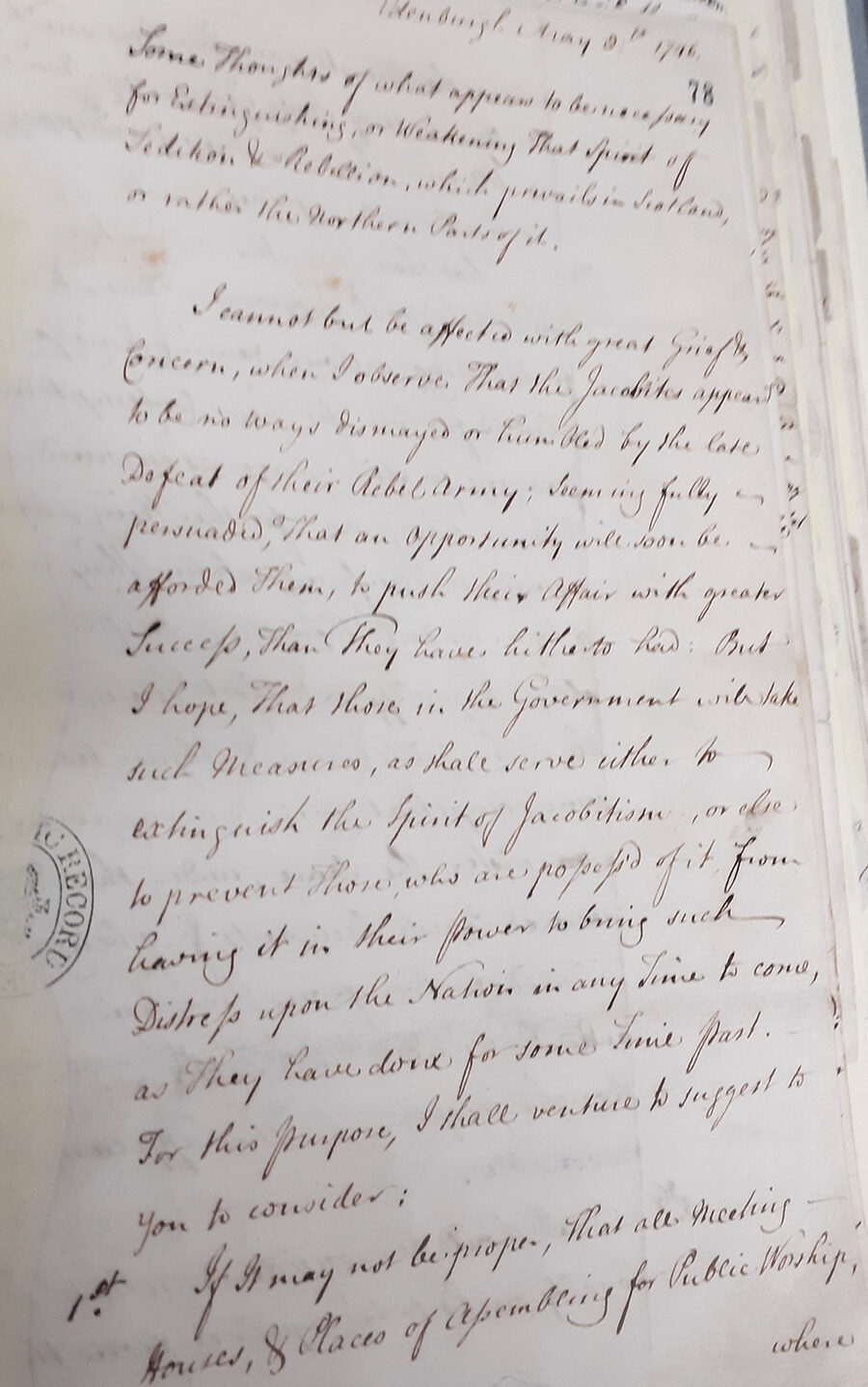

To coincide with March’s Women’s History Month, I highlight records associated with a somewhat forgotten Jacobite, ‘Bonnie Jeannie’ Cameron. Having first encountered this celebrated 18th century historical figure during my recently completed SP 36 ‘State Papers Domestic, George II’ volunteers cataloguing project; that undertaking afforded me the opportunity to focus on her eventful life.

