How did the British government communicate messages about racism and civil rights in the second half of the 20th century? One approach it adopted was the use of film, through the Central Office of Information (COI), and in surprisingly creative and thought-provoking ways.

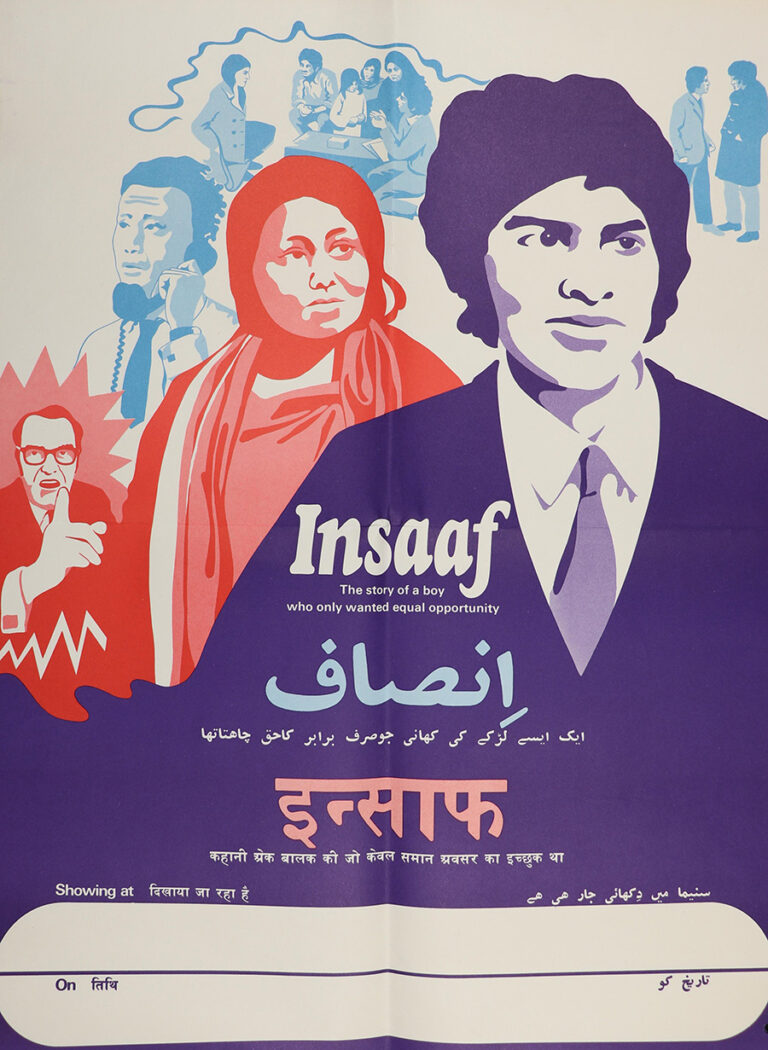

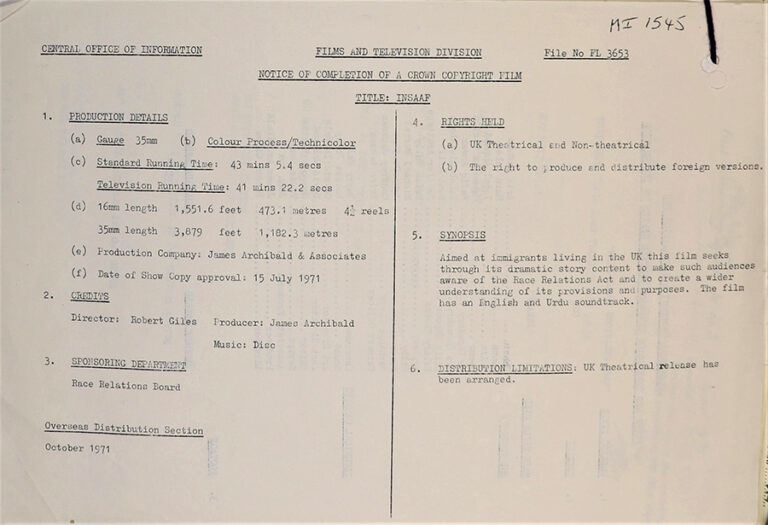

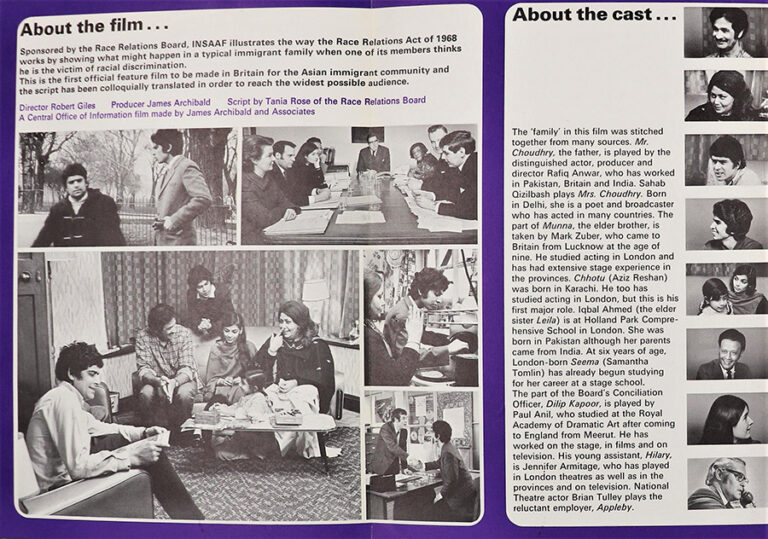

In 1971, a film titled ‘Insaaf’ (which means ‘Justice’ or ‘Fair Play’ in English) was produced. The film was partly in Urdu and targeted a specific audience of members of the British South Asian community with the aim of informing them of their rights under the 1968 Race Relations Act. The film is available to watch online on BFI Player.

It is unusual in its approach to the subject in that it presents a coherent storyline, focusing on one young man and his family and the difficulties they encounter. This approach makes it a fascinating film to watch today as it opens up a window on a particular cultural group (or a government portrayal of that group) and raises interesting questions about culture, language, representation and the history of South Asian communities in Britain.

It is currently South Asian Heritage Month, so to mark the occasion, I’m going to explore ‘Insaaf’ in more depth, drawing on personal insights from myself and our Regional Community Partnerships Manager, Iqbal Singh. This blog is based on a video discussion held by The National Archives, which you can watch in full here.

