Maps have been in the news again recently with the opening of a new musical about the life and work of Phyllis Pearsall, the originator of the popular A-Z street plans. The tale of how the remarkable Mrs Pearsall walked 3000 miles to map the streets of 1930s London has achieved the status of legend. Indeed, much of it is thought to be just that: a legend, or at least an exaggeration of the truth. [ref] 1. See, for instance: Simon Garfield, On the Map (London, 2012), chapter 15. [/ref]

Today’s blog post tells another story about women and maps in 1930s London. Although less iconic, and perhaps less satisfying than the story of Mrs P, it is definitely authentic.

The scene of our story is the Land Registry, a government body that was – and still is – responsible for recording property ownership in England and Wales. [ref] 2. For more information about the early history of the Land Registry and its sometimes difficult relationship with Ordnance Survey and the Treasury, see: Geraldine Beech, Cartography and the state: the British Land Registry experience, Journal of the Society of Archivists, vol 9, no 4 (1988), 190-196. [/ref] The tale’s source is three files of correspondence and other papers about the employment of women as junior staff. [ref] 3. LAR 1/154, LAR 1/155, LAR 1/156. [/ref]

Wanted: women to draw maps. No experience necessary. Starting wage £2 a week. Apply to His Majesty’s Land Registry. Catalogue reference: LAR 1/154, job advertisement issued on 9 January 1935.

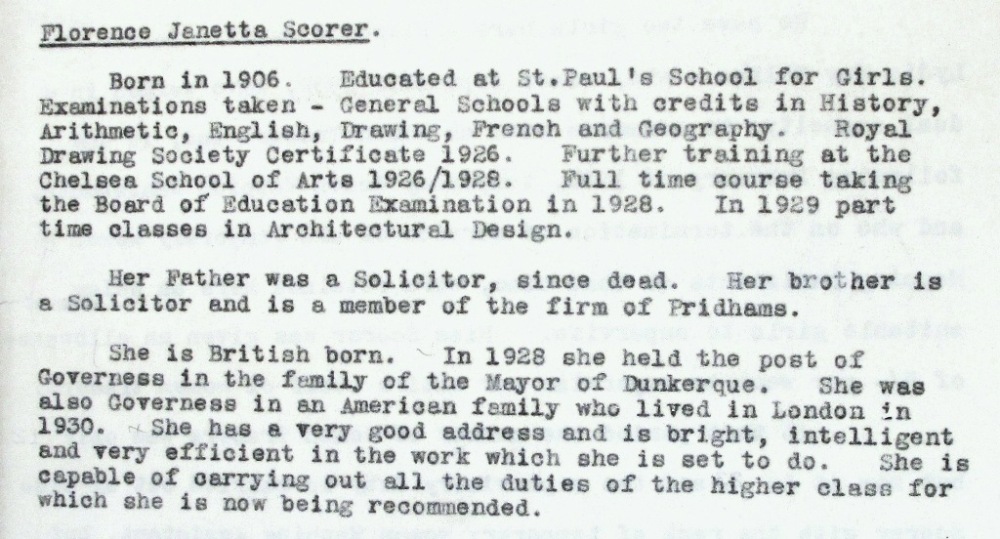

Like all the best stories – factual or fictional – ours has a heroine: Janetta Scorer. Reading through the files I learnt far more about Miss Scorer than we would normally expect the archives to reveal about an individual low-ranking employee.

Our tale begins on 9 January 1930, when a job advertisement appeared in the Daily Telegraph and the Morning Chronicle. To cope with an increase in demand for its services, the Land Registry had decided to recruit some young women to work in its mapping branch. This was a temporary measure, apparently inspired by the Admiralty’s successful deployment of female staff in similar roles.

Although the young women were employed as ‘tracers’, their jobs actually involved a variety of routine copying, colouring and indexing tasks, not just simple tracing. Employing a pool of temporary women tracers to cover these duties was supposed to allow the more highly-skilled male mapping assistants to concentrate on more complex or technical work.

Over the following months and years, however, the duties assigned to women tracers began to overlap with those of the mapping assistants. Some tracers were even promoted to the status of temporary women mapping assistants, in a two-year trial that began in July 1930.

