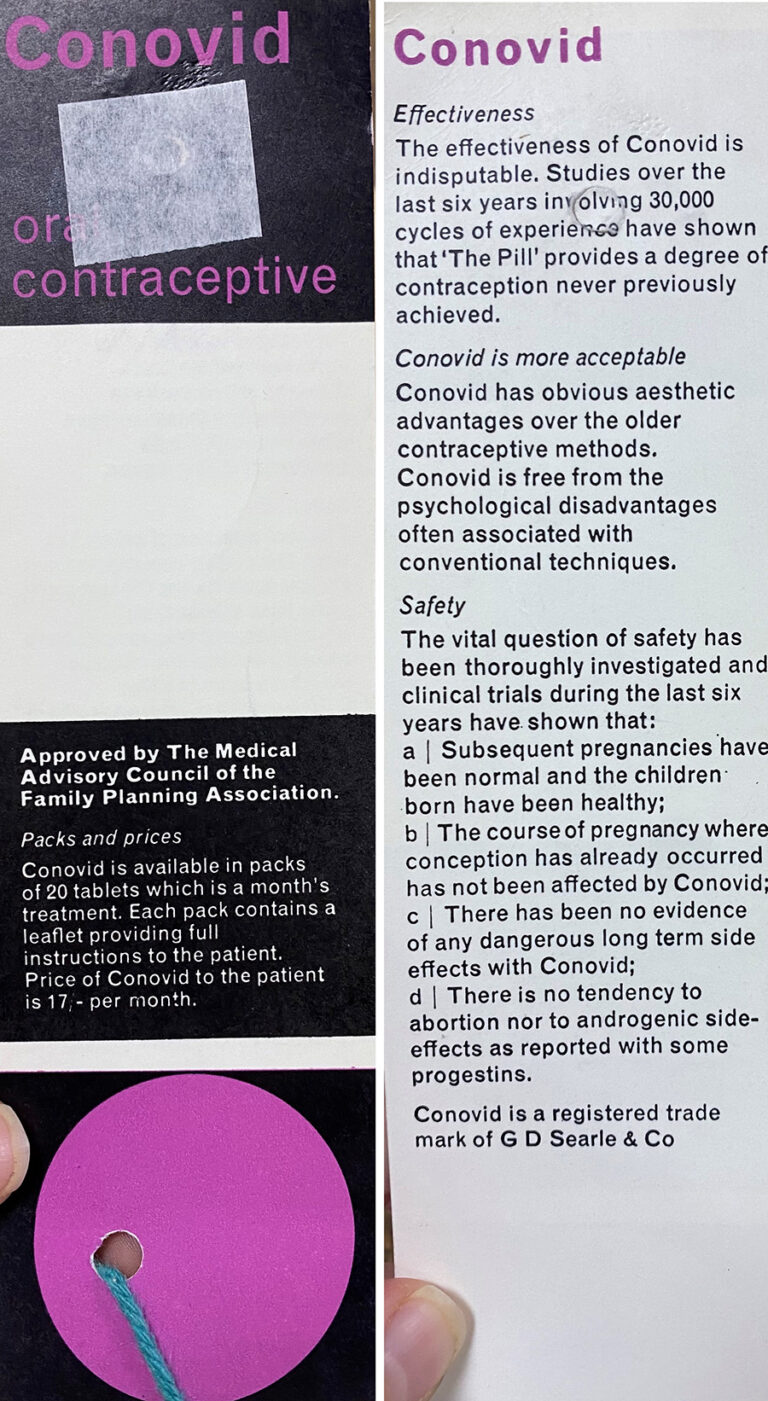

On 20 January 1961 Searle & Co wrote to the Chief Medical Officer of the Ministry of Health to ‘give advance notice of our plans for the introduction of an oral birth control tablet’.[ref]Oral contraceptives: policy. The National Archives, MH 135/108.[/ref] This hormone-based product had already been on the market in the UK for three years, but under a different name and for more palatable gynaecological use. It was to be sold under the name Conovid. Whereas earlier contraceptive pamphlets were sent in to the government as items of concern, Searle & Co were reaching out to the government themselves.

