Looking at historical records gives us the opportunity to see how different things were in the relatively recent past, and that is what we see when looking at government records from 1980.

In the summer of 1980, the British Lions went on tour to South Africa. The British Lions (now British and Irish Lions) are a team of rugby union players from the national sides of England, Ireland, Scotland and Wales, so selecting a squad and creating cohesion between them is always an art. In 1980 there was additional pressure to perform well and match the unprecedented success of the Lions’ last appearance in South Africa in 1974, when the Lions had won 21 out of 22 matches.

This was also a moment of deeply controversial debate over the role of international sport in either strengthening or weakening the racial divisions of apartheid. The records held at The National Archives show how the effects of the Lions’ decision to tour South Africa and play racially-segregated teams rippled across a variety of parts of British governmental business. Documents connect the 1980 tour to disputes on a range of topics from the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan[ref]British Embassy, Capetown to the FCO, January 9 1980, FCO 105/525.[/ref], to domestic relationships in the Thatcher household where ‘opinions … over the rugby tour [did] not coincide’[ref]HC Deb 17 January 1980 vol 976 cc1864-71 quoted in FCO to the British High Commissioner, Lagos, March 26 1980, FCO 105/526.[/ref]. As the British Chargé d’Affaires in Cape Town had said in 1974, ‘It’s only a game? Nothing could be further from the truth …'[ref]Diplomatic Report No. 322/74, FCO 160/163/7.[/ref]

In 1980, after decades of struggle, racial tensions in South Africa were high. In May 1980, two children were shot by Cape Town police during a protest by school students. This incident fuelled increased anti-apartheid feeling around the globe, and raised the issue about why the Lions would agree to a South African tour.

In 1977, the then British Prime Minister James Callaghan along with other Commonwealth Heads of Government had signed the Gleneagles Agreement, in which those leaders agreed to ‘withholding any form of support for, and by taking every practical step to discourage contact or competition by their nationals with sporting organisations, teams or sportsmen from South Africa or from any other country where sports are organised on the basis of race, colour or ethnic origin’[ref]Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting, London, 8-15 June 1977, Final communique. https://library.commonwealth.int/Library/Catalogues/Controls/Download.aspx?id=2297.[/ref]. As a result, the statement proposed ‘there were unlikely to be future sporting contacts of any significance between Commonwealth countries or their nationals and South Africa while that country continues to pursue the detestable policy of apartheid’. The Lions’ decision to go ahead with their 1980 visit to South Africa was, therefore, politically embarrassing.

Ahead of the tour British diplomats and politicians received demands that the UK find ways to prevent the Lions’ tour from taking place. The Foreign Office file FCO 105/525 contains messages from the Tanzanian and Liberian governments and from the poet and Senegalese president Léopold Senghor, who all insisted that the UK government take a firmer position[ref]President Léopold Senghor to Margaret Thatcher, February 26 1980, FCO 101/525.[/ref]. Australia was making similar pleas, worried that the Lions tour of South Africa would trigger a boycott of the 1982 Commonwealth Games in Brisbane by African and Caribbean teams.

The situation was so serious that the UK government even discussed the possibility of preventing the rugby players from leaving the country, although this was not really seen as an option. Removing the British Lions’ passports, the FCO stated, ‘would theoretically be possible’, but not practically[ref]FCO to the British High Commissioner, Lagos, March 26 1980, FCO 105/526.[/ref]. Such powers had ‘been used less than a dozen times since the War and always in direct support of the national interest’[ref]FCO to the British High Commissioner, Lagos, March 26 1980, FCO 105/526.[/ref]. It was decided that British citizens could not be prevented from acting as they choose, and that the Lions team could not legally be barred from touring.

The tour also had implications for discussions around sports funding in the UK. Other international authorities were asking that state funding be withdrawn from the activities of the Rugby Union. The head of the Supreme Council for Sport in Africa, Abraham Ordia, suggested this as an effective deterrent for the Lions team’s proposed tour[ref]FCO to the British High Commissioner, Lagos, March 26 1980, FCO 105/526.[/ref].

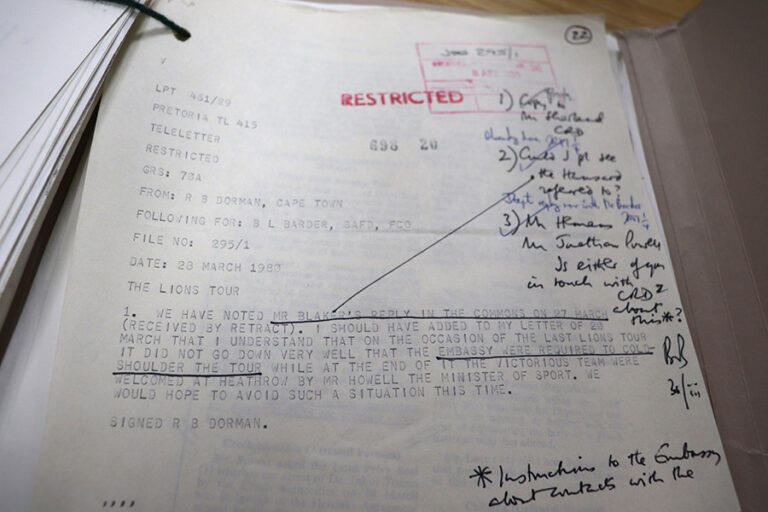

A final conversation emerged in relation to the position of the British embassy in South Africa. How were they to respond to the presence of the British Lions? Were they going to be expected to ‘cold shoulder’ the tour?[ref]British Embassy, Cape Town to the FCO, March 28, 1980 FCO 105/526.[/ref] Margaret Thatcher assured the House of Commons in March that the government would not provide embassy co-operation for the team, except for ‘normal consular assistance’[ref]British Embassy, Cape Town to the FCO, March 28, 1980 FCO 105/526.[/ref]. Yet that still left the Embassy with some doubts over expectations. Could they accept invitations to meet the team? And could they attend matches? Again, a further series of minutes and letters in the archives discuss this issue[ref]British Embassy, Cape Town to the FCO, March 20, 1980 FCO 105/526.[/ref]. How many members of embassy staff might reasonably attend a match in a single group before it looked as though the British embassy was giving its official blessing to the event? Eventually, it was decided, none[ref]FCO to British Embassy, Cape Town, April 21, 1980 FCO 105/526.[/ref].

In the end, although the 1980 British Lions tour went ahead, it was far from a sporting triumph. The team won all of their matches against local teams, but lost three of their four tests against the Springboks. The Lions didn’t travel to South Africa again until 1997, after the end of the apartheid regime. As reflected in the records of The National Archives, in the summer of 1980, when the Lions were at the centre of racial violence and diplomatic incidents, rugby and international politics have rarely been so entangled.

It should be borne in mind that Margaret Thatcher was against sanctions against South Africa even during its apartheid period and the suggestion of removing players’ passports were also considered for the Moscow Olympics in 1980. The British Lions were not the only team to tour South Africa, the New Zealand All Blacks had previously toured much against opposition.