Jean Cameron of Glendessary (c.1698-1772) was a member of the Scottish Highland gentry and a Jacobite supporter of the exiled House of Stuart. Although few details of her life can be established as fact, it was said that she had married an Irish army officer in French service called O’Neil, but the marriage was a failure as she returned home to her family estates in Scotland.

While her father Hugh Cameron of Morvern had been active in the failed Jacobite rebellion of 1715 (see footnote 1), she may have been briefly involved in the far more threatening rising of 1745 (see footnote 2), during which the Stuart heir Charles Edward (‘Bonnie Prince Charlie’) attempted to claim the British throne for his father James Francis Edward (the ‘Old Pretender’), and marched as far southwards as Derby, a little over 100 miles away from the relatively undefended London.

As ‘Jenny Cameron’, she became well-known as something of a celebrity after a number of sensationalised accounts of her life and deeds during the Forty-five Rebellion were published (see footnote 3). The majority were almost entirely fictional, and some were intended by the ruling Hanoverian dynasty to act as anti-Stuart propaganda. However, she was a lifelong devoted Jacobite, and her fame commenced when she reputedly single-handedly recruited 300 of her clansmen, and accompanied them in time for the raising of the Stuart standard at Glenfinnan in the western Highlands on 19 August 1745. As factor of the family estates for her ailing elder brother (John Cameron) at Loch Arkaig, there is no evidence that she was actually involved in any action, or even met the prince in person.

