This blog post will use ‘LGBTQ+’ and ‘queer’ as collective terms to describe people historically who were not cisgender or heterosexual. This post also uses umbrella terms to describe a variety of people from non-white backgrounds. Where possible more specific details are given, to address the diversity of past experiences.

These individuals would likely have used a variety of different language to describe themselves in their own lifetimes. For more context around language, refer to The National Archives’ guidance on Sexuality and gender identity history and Black British social and political history.

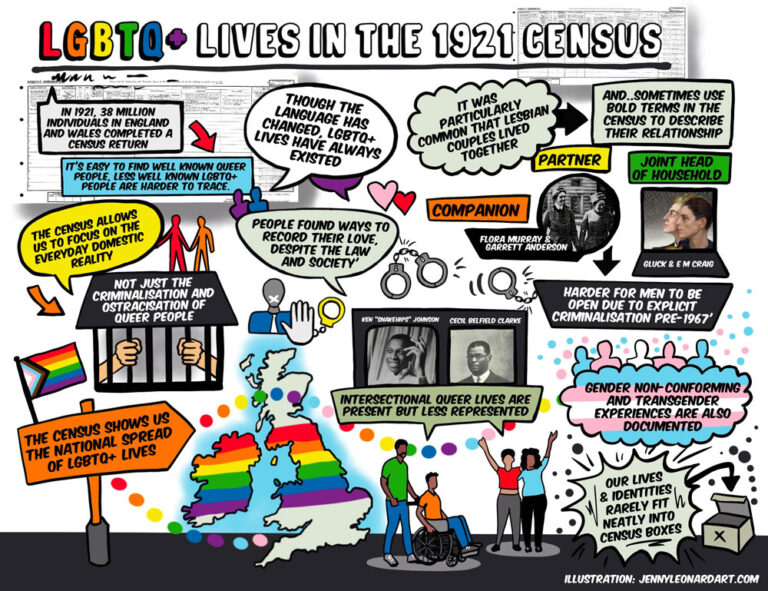

Illustrating queer census research

At the archives we have been working on finding LGBTQ+ lives through the recently released 1921 Census. To help us pull it all together, we have worked with artist Jenny Leonard. Jenny has illustrated the key research themes from this work, highlighting some of the research barriers around locating intersectional queer lives and potential research techniques. The artwork also shows some of the research successes uncovered. Enjoy!

Intersectional identities

Queer lives on the census are a minority, even more so when combined with other factors. Intersectionality acknowledges the cumulative identities people have (ethnicity, sex, class, sexuality, gender) and the complex way in which these interact to impact on discrimination and privilege.

Racialised queer lives in 1921

There is a notable under-representation of queer Black, Asian and Ethnic Minority (see footnote 1) lives on the 1921 Census. Ethnicity was not recorded on the census at this point. The census data also shows more than 1.2 million (3.4%) citizens in the 1920s were born outside of England and Wales. Many other Black, Asian and Ethnic minority individuals would have been born in England and Wales, but this level of ethnic detail is not specified (just as sexuality wasn’t).

My colleague Jessamy’s blog on researching Black history in the 1921 Census highlights some of the complexities in researching individuals of Black heritage in census records. My colleague Kevin shows the potential of some of the people that can be found, from Harold Moody to Fanny Eaton (see footnote 2).

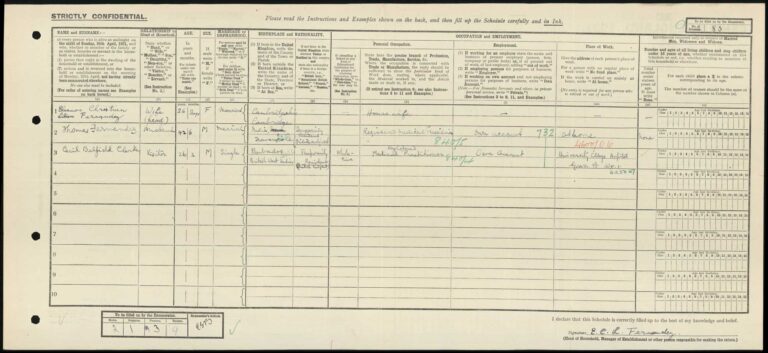

Despite this, racialised queer lives can be found on the census (see footnote 3). Cecil Belfield Clarke was a Barbadian-born physician and pan-Africanist. In the 1921 Census, he is noted as living at 79 Sutton Court Road, Chiswick and listed as a ‘Retired medical practitioner’. Clarke was one of the founders of the League of Coloured Peoples, a pioneering UK based civil-rights organisation, which was founded ten years after this census, in 1931. Among the organisation’s aims were to promote and protect the social, educational, economic and political interests of its members, and to interest members in the welfare of ‘Coloured Peoples’ in all parts of the world (see footnote 4). Clarke’s life partner was Pat Walker, although it seems they did not live together until after 1921. They are recorded as living together on the 1939 Register.

