Ellis Island immigration centre c. 1905. Via Wikimedia Commons, copyright expired: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AEllis_Island_in_1905.jpg

On this day 50 years ago, Ellis Island, the famous immigration point for many wishing to enter the United States, closed its doors for the final time. Today a vibrant museum and tourist destination, the island has been transformed from the reportedly intimidating and poor conditions experienced by thousands applying to enter the United States at New York between its years of operation, 1892 to 1954.

The story of Ellis Island is an interesting one to contemplate this week as we encourage people to Explore Your Archive. Ellis Island appears in our collection largely through the thousands of passenger lists (in series BT 27 and available to view online through Findmypast) of those going to New York during the period. These records are generally associated with family historians in the first instance, perhaps searching for the moment their family made the voyage to begin a new life, full of hope.

They are an interesting example of how to connect records in different collections, by comparing the outgoing passenger records we hold at The National Archives with incoming passenger records held by the Ellis Island foundation, which you can search online. However, as well as personal details of interest to family historians, the records also demonstrate the huge wealth of information available on population movement, in particular the levels of different nationalities, and the changes in numbers arriving at New York during and between the two world wars, for example.

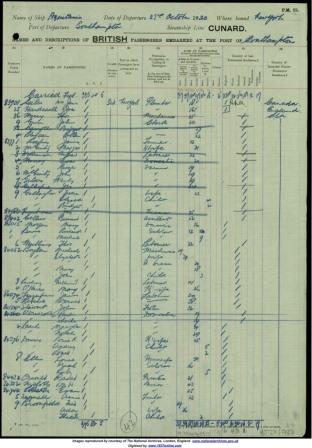

Outgoing passenger manifest of the Aquitania on 23rd October 1920, showing Fred, Ada and Theo Broomfield. Catalogue reference: BT 27/933

These records are of personal interest to me on both levels. In terms of family history, I have been able to trace the journey my great-grandparents made with their young child soon after the end of the First World War. Having visited the island myself earlier this year, I have caught a modern glimpse of what hundreds of thousands of people experienced on their first journey to America.

My great-grandfather Fred Broomfield served in and survived the First World War, then in October 1920 he is listed on an outgoing passenger list from Southampton with his wife Ada, and son Theo. Seven days later, they can be found on an incoming ‘Alien passengers for the United States’ manifest at New York. Consulting with colleagues, to the best of our knowledge Fred, Ada and Theo as steerage passengers would have passed through Ellis Island before setting foot in New York and continuing their onward journey to friends in Detroit.

The difference in information provided at the beginning and end of their journey is stark. In the outgoing list held here at The National Archives (and available to view online through Findmypast), information is scarce – name, status, age and country of residence are all you can decipher from the handwritten scrawl. However, on the incoming list at Ellis Island, perhaps unsurprisingly the amount of information gathered on immigrants to the United States is much greater. Ellis Island was principally set up to weed out ‘undesirables’ and therefore information on who was applying to pass into the United States was essential. [ref] 1. Jones, Maldwyn A. Destination America, 1976, London:Weidenfeld and Nicolson. p. 54. [/ref] From this manifest, I have descriptions of both Fred and Ada. I have Fred’s father’s name and address, their places of birth, whether they had money to their name, their intentions on arriving in the United States and the name and address of their contact in Detroit.

In particular, these Ellis Island documents are very useful for Irish migrant family history. Not only is immigration to the United States relatively high, the first surviving Irish census is from 1901 – a full 60 years after the first name-rich English and Welsh census. Therefore Ellis Island incoming documentation pre-1901 can provide the most detailed information available for many family historians of Irish migration. If you are carrying out research in the area, remember that as the biggest entry point for the United States, Ellis Island receives more publicity than perhaps other popular arrival ports. Boston, Philadelphia and even ports of Canada were all popular routes in to the United States, and so be sure to investigate where those leaving for North America were heading. In 1914 for example, of 1,218,480 immigrant aliens admitted to the United States, 878,052 passed through New York, leaving another 340,428 entering elsewhere. [ref] 2. Pitkin, Thomas Monroe. Keepers of the gate, 1975, New York: New York University Press. p. 111. [/ref]

As well as family history, the Broomfield family’s arrival in New York is an interesting point in the history of Ellis Island and migration. Prior to the war, Ellis Island had a bleak reputation as the ‘island of tears‘ due to the conditions on the island as a centre both of immigration and deportation, and the reported poor treatment of many. During the period of the First World War, as you might imagine, immigration levels dropped significantly. Comparing to the statistics above, in 1915, 178,416 immigrants passed through New York of a total 326,700 to the United States. By 1918, only 28,867 were admitted at New York. This gave a brief window of opportunity to improve conditions and the reputation of the Island. [ref] 3. Pitkin, Thomas Monroe. Keepers of the gate, 1975, New York: New York University Press. p. 111. [/ref]

However, Ellis Island was not only a passageway into New York, it was also a waiting point for those being deported – either turned away on arrival or deported at a later date. As the war continued and immigration levels dropped, boats to return deportees to their home ports were less available. Following the sinking of the Lusitania in 1915, the transportation of deportees to England and France was temporarily forbidden by President Wilson, putting increasing pressure on the facilities on the Island. [ref] 4. Pitkin, Thomas Monroe. Keepers of the gate, 1975, New York: New York University Press p. 114. [/ref] When Fred, Ada and Theo arrived in 1920, immigration numbers had begun to rise for the first time since 1914. New checks had been introduced in the interim, with literacy, medical and passport checks carried out on all passengers. By the end of 1920, immigration numbers were heading towards pre-war levels and the immigration station was struggling to cope processing the arrivals through the new lengthier systems.

As pressure increased, it turns out the Broomfield family arrived in New York just in time, as the Emergency Quota Act was passed in 1921, restricting immigration to 357,000 per year over the whole of the United States and individual percentage quotas for eligible nationalities. Following this, in 1924 immigration was restricted again through the National Origins Act, reducing the quota further to 150,000 per year and marking a permanent shift in United States immigration policy. Having been the key destination for immigration in the United States, Ellis Island went through significant changes over the following 30 years, slowly reducing its involvement in immigration to the United States. It finally closed in 1954 and lay derelict for many years before its reinvention as the thriving national monument it is today.

Ellis Island immigration hall today. Fred, Ada and Theo are likely to have passed through here. Image courtesy of Jenni Orme.

As for Fred, Ada and Theo, life in the United States didn’t fulfil the hopes of the early 1920s. In 1928, Ada, Theo and new arrival Wilfred can be found amongst records in BT 26 on the incoming passenger list returning from New York, but Fred, full of hope for a new life after the horrors of war, has not been heard of since… To find out more about how you can research those travelling to and from Ellis Island, see our research guide on Passengers.

The Ellis Island Foundation website also carries details of both crew on ships which docked in New York between 1892 and 1954. This is extremely useful for finding Merchant Seamen who were on the North Atlantic run. For example my great grandfather William Thomas Cronan, who was on the Olympic between 1920 and 1924 and on the Majestic in 1924, may be found in the manifests.