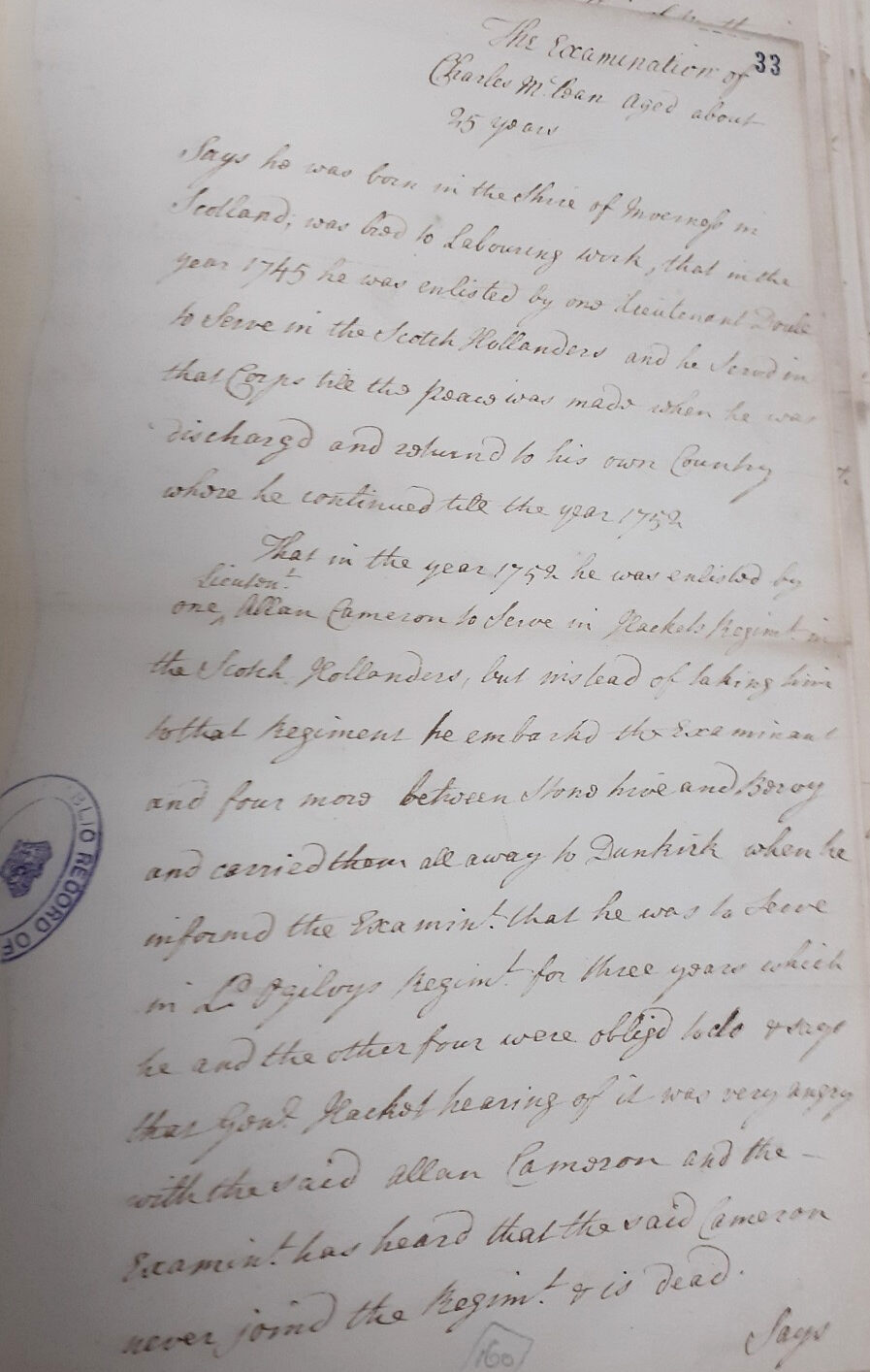

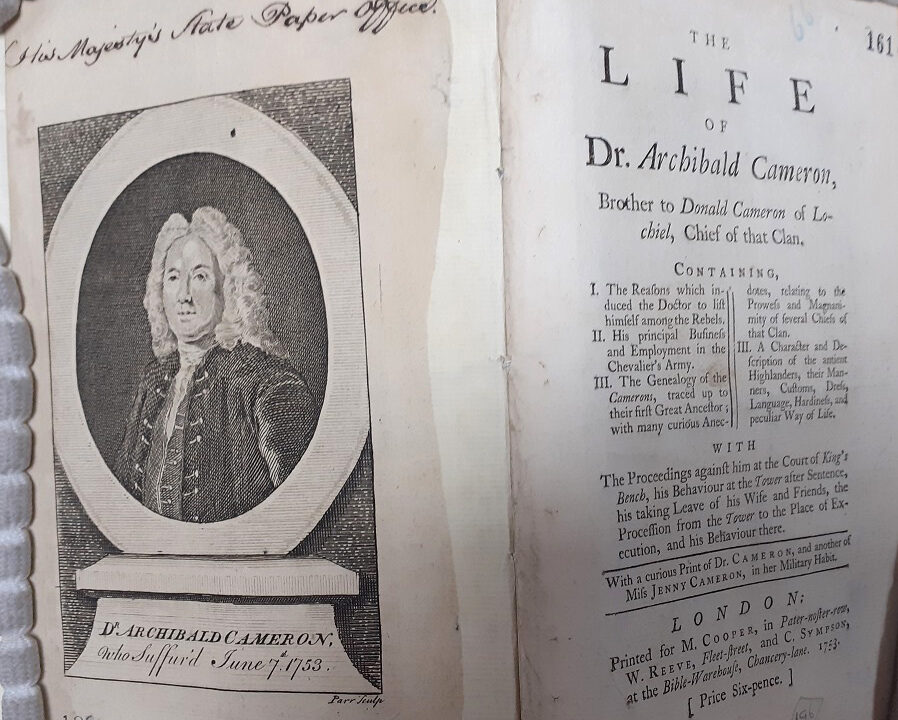

Jean was both connected with the ‘senior’ family-line of Cameron of Lochiel, hereditary chiefs of Clan Cameron, its leader Donald Cameron (the ‘Gentle Lochiel’) playing a significant military role in the ensuing rebellion, and with Doctor Archibald Cameron (her cousin), who ran a notorious Jacobite spy network which operated between Paris, Amsterdam, and Scotland. Her younger brother Allan, moreover, held a commission in the French army, and as a career soldier would serve the Bourbon monarchy into the 1750s (before hostilities broke out once more in mainland Europe).

