On 10 May 1976, Jeremy Thorpe resigned as leader of the Liberal Party. Despite helping to revitalise the Liberals, his decision to step down did not come as a shock. Thorpe had for some time been dogged by rumours surrounding his personal life. By the time of his resignation, he was facing allegations of engaging in ‘homosexual acts’ – before they were decriminalised by the Sexual Offences Act 1967 – and involvement in a plot to murder his alleged former lover. The scandal was yet to reach its height, however, and Thorpe continued as Liberal spokesman on foreign affairs under his eventual successor, David Steel.

Jeremy Thorpe was born in London in April 1929. His father, John, had been a Conservative MP, as had his maternal grandfather, Sir John Norton-Griffiths, or ‘Empire Jack’. After wartime evacuation to the United States, Jeremy was educated at Eton and then Trinity College, Oxford. Here the charismatic Thorpe became head of the Liberal Club, the Law Society and finally the Union. After practising law and working to reduce the Conservative majority in his adopted North Devon seat, he was narrowly elected to Parliament in 1959 at the age of 30.

Thorpe’s election as Liberal leader came in January 1967. His leadership did not begin well, and the 1970 election saw the Liberals return just six MPs, down from 12 in 1966. Just weeks later, personal tragedy struck when Thorpe’s wife Caroline was killed in a car crash.

Britain was in the midst of industrial disputes when Conservative prime minister Edward Heath called the next general election. The February 1974 poll saw the Liberals nearly treble their vote, but the nature of the electoral system saw this translate to just 14 seats. The result was a hung parliament. Labour became the largest party. Facing the end of his premiership, Heath offered Thorpe a senior Cabinet post in exchange for Liberal support of the government. Thorpe, however, was unwilling to agree to a coalition without electoral reform, and Heath resigned as prime minister.

The scandal surrounding Thorpe originated in the early 1960s. He met Norman Josiffe, later known as Norman Scott, a stable boy and part-time model, and the two men established a relationship. The exact nature of this is contested. According to Scott’s account, it was sexual at a time when ‘homosexual acts’ were still illegal in the UK. Despite receiving assistance from Thorpe, Scott was convinced that he had been wronged. He subsequently sought ways to publicise the relationship.

Becoming increasingly concerned, Thorpe eventually confided in fellow Liberal MP Peter Bessell and allegedly came up with various schemes to rid himself of Scott for good. One plan supposedly involved luring Scott to the Florida Everglades, murdering him, and feeding his body to alligators.[ref]1. Dominic Sandbrook, ‘Seasons in the Sun: The Battle for Britain, 1974–1979’ (London: Allen Lane, 2012), p. 444.[/ref]

More concrete plans against Scott allegedly began to form in the aftermath of the February 1974 election, and culminated in October 1975. Masquerading as a friend, Andrew Newton, a former pilot, drove Scott and his Great Dane, Rinka, out to Exmoor. He stopped the car and all three exited the vehicle. Newton, who was scared of dogs, panicked and shot Rinka in the head. The gun then jammed. Scott survived and his allegations finally became public during his trial for social security fraud early the following year.

The political impact of the scandal was far-reaching. Prime minister Harold Wilson had become increasingly suspicious of South Africa, which was the subject of international censure due to its government’s policy of apartheid. During a House of Commons exchange regarding the United Nations on 9 March 1976, Wilson stated that:

‘I have no doubt at all that there is strong South African participation in recent activities relating to the right hon. Gentleman the Leader of the Liberal Party’.