We’re also currently celebrating 75 years since the establishment of the Central Office of Information, the organisation responsible for most of Britain’s public information films. To find out more about what we’re doing to mark the anniversary, click here.

Chhotu’s story

At the beginning of ‘Insaaf’, we’re introduced to a teenage boy Chhotu Choudhry (‘Chhotu’ is an affectionate nickname given by his family). He has just left school and, on the advice of his careers advisor, is off to an interview for the position of Trainee Wages Clerk at a local company. His interview is a success, and as his interviewers leave the room, Chhotu overhears them say ‘he’s just the sort of bloke we want … if we can get him past the old man.’

We learn in a later scene that ‘the old man’, the company director Mr Appleby, is completely set against employing Chhotu solely on the grounds of his race. He argues with his colleagues over the point, openly making racist remarks and saying ‘they’re not like us’.

After receiving a letter of rejection for the job, Chhotu sits down to dinner with his family and they have an interesting and nuanced discussion in Urdu about work, education and racism in Britain. His brother, Munna, believes Chhotu has been living ‘a life of make-believe’ thinking that all he needs to succeed in life are GCEs, when actually ‘a man also needs a white skin in this country if he is to get anywhere.’ Their parents maintain that Chhotu should focus on studying and doesn’t need to work just yet[ref]COI production file: ‘Insaaf, or Fair Play’, Script, pp. 13-14, INF 6/1584.[/ref].