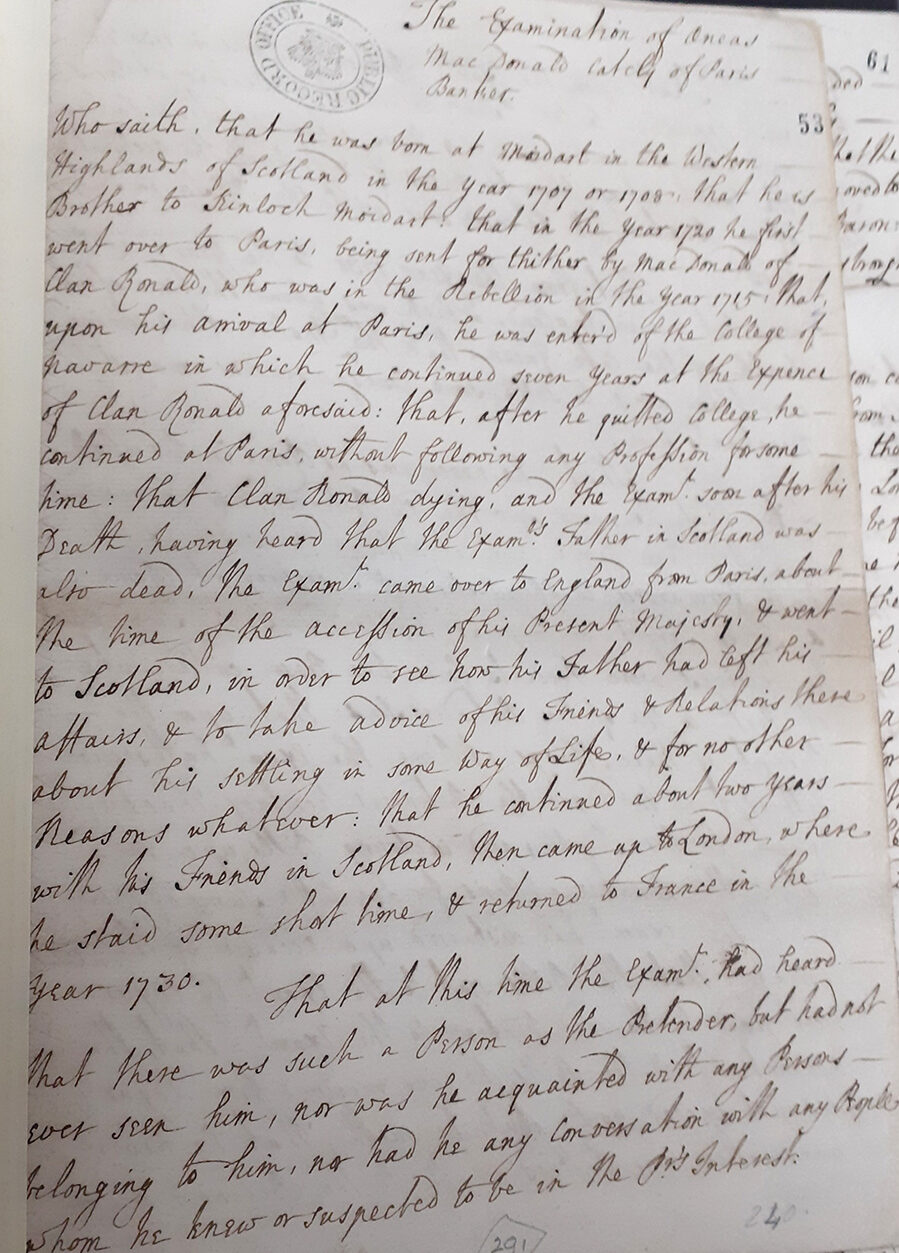

Although ‘Jenny’ may subsequently have attended the Jacobite Court at Holyrood House, Edinburgh during the six weeks that the city was occupied by the prince’s forces, and despite sending some cattle to Charles’s army, she took little part in the rising itself. However, what is certain is that she was at Glenfinnan, as the Franco-Scots banker Aeneas MacDonald who was also present at the mustering of the clans (and later captured after Culloden) described her as ‘[…] a genteel […] woman, […] with hair as black as jet’ (see footnote 4).