Ivor Gustavus Cummings, known as the ‘gay father of the Windrush generation’, is on the 1921 Census but is only aged 7 at the time. He was a British civil servant of Sierra Leonean ancestry, and in 1941 is believed to have become the first Black official in the British Colonial Office. In the 1930s he socialised on London’s gay scene. Rare examples of Black or Asian queer women prove harder to locate. For example, it seems suffragette Catherine Duleep Singh was out of the country with her lover, governess Lina Schäfer, in June 1921. They lived together in Germany for many years.

It appears this striking absence of Black LGBTQ+ lives is partly due to the demographic makeup of England and Wales at the time, which was increasingly multicultural, but not to the extent that it is now. However, more significantly, these individuals would have been navigating multiple intersectional identities. It was already a substantial risk to live in same-sex relationships, let alone if you were already racially marginalised, facing extra social and political barriers. Living openly in partnerships could have involved greater personal and legal risks. By the 1939 Register, though, there seems to have been a shift. More Black, Asian and Ethnic Minority couples were recorded, suggesting a marked ability to be more open just a few decades later.

We would still love to find more Black LGBTQ+ lives in the 1921 Census – let us know if you any research suggestions. We are particularly looking to identify queer Black women and LGBTQ+ people of Asian heritage.

Gender variation on the 1921 Census

A vast spectrum of sexuality and gender identity has always existed. While the 1921 Census records are from a time before current understandings of gender and present terminology existed, it is possible to recognise people who subverted gender norms, or actively lived their lives as a different gender to the one they were assigned at birth.

At the time, concepts of sexuality and gender identity were sometimes blurred and often not articulated in ways we now recognise. It is impossible to say how many of the people who subverted sexual and gender stereotypes would have identified in their own words, and if they had access to our modern-day language and concepts of gender.

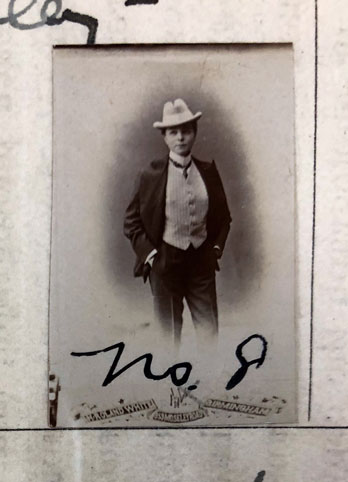

In the 1920s, there was a sense of playful subverting of gender roles. So-called ‘male impersonators’ or drag kings, such as Vesta Tilly and Hetty King, were incredibly popular on the stage, as was pageant master Gwen Lally. In certain social circles, such as the Bloomsbury group or Lamorna artists, the unconventional wearing of masculine or feminine dress was explored. Individuals such as the artist Gluck rejected gendered pronouns and traditional name formats. Similarly, Christopher St John and Tony Atwood rejected their gendered birth names. You can read more about them here.

Individuals who were assigned at birth as a different gender to the one they lived as, and had a more fixed gender presentation, are harder to locate on the census. Trans lives as we now understand them had little mainstream visibility or language to articulate this identity. Visibility would increase through the 20th century.

Many of the pioneers of early medical transition were particularly young in 1921 and often living with family still, such as Mark Weston and Michael Dillon. People like Mark and Michael tend to be listed under birth names (otherwise known as dead names). The trans individuals that can be found on the census tend to be individuals that were well known, due to legal or medical battles, or by being outed in the press.

While tracing the lives and experiences of trans and gender-non-conforming individuals can prove challenging, there have always been people who lived and experienced gender variation, and the 1921 Census shows this.

While researching intersectional lives can present additional challenges, it is also vitally important to capture the full spectrum of past lived experiences. Hopefully this blog has shown how this can be done and some of the rich lives such research can help uncover.