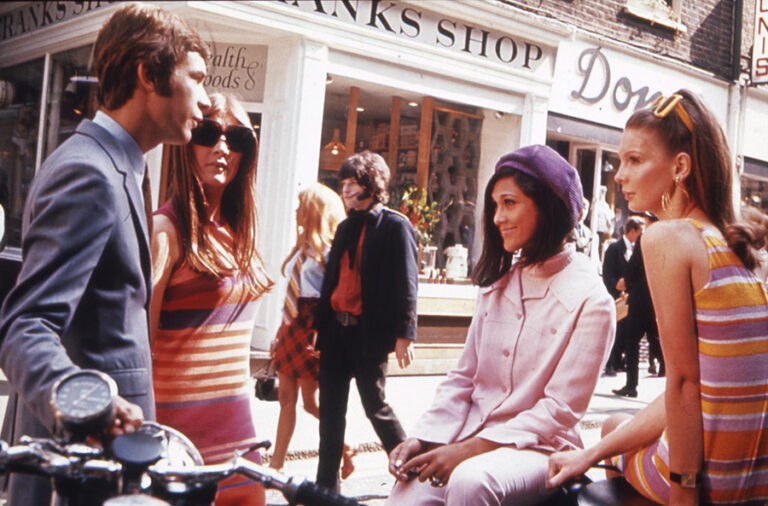

By February 1961 it was reported that full details of Conovid had been sent out to more than 20,000 manufacturers[ref]MH 135/108.[/ref]. At this time, the UK did not have a system for the pre-approval of such drugs. Whether the government liked it or not, change was coming. This development framed the start of the new decade that was to become known as the ‘Swinging Sixties’. Prolific fashion designer Mary Quant described life before and after the pill: ‘The perpetual anxiety. It was a real revolution.’[ref]Fifty years of the pill | Sexual health | The Guardian.[/ref]

The advent of modern birth control

The pill had originally been developed in America, where it was licensed as Enovid from 1960 (availability was determined at a state level). The same pill had been undergoing trials with several hundred married women volunteers in Birmingham and Slough. By October 1961, the British Family Planning Association had added the pill to its Approved List of Contraceptives – a significant move, as they were the primary provider of family planning services in the UK.

Government records reveal a significant amount of behind-the-scenes discussion and concern about getting their approach to this new contraceptive right. As you may expect, there is a notable lack of women’s voices in these files.