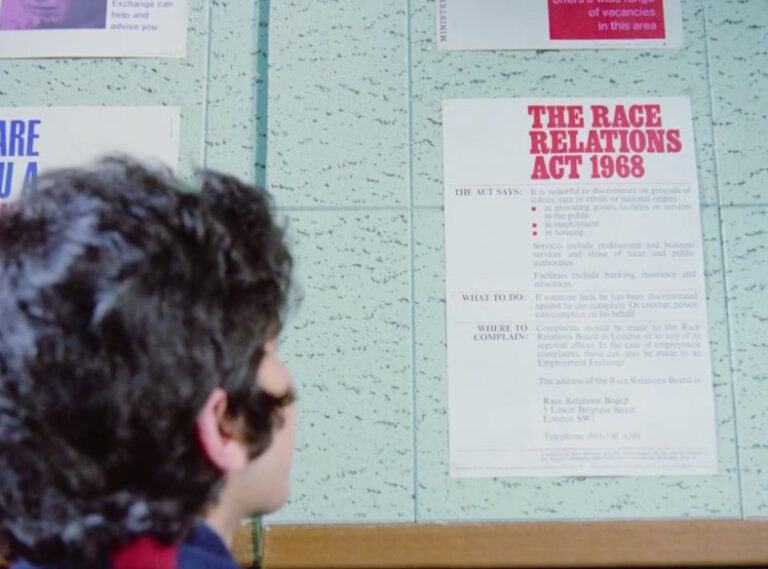

Chhotu visits the Employment Exchange and sees a poster giving the facts about the 1968 Race Relations Act. He completes and sends off a form to make a complaint to the Race Relations Board about the unfair treatment he received. The Race Relations Board had been established in 1966, as a result of the 1965 Race Relations Act, to enquire into reports of racial discrimination[ref]The Cabinet Papers, Discrimination and race relations policy, The National Archives.[/ref].

In the second half of the film, we are shown how the complaint is assessed by the Race Relations Board. Two representatives, Dilip Kapoor and Hilary Thomas, visit the Choudhry family home to discuss the complaint and reassure them. A report is drafted and discussed at a committee. Eventually, it is decided that Mr Appleby did act unlawfully by refusing Chhotu the job, and on a phone call with Dilip, Mr Appleby makes a settlement. Chhotu received two weeks’ wages (what he would have earned if he had been employed in the first place) and an offer of a job with the company.

Representing South Asian communities

‘Insaaf’ is designed to speak to an audience of South Asians living in Britain. To achieve this, the filmmakers attempt to portray on screen an average South Asian family in Britain. This is, of course, an impossible task, and it is clear that decisions were made to target a specific subset of these communities.

Urdu was chosen as the main language, although there were also versions produced with subtitles in Hindi and Bengali. While the choice of Urdu in itself narrowed the target audience, its inclusion in the film makes it far more impactful to those who understand it, even today.

Iqbal Singh, our Regional Community Partnerships Manager at The National Archives, had some fascinating insights to share about ‘Insaaf’. I spoke to him about his initial reaction to watching the film:

Immediately the Urdu in the film struck me, because that’s the language that I grew up speaking in my own family home. That made me very interested in what was being said. Having that sort of access to the language immediately made me think ‘Oh, I don’t know how many people will understand this, or how many people even at the time would have understood this’, because some of the language is quite technical and uses quite rich words. Urdu can be quite a poetic language, quite a literary language. I was very taken by it.

And partly because of my own experience with my father and his experience of working here in the 60s and 70s, the film brought up a lot of memories and thoughts about conversations that my father and I have had about employment and settling here in those formative years.

While ‘Insaaf’ includes cultural and linguistic elements that many might identify with, the film cannot successfully represent a universal family or culture, and so it is clear that there are some aspects of the film that would not be recognised by all members of the British South Asian community; many would be excluded.

Iqbal Singh comments on the class aspects of the film in particular:

It feels like there is a particular class being portrayed here, one that is conversant in both English and Urdu. So with the father character – you see him with his newspaper, you see that English is a language that they can speak. And the Urdu – it’s quite a sophisticated Urdu at times that they’re speaking. So it really feels as though there’s a particular class that’s being represented.

A lot of this is conjecture, but it’s quite interesting that when British rule was ending in India, the class of Indians that the British were negotiating with, were those Indians who were able to speak both English and Hindi, or other languages. And it’s quite interesting to see that in the late 60s and early 70s, the group that the COI is turning to with this informative film are that same class of people. And these people are not necessarily representative of most Indians in Britain at the time.

