The search for a person within The National Archives can sometimes yield a line or two about who they were and what they did, but for me, the enduring appeal of the MI5 files at Kew is the astonishing level of detail you can often glean from a Security Service report.

Today, biographers of the actor Michael Redgrave and the playwright JB Priestley, among others, will have a wealth of new material to pore over as their MI5 files are made public for the first time.

Files in the KV 2 series in particular, labelled Personal Files (PF) at the Security Service, can provide a lot more colour than most official sources, containing everything from transcripts of phone conversations, to intercepted letters and photographs.

Ivan Serov

Few people in the latest batch of Security Service files have a reputation as unsavoury as that of Ivan Serov. If you can tell a lot about somebody from the company they keep, this ‘devoted friend’ of Stalin and trusted lieutenant of Beria was clearly a man best avoided.

He was responsible for supervising – in the euphemistic language of the time – the ‘mass deportation’ and ‘purging’ of anti-Soviet elements across the Baltic States, Ukraine and Poland as a result of which many hundreds of thousands were killed.

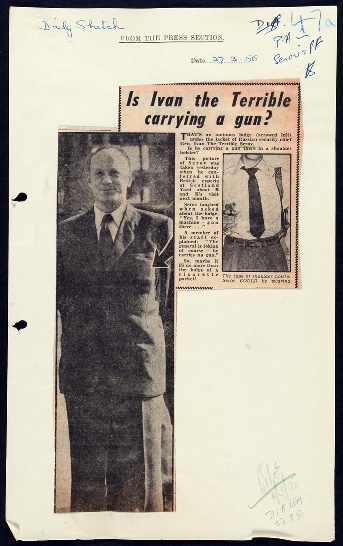

The two files on Serov released today focus on his 1956 trip to Britain, as part of an advance party charged with making the security arrangements ahead of the visit of Nikita Khrushchev later that year. The British press dubbed him ‘Ivan the terrible’, ‘the executioner’ and the Kremlin’s ‘hatchet man’ and his presence was deeply resented by the refugee communities from Eastern Europe who had made their home in Britain after the war.

What make the files so extraordinary are the personal details we are given about a man who appears almost as a comic-book villain (although there was nothing funny about his crimes).

We learn for instance that he was something of ‘a ladies’ man’ who was ‘good mannered, carefully dressed and a moderate drinker’ – although this doesn’t quite tally with the experience of one British official charged with meeting Serov at the Russian Ambassador’s residence.

‘Serov promptly invited me to prove my expertise in vodka and suggested that we should test it to see if it was the real Moscow stuff or whether the ambassador was trying to palm off something inferior on us, since ambassadors were notoriously unreliable people.’

We get a sense of what sort of company he was.

‘His sense of humour is somewhat heavy, and his jokes are of the heavy sarcasm variety‘ reads one report.

While another adds that: ‘Serov told a couple of strongly anti-Semitic jokes, which were well received, not the least by himself’.

His vanity was ‘considerable’, but this ‘tough wiry little man’ was also acutely conscious of his ‘lack of inches’ – which may explain the ‘very thick soles’ on his shoes.

On a long car journey down to Portsmouth, Serov opened up, telling his life-story and talking expansively on a range of topics. He told his British hosts that he was just ‘a simple peasant’ who liked saying what he thought even if people were offended. Indeed, he was remarkably candid, discussing everything from his son to the Soviet leadership, and we can only speculate that anything he said would have been carefully thought through beforehand. He was, after all, the only man in Soviet history to have headed up both the political intelligence agency (KGB) and the military intelligence agency (GRU).

The Grand National and Sherlock Holmes

Serov was full of praise for his hosts, proclaiming ‘complete trust’ in British security arrangements, but denouncing the Americans as ‘naïve’ and the French and Italians as ‘degenerate’.

A keen sportsman, who listed skiing, skating and horse-riding among his hobbies, he is said to have remarked that ‘the Russians admired British sportsmanship and particularly our ability to be good losers’ – a backhanded compliment if ever there was one. He went on:

‘Games with the British were always clean whereas Canadians and Americans tried to provoke the Soviet sportsmen. At Cortina (which hosted the 1956 Winter Olympics) the Soviet Ice Hockey players were ordered not to lose their tempers in spite of every provocation. After all the Russians liked a fight as much as anybody but had they joined in a fight during the Olympics they would have been labelled as hooligans by the press.’

The tale is heavy with irony. Later that year the USSR and Hungary were to violently clash during a water polo game at the Summer Olympics in Melbourne, known ever after as ‘the blood in the water’ match. The match was the sporting spill-over from the Soviet Union’s crushing of the Hungarian revolution of 1956 in which Serov himself had played a part.

Other aspects of British culture seemed to intrigue him. He was disappointed to miss the Grand National and apparently ‘displayed a considerable familiarity with detective fiction such as Sherlock Holmes’. At lunch he even ordered one of his underlings to ‘make notes of the best British drinks and dishes for the benefit of the Soviet leaders’.

But the image of amiability he presented masked a ‘cunning mind’ and the Security Service assessed him as ‘a capable organiser who is completely ruthless with the cruelty of a Spanish inquisitor rather than that of a sadist‘.

I have to say, turning over his handwritten landing card in my hands, which lists his occupation as ‘chief of police’, was enough to give me chills.