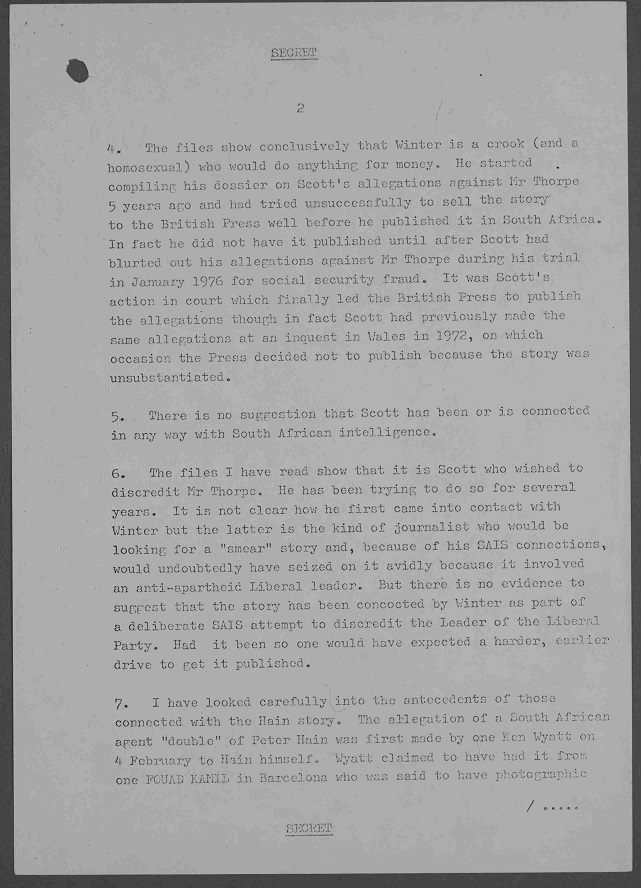

He did add, however, that there was no evidence that this extended to the South African government. Wilson’s suspicions led to the commissioning of a report by the Intelligence Coordinator in the Cabinet Office, Sir Leonard Hooper. This concluded that:

‘there is no evidence to suggest that the story has been concocted … as part of a deliberate SAIS [South African Intelligence Services] attempt to discredit the leader of the Liberal Party’ (PREM 11/2236).

According to Wilson’s principal private secretary, the prime minister was ‘convinced that Scott was being used by the South African State Security Organisation’ as a means to ‘destroy political leaders in this country’ (PREM 11/2237). Wilson’s personal interest in the affair also led him to acquire a copy of Scott’s social security file (PREM 11/2236).

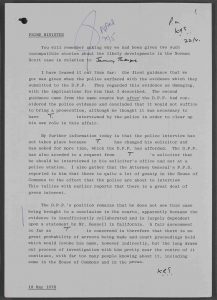

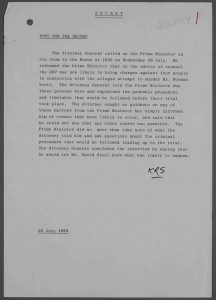

As late as May 1978 the director of public prosecutions (DPP) still doubted whether there was sufficient evidence to bring charges against Thorpe. On 26 July, however, the attorney general informed James Callaghan, who had succeeded Wilson as prime minister in April 1976, that the DPP was likely to bring charges against four people for conspiracy to murder Norman Scott. The men were formally charged on 3 August. Meanwhile, there was some concern within Downing Street at media suggestions that the Liberal Party was seeking to have the trial postponed until after the election in order to avoid further damage to their prospects (PREM 11/2238).

- An update for the prime minister on the likelihood of Thorpe being prosecuted (catalogue reference: PREM 11/2237)

- An account of the meeting at which the attorney general informed James Callaghan that charges would be brought (catalogue reference: PREM 11/2237)

The trial of Jeremy Thorpe and three others for conspiracy to murder Scott began at the Old Bailey on 8 May 1979. Bessell testified against Thorpe in exchange for immunity from prosecution, while Thorpe decided not to give evidence in his own defence. After six weeks, the four accused were found not guilty. Director of Public Prosecutions files on the case (DPP 2/6542–6571) remain closed until 2039. Files regarding the case against Andrew Newton (DPP 2/6008–10) and a separate attempt at bribery to obtain confidential information regarding Thorpe (DPP 2/6715) are currently scheduled for release two years later.

Aspects of the trial led to increased scrutiny of the press. The nature of the arrangement between Bessell and the Sunday Telegraph effectively provided a financial incentive for a guilty verdict. The newspaper promised Bessell £50,000 for the serialisation of his memoirs, but only £25,000 for shorter articles should legal issues prevent the book from appearing. Lord (Basil) Wigoder launched a Private Member’s Bill opposing payments to witnesses that were dependent on a trial’s outcome. After debate during the second reading of the Dealings with Witnesses Bill on 16 July 1979, the proposed legislation was withdrawn. The Press Council eventually reprimanded the Sunday Telegraph in October (HO 342/215).

The 1979 general election took place just five days before the trial got underway. Jeremy Thorpe stood once again for his North Devon constituency. He lost just 5,000 votes, but this was enough to hand victory to the Conservative candidate. He did at least finish ahead of his long-time antagonist, the journalist Auberon Waugh, who received 79 votes for the Dog Lovers’ Party.

The result was to mark the end of Thorpe’s political career. Keen to ensure that no further negative publicity was brought to bear upon the party, David Steel fought against those who wanted pursue their former leader for £10,000 of party funds that had been used in dealings with Scott. ‘I, in turn’, Steel wrote in a Guardian obituary for Thorpe, ‘promised that Thorpe would play no further part in the public life of the party’. He died in December 2014 after a long battle with Parkinson’s Disease.

Thanks for the share

Nice post.