Despite her rather peripheral involvement, a number of cruel and somewhat doubtful accounts were later circulated in England portraying Jenny either as an active martial leader, an ‘amazon’ marching at the head of her clan (who was personally responsible for the rout of Sir John Cope’s forces at the Battle of Prestonpans in September 1745), or as a ‘lewd woman’ who was Charles’s mistress (see footnote 5).

Though largely untrue, such fanciful stories were intended to de-legitimise the Stuart cause by identifying it as a party of disarray by suggesting that its leaders were cowardly, and morally bankrupt. Their popularity was to give rise to songs, picaresque novels and even a play, and by 1750 ‘Jenny Cameron’ herself was a living legend, although, at the cost of her good reputation. Furthermore, in 1746 a musical play by the baroque composer Thomas Augustine Arne (see footnote 6) was performed at Drury Lane called ‘Harlequin Incendiary or Columbine Cameron’, while the scandalous The Life of Miss Jenny Cameron, The Reputed Mistress of the Deputy Pretender was published by the Lowland Scottish Whig Archibald Arbuthnot in that very same year.

Intriguingly, were there three Jacobite Jenny Camerons, or was this just one person who was intentionally linked to events to darken her good name? The truth about Jean Cameron’s involvement in the ’45 is thus further confused by women with the same name who were thought by the authorities to be her.

Another woman called Jean or Jenny Cameron was taken prisoner at Stirling in early 1746 by government troops, who claimed in fact to be a milliner from Edinburgh, whom the Hanoverian army’s commander-in-chief, William Duke of Cumberland, recommended (to the Secretary of State, the Duke of Newcastle) to be imprisoned in Edinburgh Castle.