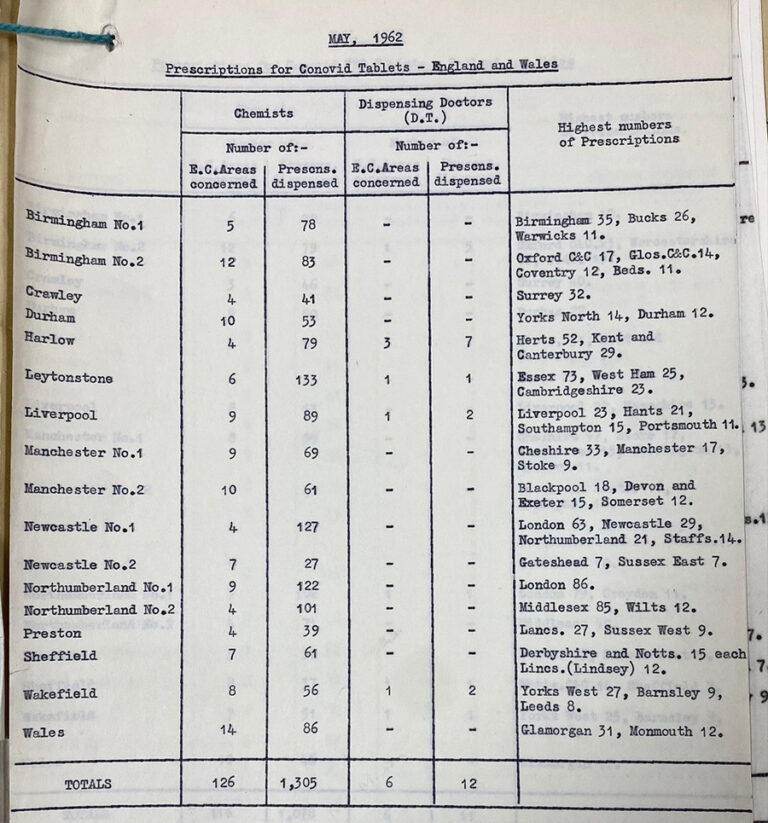

While the pill didn’t require a medical approval process for sale, it did raise many questions. Was this something that should be provided on the NHS? If so, to who and at what cost? Prior to this point the NHS essentially didn’t involve itself in the administration of contraceptives, but hormonal contraceptives required more medical advice to be given. The pill caused controversy for many reasons: firstly it was a preventative pill essentially offered to healthy people. Secondly, one of the biggest concerns was the potential cost. One government memorandum recorded that prescription charges would be about £11 per person per annum: ‘If this became really popular as a contraceptive the annual cost at this price could soon match the rest of the drug bill.’[ref]MH 135/108.[/ref] As this was a new product, demand was unclear, but it was anticipated to be significant.

Furthermore, it opened up moral debates and concerns about the role of sex in society and explicitly made sex about more than just procreation. Comments in a Ministry of Health file from May 1961 highlighted some of the more moral concerns: should these more reliable contraceptives be available to both married and unmarried women? Would the government essentially be encouraging a more permissive and potentially promiscuous society if unmarried women were offered the pill? A government official noted: ‘a woman has, I suppose, precisely the same rights under the NHS whether she is married or living in sin.’[ref]MH 135/108.[/ref]

Pressure was mounting for the government to take an official line. Throughout the summer of 1961, letters from the British Medical Association repeatedly requested government clarity.

Contraceptives on the NHS

After much behind the scenes discussion, on 4 December 1961 Enoch Powell, Minister for Health at this time, announced that the pill would indeed be available on the NHS. The pill was to be given to women whose health was put at risk by pregnancy and this was at the doctor’s discretion.

Labour MP Marcus Lipton asked Powell a pertinent question:

Mr Lipton: ‘Is it left to the doctor to decide whether these pills shall be prescribed both for married and single women?’

Mr Powell: ‘It is always for the individual doctor to decide in each case what are the medical requirements.'[ref]HC Deb 4 December 1961 vol 650 cc922-3922, Birth Control Pills (Hansard, 4 December 1961) (parliament.uk).[/ref]

As noted in the days after this announcement, ‘clear cut, medical reasons are very much in the minority.’[ref]Letter by R E Ford, 8 December 1961, MH 135/108.[/ref] In practice, only a limited number of married women generally received the pill in these early days; nevertheless this was the first step towards wider change. It indicated an important shift in the government’s approach to sex and contraceptives.

While earlier birth control methods were commonly used and visible in society, the pill:

- put women primarily in control of conception, and their bodies;

- was preventative, and didn’t need to be applied at the last moment;

- and most importantly, if used correctly, it was far more reliable than most other forms of contraceptives.

This all happened at the beginning of the 1960s, a decade that was to eventually see homosexual law reform, the mini-skirt and the Beatles. For women, it was the decade that would bring divorce and abortion reform. And the pill certainly played a part in this shift towards a more permissive society.

‘Sex on the State’ – further legislation

The initial House of Commons announcement was only the beginning. 1967 brought the NHS Family Planning Act, which enabled family health clinics to give contraceptive advice to unmarried women, giving many more women access to the pill. Despite this, there was significant stigma for unmarried women accessing it. Anecdotal stories talk of unmarried women passing around rings in doctors’ surgeries, in an attempt to appear married or engaged so as to be more likely to be prescribed the contraceptives that they were entitled to.