Many who came here in that period after the Second World War were working in factories. In ‘Insaaf’, we see the older brother, Munna, coming out of the factory gates, and he’s got a story, which is about his not being able to pursue his studies and having to work from a young age. I think for a lot of South Asians at that time, factory work (or work that we would not consider ‘white collar’) would have been what many were doing.

And so I think it’s really interesting that the story of this young man, who wants to get on and improve his chances in this way, maybe didn’t speak to many others who were already in Britain and who were possibly already facing quite significant racism in factories and other workplaces. This film, even with the Bengali and the Hindi versions, may still have felt quite distant. In some ways, the film feels quite quaint, like it’s in a bit of a bubble. It’s been made in a bubble.

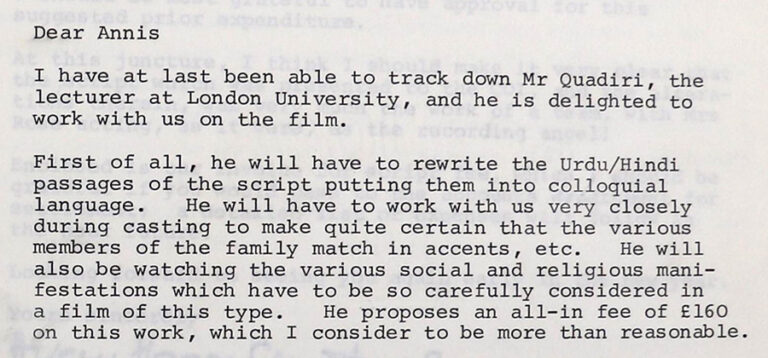

We know from the production files at The National Archives that the filmmakers did consult some individuals from the South Asian community. It seems clear however that those they spoke to were from a very specific class of educated professionals (working in academia and the media) and so this may well have influenced the way the family and the culture are depicted in the film.

The main person they consulted was a Mr Quadiri, a lecturer at London University. He was employed to ‘rewrite the Urdu/Hindi passages of the script putting them into colloquial language’, work closely with casting to ‘make quite certain that the various members of the family match in accents etc.’ and oversee ‘the various social and religious manifestations’[ref]COI production file: ‘Insaaf, or Fair Play’, Letter referencing engagement of Mr Quadiri,18 December 1970, INF 6/1584.[/ref].

Dissemination and audiences

The narrow range of people consulted and the reliance on those from a particular class no doubt contributed to the film’s overly genteel tone. ‘Insaaf’ did have a theatrical release, so it was intended to be seen in cinemas, probably targeted to specific areas of the country with South Asian communities.

Iqbal Singh considers how the film might have been received by audiences:

There was a small network that made this film. It seems like they spoke to a few people but maybe didn’t do enough research arguably. If you think about audiences at that time and the kinds of Indian films that were being shown, putting on a film like this would have felt quite odd. It’s very civil and posh in comparison. Even the young man when he speaks in the opening scene, speaks in very posh English accent.

But in some ways, I think this is a way of describing this film; it’s a posh film, trying to be like an everyday story. So how far it would have actually reached the factory-going public, or those who worked in non-white-collar work? That would have been really questionable I think.

Certainly my father’s friends were men who were working in the government, the BBC or in banks at this time, but these were very few and they were people of a particular class for whom a film like this, on one level, would appeal, because of the cultural markers that they would quickly pick up on. But I’m not sure how many in that group would really need this material. Because, certainly my father had his own employment disputes and he did get help, but I don’t think it was through any public information films like this, it was through finding things out through his own networks.

But this film was a public information film; it should have been for those who didn’t have those networks. And that’s what we do nowadays, we create films for those who maybe won’t have access to those social networks. So it is interesting that this film was made in a way that perhaps meant it could not reach those audiences.

