Jane Golding from the British Association for Local History explores how the census can be used to corroborate local history research. This post is part of 20sStreets, in which we explore local history stories in the 1921 Census, connecting people of the 2020s with people of the 1920s. Discover your own local history and enter our 20sStreets competition.

How often have you wished that you could go back in time, perhaps even only a few decades, in order to solve a particular historical conundrum? With no time machine in sight, comprehensive records from the period in question are surely the next best thing. For my home village, the record keeping activities of a local teacher offer a wonderful visual glimpse of several of its streets during the 1970s.

The village is Bishopstone, north Wiltshire (not to be confused with Bishopstone in the south of the county), and the record in question takes the form of two photographic albums where each entry is accompanied by a story about the past inhabitants of the property. Without a current local history society, care of the record books lies in the hands of a small number of interested villagers.

Whilst affording a valuable photographic record, the books surprisingly say very little about contemporary village life. The primary intention seems to have been to offer up an historical account. Here and there mention is made of taking pupils out of the classroom to visit older members of the community. We cannot say for sure how the information was gathered but there is little to suggest documentary sources played a role. The accounts were likely constructed for the most part from personal recollections.

Our enjoyment of the content of the village books is tempered by a recognition that we have a duty of care towards this wonderful legacy. Discussion to date has largely centred around how best to scan their pages to make the books more accessible and ongoing consideration of the preservation and curation of both the digital and physical copies. Beyond making an initial assessment of their overall value as a source of historical analysis, we had not yet examined individual entries in any detail.

Until last summer that is. When a tentative move towards a return to normal social activity forced us to take a more forensic approach to the village books. During a village-wide event, we used the material to create a walking history trail. A map guided visitors to temporary information boards positioned adjacent to key properties.

The stories in the books are rich and engaging and we could have used them directly but wishing to avoid perpetuating myth, we put their historical accuracy to the test. The 1920s were still within living memory when the stories were compiled and many of them relate to this period. So, when it came to corroborating detail from the village books against other sources, release of the 1921 Census earlier in the year gave us a huge boost, as the following record illustrates.

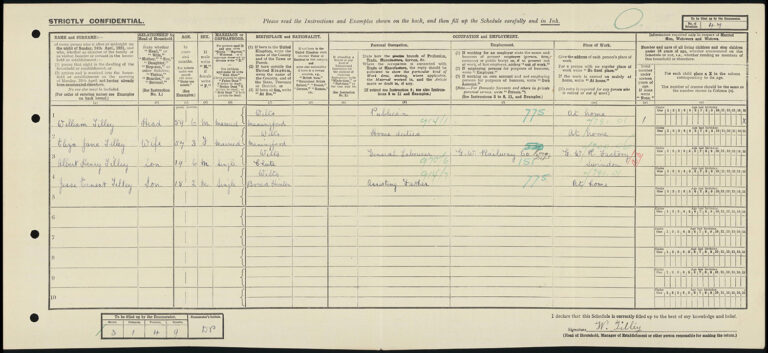

The village record book entry for the Royal Oak tells of how Mr William Tilley, the publican,

‘was out walking one day when he noticed smoke billowing up and hurried towards his home. A villager he met told him it was the Royal Oak, which shocked him so much he had a heart attack and was never well again after it.’

The entry continues to explain that the fire broke out in one of three thatched cottages to the rear of the property and, on spreading to its neighbours, caused substantial damage. Despite arrival at the scene by the Bishopstone Fire Engine, all three cottages were lost. Any structural remains had to be demolished but fortunately the Royal Oak itself was left unharmed.

The account gives no date, but an index search of the North Wilts Herald soon revealed that the fire took place on Tuesday 17th May 1927.[1] We were then able to turn to the 1921 Census for more information about the occupants of all four properties.

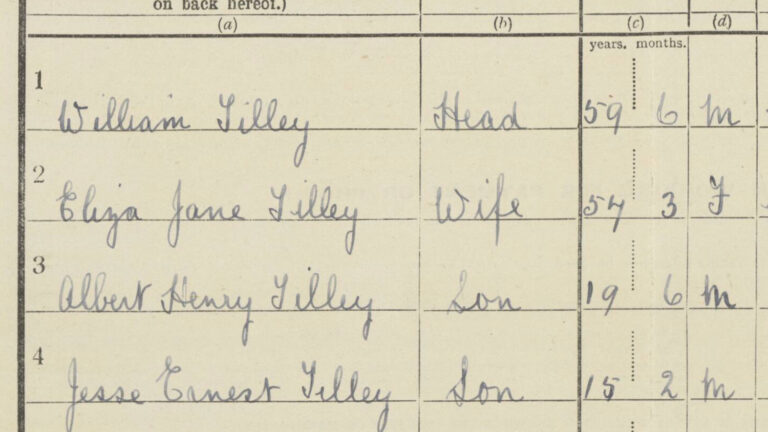

The Tilley family occupied the Royal Oak in 1921. At the time when the census was taken, William was 59 years old and would therefore have been in his mid-60s when out walking on that fateful day in 1927. Information from the 1921 Census also helped to verify details described by the author of the village books about the inhabitants of the three cottages to the rear of the pub. Not all the information tallies and further investigation is needed but it has enabled us to make confident use of material which otherwise may be doubted as hearsay.

The history trail was a great success and has generated wide interest among the present community. There is also a small but growing support for continuing the research and answer questions sparked by our initial dip into the 1921 Census. Albert Henry, the elder of William Tilley’s sons listed, is recorded as employed at the Great Western Railway Works in Swindon, some eight miles to the west of the village.

We have yet to analyse the returns to determine how many others were also making the same daily journey in 1921 and to gain an understanding of a changing rural community. Small beginnings but a hopeful start for a village currently without a local history society.

[1] 1927. A Bishopstone Fire. North Wilts Herald. 20 May. P.8c.

Very interesting use of the census material to explore the accuracy of the local history accounts.

The Old Meeting House Unitarian Chapel , built in 1702, recently had a Heritage Trail booklet reprinted. It was fascinating to hear living memory anecdotes as people went around the centre of Mansfield during Heritage Open Days following the route. Using the 1921 Census to verify the stories is something the heritage team could explore. Thank you.