From 1 April 1974, a reorganisation of the NHS meant all contraceptive advice and supplies became accessible free-of-charge, regardless of marital status. Sir Keith Joseph, Secretary of State for Health and Social Services, announced the government’s decision that ‘family planning will become a normal part of our health arrangements’[ref]Family planning: provision of free services and contraceptives, 1973-1974. The National Archives, T 227/4153.[/ref]. Pockets of public backlash remained, with the Telegraph running with the headline ‘Sex on the State’, speculating that free birth control for all would cost the tax payer £1 million[ref]Sex on the State’, Telegraph, 1 April 1974. T 227/4153.[/ref]. There was also a legitimate worry about hospitals and clinics not being able to meet the demand of all the extra medical appointments that would be generated.

‘It was a real revolution’

The pill has since been widely accepted in society. While other contraceptive methods have been developed, it remains the most popular contraceptive in England, with approximately 3.1 million women taking it[ref]‘Revealed: pill still most popular prescribed contraceptive in England’ | UK news | The Guardian.[/ref].

It is hard to quantify the huge impact such a small pill has had on women’s lives, ultimately giving women greater certainty and choice. As a more effective birth control option, it has enabled women to choose when, or if, to have children, to increasingly move in to the workforce, to be more financially stable and to prioritise their careers. Significantly, it has also given people greater sexual freedom: to have sex for reasons other than child birth. The approval to give the contraceptive pill on the NHS 60 years ago also illustrated a significant shift in the role of the government and its involvement in issues concerning sex and family planning.

The pill continues to be debated and at times still attracts controversy. While the male contraceptive pill remains elusive, it is important to remember what the contraceptive pill initially gave women: greater control over their own bodies. At the time it was significant that this control was put in the hands of women.

At the time oral contraception became available to women I was a social sciences mature student. When a hoped for job failed to materialize I decided to research and write a book on the new contraceptive from a sociological point of view. Entitled ‘The Folks that live on the Pill’ – The Ideology of Oral Contraception’ I was soon commissioned by a UK publisher. Over the next few years, i explored various avenues of research about how the pharmaceutical companies were using a range of techniques to promote the Pill. These included adverts in medical journals, using photos of women – all young, white and attractive – and packaging of the pill under the slogan ‘Now the pill that suits her best in the pack that pleases her most! Sadly, i was unable to finish the book due to competing demands on my time as a social work academic. Two years ago I passed all my research notes, draft writings etc. to the Wellcome Institute in London. They are available there to anyone who might wish to read more on this hugely interesting topic!

Soon after the wider spread availability of the pill, I asked my GP to prescribe it for me. This provoked huge embarrassment: an unmarried undergraduate, with no marriage on the horizon, – too shocking to contemplate. I was told to return when I had the appropriate ring, and a date fixed for the big day (This was North Wales in the mid-1960s).

Eventually I did just that, and although my early prescriptions were not ideally suited to me, the Pill did the trick. It gave me control, and the freedom to establish my career before starting a family. I have always been grateful to those who developed this wonder-package.

As student nurses in the early 1980s we were told there was a 1 in 12 chance of breast cancer. Apparently now it is 1 in 7. Is there any link between the Pill and breast cancer?

I was a patient of the Family Planning Association in the days when you had to bring your husband along when you registered to “prove” you were married. I found the whole atmosphere rather patronising, as if a graduate of 22 was barely able to take important decisions by herself. The staff were all female, but it seemed as though the patriarchal society (though I wouldn’t have put it in those terms at the time) was using the FPA staff to put forward traditional male values. Men could have sexual freedom as they always had, but that of women must only be granted with great care. The real revolution was of course allowing unmarried women to take the pill – at the time I found this quite astonishing. We were still in the era of the Irish homes where they imprisoned the mothers and exported the babies to the USA.