Cultural markers

While ‘Insaaf’ may have failed to appeal to all members of South Asian communities in Britain, the filmmakers did include lots of smaller cultural markers with which many people might identify. They attempt to reflect the culture of the family through the music playing, through the inclusion of a scene where the family attend a dance performance and through the food being cooked and eaten. Iqbal Singh considers how some of these elements could be seen as part of a shared culture:

I think it’s interesting that, in a way, this film speaks of that sort of post-independence India and Pakistan, where there was a real shared heritage and a shared culture, particularly in north India, which was split apart through partition.

At the end of the film, there’s a reference to this Vilayat Khan album. Vilayat Khan is one of the greatest sitar players. He’s cherished by all the communities who love this kind of music, and it’s that music that’s being listened to at the end of the film. That itself is very interesting. I think the father has a passing line where he says ‘as long as my wife is well, and I can have some nice music, that’s all I want in my life’.

I did love the film. The scene of the mother making the chapati – it’s such a popular dish – and those kinds of markers were lovely to see. And the family interactions were really enjoyable on one level, because it was about the family showing that they’re together, that they want to help one another.

The Choudhry Family

The family interactions are really interesting to see, and they do give a lot of additional depth to the film. Many shorter public information films from the Central Office of Information can come across as quite simplistic about the issues they are presenting.

For example, there were a few other short films produced to inform people about the 1968 Race Relations Act: one from 1969 called ‘Race Relations Board’ and another from 1976 called ‘The Referee’. They communicate instructions and information from government in a simple and direct way – and this can be very effective. However what makes ‘Insaaf’ so different are the additional layers of complexity included in the discussions of the family.

Even though the main plot is resolved in a simple way, the brothers, Chhotu and Munna, debate the issue of discrimination and work. They disagree and there is conflict between the older brother and his family. This does make the story seem more real and communicates to the audience that the issues the family are encountering are not simple and opinions vary on how to address them. This adds an interesting level of subtlety which is fairly unusual in these kinds of films. Iqbal Singh:

There is this motif of the two brothers pursuing different paths in life: one doing well at school and the other not. This is a really popular storyline found in many Indian films (and one that is shared between different communities). It’s interesting that this motif was deliberately included, and you do wonder how much that motif influenced the development of the plot.

There is also an interesting dynamic between the father and his sons. I’ve received comments on this film that suggest that perhaps the father character is quite lenient to his sons – allowing them to leave school early and not reprimanding them for arguing at the dinner table – and so not typical of his generation. But of course families and individuals vary enormously, so this is just one particular viewpoint.

Iqbal Singh considers the values and aspirations of the father character:

The father also speaks of those aspirations, which were common to immigrant communities – wanting their children to get an education and to get something more for themselves than they had. But at the same time there’s the idea of keeping your head down and making something of the opportunities you received.

So there are a number of markers within the film that speak to a more general experience that many immigrants would have had of trying to come and set themselves up and not wanting to rock the proverbial boat. But again, it doesn’t necessarily always speak to the real struggles of South Asian communities in the UK. In reality, those struggles could be manifested in more vociferous ways, through striking and protesting in other ways. But certainly this film is showing one very civil side of this.

The Race Relations Board and the production of ‘Insaaf’

The film does present quite an idealistic view of how racist discrimination in employment would have been addressed by the Race Relations Board at the time. It is probably fair to say that most people who saw this film would not have experienced such a smooth process. This is of course because the film’s main aim was to inform people about their rights and encourage them to take advantage of the complaints process, by making it look painless and effective.

The racism exhibited by the employer character, Mr Appleby, is very blatant and clear-cut. This makes the plot simpler; the Race Relations Board finds it fairly easy to determine that discrimination has taken place and then the employer quickly backs down. It’s clear that in reality, these kinds of problems would often be much more complicated and much harder to prove and resolve. Miss Thomas, one of the representatives from the Race Relations Board even says at the end of the film:

‘If only it were always like this. Sometimes we can’t be so sure, we never really get to the truth. And other times it’s not a question of colour at all … Sometimes things happen that are simply unfair, that can happen to anybody. White people too. But at least we can try to explain.’