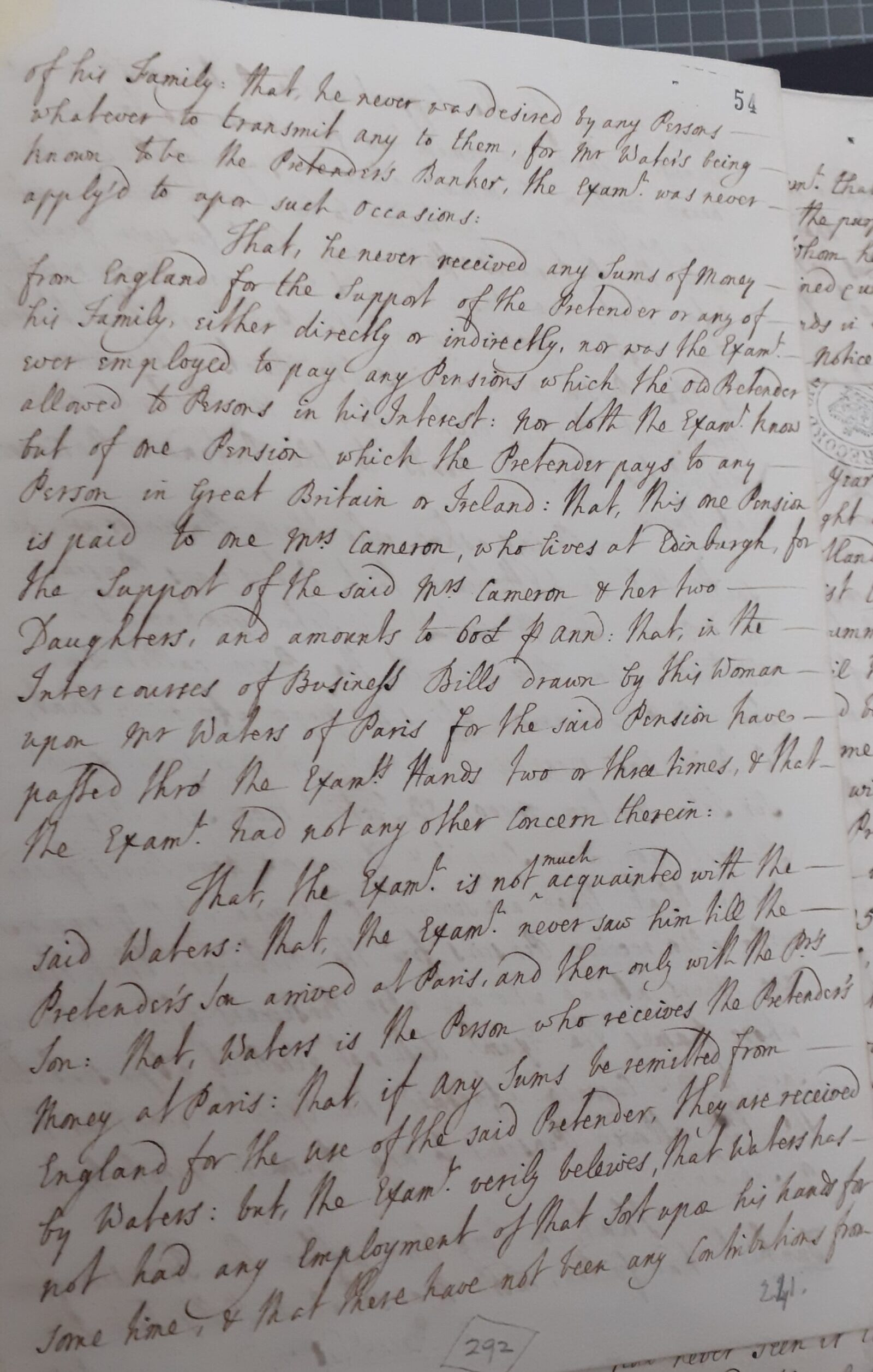

It is believed that this Jenny (and her two daughters) was in receipt of a pension from the Pretender at the time of her arrest, and who would long after revel in her association with the Bonnie Prince’s cause. Conversely, another Jacobite adherent, Lady Margaret Ogilvy, who had accompanied her husband (Lord David) on the advance into England, actually managed to escape from Edinburgh Castle to France, but despite her attainder returned to Scotland to give birth to a child and secure their inheritance (see SP 54/34/30c, SP 54/41/21, and SP 54/41/30).

Yet another woman who was also active in 1745 was a certain Jenny Cameron who went to the émigré Stuart Court at the Palazzo Muti in Rome, to petition the exiled James VIII for a pension in the latter 1750s. She may well have been the widow of (Doctor) Archibald Cameron, the younger brother of Lochiel, who was the last Jacobite to be executed in 1753 for his involvement in the Elibank Plot (see footnote 7).