The pill was my lifeline. We already had two children when I found my (now ex) had been making holes in my ‘Dutch caps’ – he was also very abusive, physically and emotionally. My doctor listened to my woes, then told me he had the answer – ‘the pill’ had just arrived. Without it I doubt I would still be here (am in my early nineties). The marriage ended a few years later and our two children stayed with me (thanks to a wonderful probation officer, efficient solicitor and perceptive judge).

I have always considered the Pill the best invention 0f the last decade. I applaud and appreciate all the medical scientists who put all that work in. I myself have 3 adult children who were very much wanted and welcomed. It is not the case that women don’t want a family, they just need some control of this part of their lives.

I was a nurse in the 60’s and we saw women admitted who had strokes, blood clots, and even died. It was said it was a result of the early type of pill. No one ever mentions that. There has been mentions of a link between the pill and breast cancer for many years. Catherine Heckman (previous letter) mentions that it is now 1in 7. I have often felt there was a link. There are too many very young women being diagnosed with this particular cancer. Because of what I witness as a young nurse I wouldn’t take the pill when I married.

So glad, Marian, you had the luck to meet enlightend professionals

The pill was indeed a wonderful advance for women even though early versions brought some complications. Interesting that it remains the most popular contraceptive despite the development of a number of long lasting alternatives. What you should add is that no contraceptive is infallible and that abortion is an essential backup , now itself brought on by two pills and, during this COVID 19 crisis, largely taken at home without medical supervision.

I find these first hand accounts of women being prescribed the Pill in the early days fascinating. My Mum took it too, so I learnt about it then and later took it myself. Having just achieved my BA in History at the grand old age of 62, I actually covered off the subject in my finals’ paper under the modernisation of medicine in the 20th century. Dream question!

1965: My son was 18months old and I was planning to leave my husband when I was confirmed pregnant on my 21st birthday, He was born in October that year.

1966: January – I went to the Family Planning Clinic and was told that I needed my husband’s written permission to use contraceptives. I was indignant but was told that he had the right to father as many babies as he wanted even though I was the person who would give birth etc. I was even more indignant but went away with the form for my husband to sign.

My mother had accompanied me to the Clinic and was just as indignant. She wiped my tears and said not to worry – we would just sign his name on the form ourselves.

So we did. I had no more babies and before Steven was 1yr I had left the marriage and I divorced him on the grounds of ‘physical & mental cruelty’

As a single mother I brought up my lovely sons, and trained as a teacher. Their father did nothing to support them and did not keep any further contact with them after Steven was 4yrs.

I thank my lucky stars that I was able to access safe and affordable contraception. Without that our lives would have been very different.

They were worried about the cost to the tax payer! Just an excuse. Contraception is highly cost effective. We always said £1 spent saved £12. I expect that still holds true. I’m ashamed how judgemental doctors were back in the day. In the 1980s a female GP told me I was irresponsible for NOT being on the pill! I hadn’t had a boyfriend for over a year…..

I had terrible irregular, painful periods and in 1974 my mother took me to the doctors to see if there was any support for me. I think she knew he would offer me the pill. I had been going out with my boyfriend for about 6 months and planned to get engaged. It was her way of ensuring I didn’t get pregnant. She had never talked to me about the facts of life or whether I was having sex. It was something mothers didn’t do. But it does show that there were ways round getting the pill.

My childrens father, Michael john kennedy harper discovered the compound for

Tamofican while researching birth control compounds at ICI in the early 1960,s.

Although I would agree that the contraceptive pill gave women a measure of freedom and control, it was interpreted in a different way by some men. Women were EXPECTED to be on the pill, so that men no longer had to take responsibility for using condoms, nor the responsibility for any condom failures. Women’s rights to say NO, were weakened.

As for accessing the oral contraceptive as an unmarried woman – I was able to do so with ease as an 18 year old at the Brooke Advisory clinic in Bristol in 1972. Maybe I was one of the lucky ones!