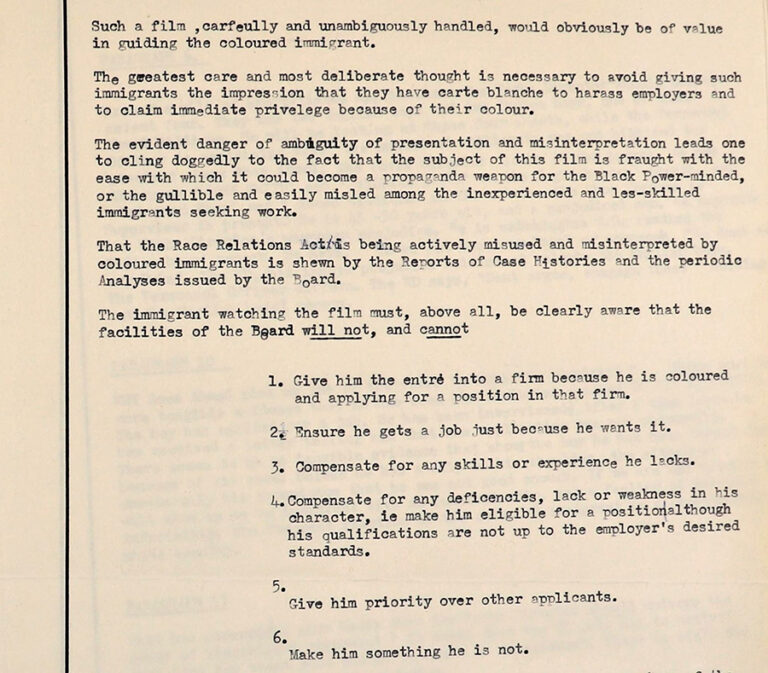

These lines come across as a little artificial and unnatural in this scene, and perhaps there was a reason for this. There is evidence in the production file for ‘Insaaf’ that at least one COI employee reviewing an early treatment of the film was concerned that the film could be misinterpreted by viewers and might encourage people to exploit the Race Relation Board’s system[ref]COI production file: ‘Insaaf, or Fair Play’, ‘Notes on Race Relations Board: Indian language film project’, INF 6/1584.[/ref]. One document states:

‘The greatest care and most deliberate thought is necessary to avoid giving such immigrants the impression that they have carte blanche to harass employers and to claim immediate privilege because of their colour.’

There is a level of cynicism and distrust of audiences exhibited in some of the production documentation for the film. There is even one suggestion that the film should include a story of an inadmissible complaint being made to the Race Relations Board, in order to discourage people from trying to exploit the complaint system. While this idea did not make it into the final film, Miss Thomas’ lines at the end may be an attempt to make this point.

A shared culture?

Iqbal Singh considers how the film succeeds in depicting a shared culture, and how we might engage with the film today in light of South Asian Heritage Month:

There’s a Hindustani that’s being spoken here. Dilip Kapoor, the lawyer and main representative of the Race Relations Board, is not a Muslim, but the family are coded as a Muslim family. The film encapsulates a shared culture that existed prior to partition, but even post-partition many of those communities still remembered how they shared with each other. And I think there’s something in this film that encapsulates that sense of sharing, that despite the horrors of partition, here in Britain you’ve got the Hindu lawyer helping his Muslim brother to get through and navigate this process. And they’re both speaking this shared language, which I think is really special.

And I think the aim of South Asian Heritage Month is to celebrate that sense of South Asia. A kind of pre-independence dream of everyone coming together and finding a kind of post-colonial happiness. So somewhere in this film, you can see signs of that dream.

For me, this is most beautifully and emotionally represented when they play that sitar music at the end, because if anything, that music has been the thing that has brought India and Pakistan together. Those shared cultural things, those markers that allow people to think there was once a time when we were together. So I think the film is a great clarion call, for that sense that there was something shared.

Opening up discussion

In this blog, we’ve discussed some of the aspects of ‘Insaaf’ that we find most interesting and our own personal responses to the film. We hope that this will encourage more people to watch the film and think about the ideas and feelings that it provokes.

Please comment below if you have any thoughts to share about this film. We would particularly appreciate hearing from members of South Asian communities and if anyone actually remembers seeing this film when it was shown in the 1970s!