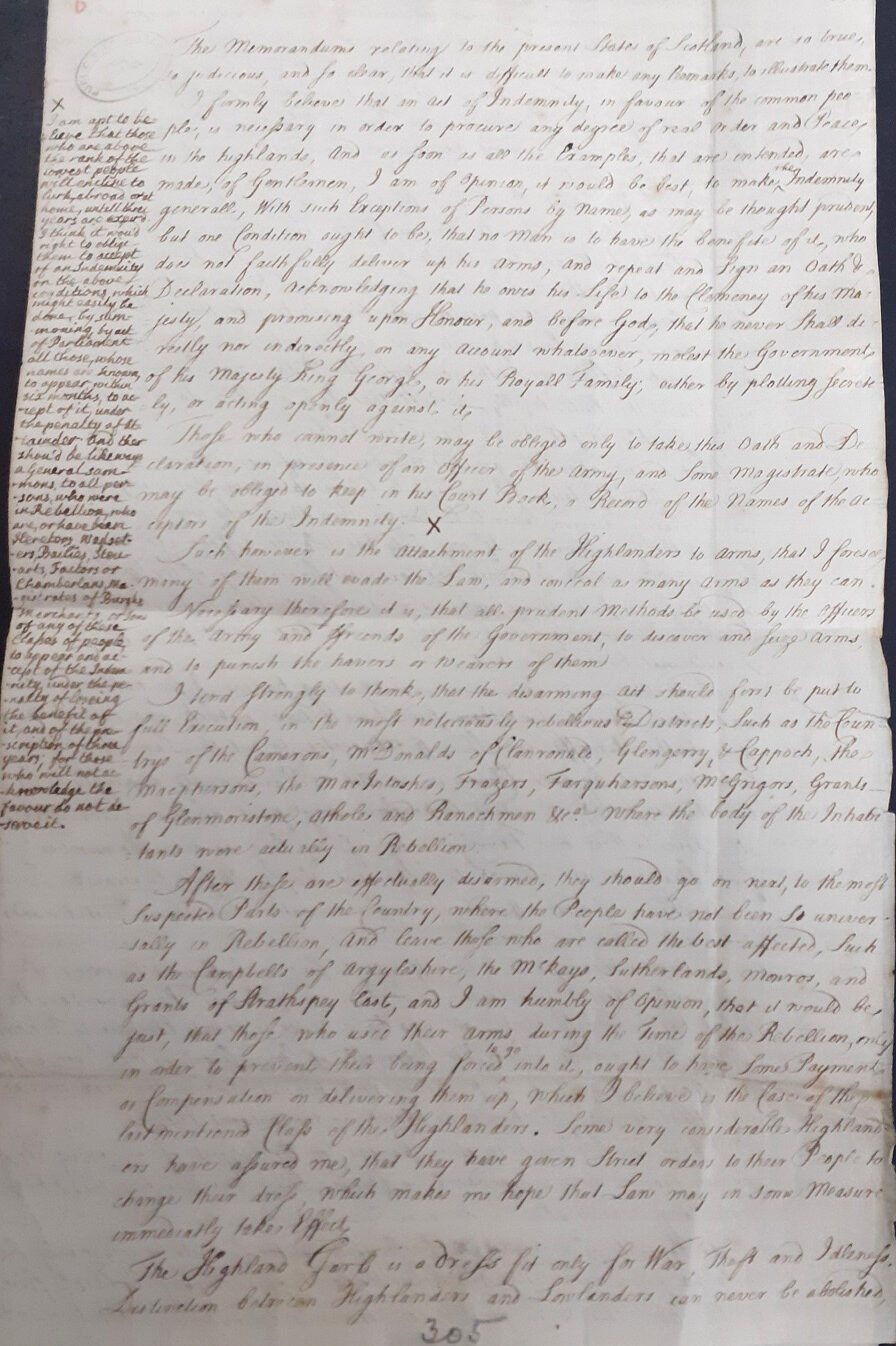

After the bloody treatment of the defeated Jacobite army on Culloden Moor by Cumberland’s forces in April 1746, the Cameron tenants suffered from punitive actions by government militias (both Highland Independent Companies, and Campbell militia), although the Glendessary family seem to have retained most of their property.

In 1751 Jean purchased isolated estates in the Central Lowlands to escape the brutal suppression of the Highlands. She is said to have lived a quiet and devout existence at Blacklaw in South Lanarkshire, and to have been locally popular (see footnote 8). Cameron herself returned to relative obscurity following the 1746 Act of Proscription which sought to destroy the Gaelic cultural way of life (see footnote 9), never fully trusted or really forgiven by the government, she was ‘watched’ by their agents as late as 1753.

While women clearly played a vital role during the ’45 campaign (many suffering terribly at the hands of a vengeful government army), some Jacobite women enjoyed a freedom of expression which allowed them to air their opinions with great frankness (see footnote 10), motivating the Jacobite forces, with recruitment, providing resources, or carrying out individual acts of bravery. Though Jeannie Cameron for her part was ultimately a somewhat shadowy ambiguous character, she was undoubtedly a very loyal and capable individual. I duly honour her memory.

Footnotes

- The number of recruits to the Jacobite armies in Britain was far higher in 1715 than in 1745. This support was not just from the Stuart’s traditional heartland of Scotland, but from northern England too, and all sections of society. Jonathan Oates, The Last Battle on English Soil, Preston 1715 (Ashgate, 2015, p.2).