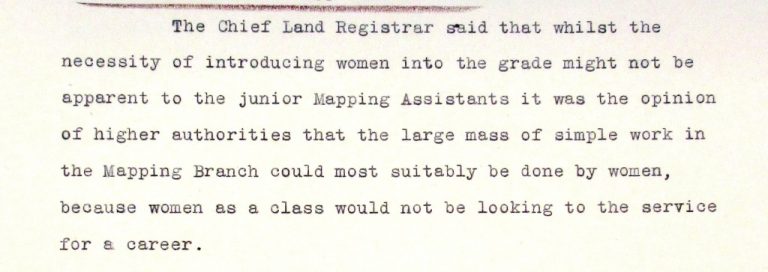

Not all of the male staff appreciated the presence of women in their workplace. Some junior mapping assistants appear to have felt threatened by the competition. The Chief Land Registrar brushed aside their concerns with the remark that ‘Women were competing with men in all professions and they must be prepared for women in the Mapping Branch.’ [ref] 4. LAR 1/156, minutes of meeting on 27 January 1931. [/ref]

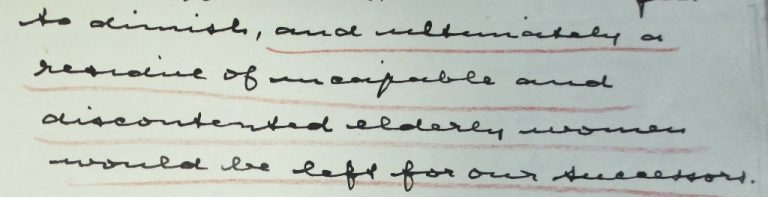

‘… and ultimately a residue of incapable and discontented elderly women would be left for our successors.’ A middle manager argues against allowing women to take up permanent jobs as mapping assistants. Catalogue reference: LAR 1/155, note dated 14 January 1932.

Male managers within the Land Registry expressed mixed views on whether or not employing women had proved a success. Suggestions were made that female staff were less efficient or took too much sick leave but statistical evidence indicated otherwise.

Although young women were acknowledged to give good service in the workplace (at least prior to marriage), they were not really expected to want or pursue careers. At the same time, middle managers criticised some of the female mapping assistants for lacking sufficient drive and ambition to work in cartography at a higher level.

Promoting women tracers to fill mapping assistant vacancies was particularly controversial because this was seen primarily as a trainee role, best suited to bright, male school-leavers who would progress to higher things later. Nonetheless, it was accepted that certain ladies – including Janetta Scorer – had proved themselves to be at least as capable as the boys of doing this level of map work.

For a woman, working at the Land Registry in the 1930s was a job but not a career. Catalogue reference: LAR 1/156, minutes of meeting on 27 January 1931.

Miss Scorer enjoyed a successful stint as a temporary woman mapping assistant between February 1931 and July 1932, but she had to return to the tracing department when the flow of work reduced and the experiment of employing women in that role ended for the time being.

No suitable male employee could be found to supervise the tracers, so the capable Miss Scorer was recommended for the job. She accepted it, but she had to fight to be paid in line with her additional responsibilities.

At first, her immediate superiors – aided by Mr D’Arcy Little, Chief Assistant in the Establishment Branch [ref] 5. Mr Little was what we would now call a Human Resources Manager. [/ref] – secured her an allowance of five shillings extra per week. Not until April 1933 were she and her assistant, Lydia Welham, restored to the pay grade of women mapping assistants.

Miss Scorer continued to campaign for career progression possibilities for herself and her staff, all of whom were temporary employees, not permanent (or ‘established’) civil servants.

At that time, becoming a permanent mapping assistant normally involved passing written and practical exams. The upper age limit for sitting these was 18, a rule that denied virtually all tracers the chance of promotion and job security.

With the help of Mr Little, exceptions were made for Miss Scorer and Miss Welham, whose qualifications, aptitude and proven experience were more than equal to the demands of the work. [ref] 6. The fact that both were well brought-up young ladies who had been to good schools was also seen as a point in their favour. [/ref] Both were made permanent civil servants with the rank of women mapping assistants in July 1934. The other tracers were less fortunate: their duties did not give them the training or experience necessary to be able to do the jobs of mapping assistants.

Seen from the perspective of 2014, these events of 80-plus years ago seem like another world. Even though I was already aware that women had had to struggle hard to be offered jobs that were seen as entry-level when performed by men – and that the existence of separate male and female pay scales meant that they had to accept unequal pay for equal work – it was still a shock to see the evidence of this in the files.

It is unlikely that women such as Phyllis Pearsall and Janetta Scorer set out to smash any cartographic glass ceilings. Yet they became the forerunners of the many women who have created or worked with maps in diverse ways up to the present day. [ref] 7. For instance, these women who worked for the Edinburgh firm of John Bartholomew & Son in the 1960s. [/ref]

Needless to say, the historic maps held here at The National Archives are well used and appreciated by people of both sexes equally. Any other situation is, thankfully, unimaginable.

An interesting piece of Social History in relation to job/career development of women. Working and learning’on the job’ has rarely attracted ‘in house provision’ for courses. Using the upper age limit at 18 excluded older employees coming into a skill later in life. There is room in balanced HR planning for both today; therefore lessons to be learned from this archive.

Thank you for your comment, Charles. I’m glad that you found my post interesting.

I thoroughly agree with your point about how learning from past experiences (as recorded in the archives) can help us in the present and the future, as well as showing us how much (or in some cases how little) has changed in the intervening years.