- With an army that at its peak (before the victory of Falkirk in January 1746) never numbered more than 8,000 strong.

- W Drummond-Norie (March 1897). ‘Jenny Cameron’. Celtic Monthly. 5: 115. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- Robert Chambers, History of the Rebellion 1745-46 (1847, p.215).

- Carine Martin (2015) ‘Female Rebels: the Female Figure in Anti-Jacobite Propaganda, in Macinnes (ed) Living with Jacobitism, 1690-1788 (Pickering and Chato, p.86).

- As a leading Georgian theatre composer, Arne is best-known for his patriotic song ‘Rule Britannia’, and his association with the anti-Jacobite ‘anthem’ ‘God save our lord the king’.

- Masterminded by Alexander Murray of Elibank during 1752-53, the desperate conspirators planned to kidnap George II and the Hanoverian royal family in London.

- Although a Catholic herself, she generously endowed the local Presbyterian Church school. Ewan Innes, Reynolds and Pipes (eds) (2007), Biographical Dictionary of Scottish Women (University of Edinburgh Press, pp.59-60).

- Re-establishing the Disarming Act of 1716, the legislation of 1 August 1746, was part of a series of efforts to assimilate the Scottish Highlands, ending their ability to revolt, and the first of the ‘King’s laws’ that sought to crush the clan system.

- Cùil Lodair Culloden, Lyndsey Bowditch (The National Trust for Scotland, 2011, p.34).

Hi there,

Jean Cameron was the daughter of Allan Cameron, of Glendessary, and Christian Cameron, the daughter of Ewen Cameron, 17th Chief.

Other then that, the facts fit with Jean Cameron of Glendessary.

Secondly, I believe the picture painted by Allan Ramsay is her. I am a Cameron ancestor, and she resembles me quite a bit.

Take care.

I confirm too that Jean Cameron was the daughter of Allan Cameron, 3rd of Glendessary, and Christian Cameron, daughter of Sir Ewan Cameron of Lochiel.

Paradoxically, the Camerons of Glendessary had no connection with Glen Dessary to the west of Loch Arkaig. They never lived there – and they never held any land or property there. Home for the family was in Acharn, Morvern – some 30 miles to the south west of Glen Dessary. At the time of the 1745 Rebellion, Jean Cameron was residing in Strontian – on the north side of Loch Sunart.

Jean was arrested by the Government Forces in February 1746, and incarcerated in Stirling Prison.She petitioned for her release in July 1746 (NLS/17518/76), and gained her freedom in November of that year.

Although the interesting blog does not mention it, I am sure you are aware that the subject of the identity of Jean Cameron and the confusion between the multiple people bearing the name, has been the subject of published research in academic print, books, and the more refined newspaper articles. There is an extensive bibliography, and it is a shame the ‘story’ of the three Jeans/Jennies is not more well known. She is well-known in some areas, no less East Kilbride, where the Glen Dessary figure lived at Blacklaw (later called Mount Cameron).

This academic topic received especial focus in the early 1900s and 1980s-90s. Most later content, such as the DNB, recapitulates that content. The dialectic of the corpus of research aligns with what you describe overall and provides nuance on certain aspects. What you reveal about the Mrs Cameron of Edinburgh being suspected of receiving a pension from the Prince, helps to flesh out the reality behind the fame she enjoyed in her later old age in the capital. That Jean/Jenny died in poverty, apparently living in a mere ‘stairfit’ (stair foot) of an Edinburgh close.

It is the third Jean Cameron who is of significant interest. In addition to being imprisoned, she also appears in a number of Broadsides of the period, which indulge in quite lewd/sexualised content. This appears to be the origins of the reputation which was so infamously applied to Jean Cameron of Glen Dessary. Of course they were two separate people. This other Jean/Jenny Cameron was obscure and died in the Low Countries. I think the developments here between your research and my own is that the Edinburgh Jean was more than a pretend mistress and did possibly have some association with the Prince, and that the third Jenny was possibly quite a scandalous figure, although obscure. Irrespective of confusion between the two figures, it is true that this third Jenny may or may not have suffered the same Whig propaganda as did Jean of Glen Dessary.