In Their Own Write is an ambitious research project which is uncovering the voice of the poor in 19th-century England and Wales, using MH 12, the collection of correspondence between central Poor Law authorities and local Poor Law Unions, dating from 1834 to 1900.

Buried within this massive collection of administrative material are letters (and other documents) from the poor themselves. They wrote for many different reasons: to ask for help negotiating the complex poor laws; to dispute the level of relief they received; begging not to be sent to the workhouse or asking to be sent there; or complaining bitterly about the treatment they received.

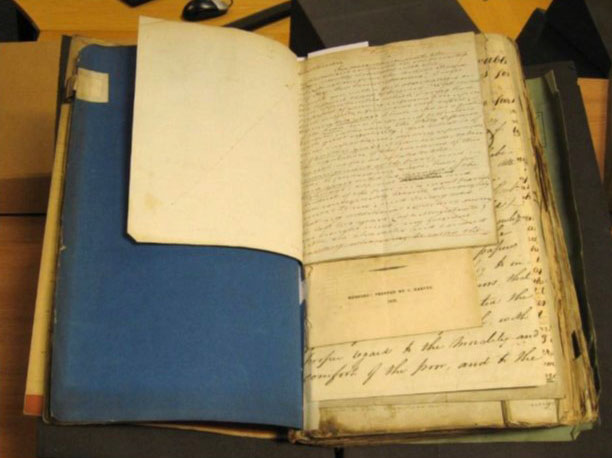

For two and half years our fantastic band of nearly 40 volunteers (some working at The National Archives and some remotely) have been painstakingly searching through MH 12 volumes, looking for these letters, photographing and then transcribing them – no mean feat as most are handwritten, and the 19th-century poor are not renowned for their elegant hand. By the time Covid-19 interrupted our well-oiled wheels, we had completed over 95% of the work.

And what we have achieved is nothing short of wonderful. To date we have found nearly 7,000 letters and transcribed 6,666 of these, or three million words!

It’s a tremendous achievement, which we could not have done without our intrepid band of volunteers. It has been doubly frustrating, then, that lockdown prevented us from completing the final bits of surveying and imaging – which could only be done in the office. As a result, there are still around 500 letters to be imaged and two Unions we didn’t quite finish surveying (Chelmsford, and Wandsworth and Clapham) – so there will be an additional number from these sources too.

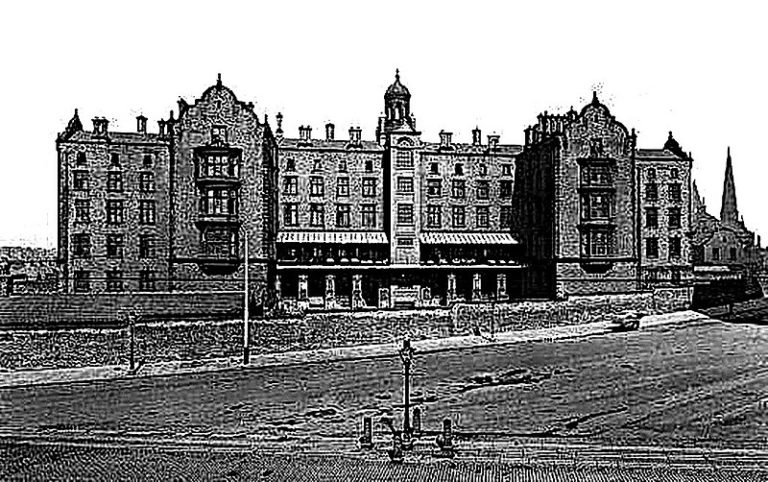

So, with 95% of the work finished we can begin to stand back and observe what we have found. It seems clear that the most vociferous (and quarrelsome?) poor were located in the large cities of the north of England and in London: Bethnal Green (with the highest cache of 459), Wandsworth and Clapham, Liverpool, Sheffield, Bradford, Chelsea, Barnsley and York all featured in the top 10. And Birmingham, not surprisingly, was also high in the table with 450 items.

The happiest, or most oppressed, poor (depending on your interpretation) represent very different communities, based in remote, rural locations such as Wem in Shropshire and Wheatenhurst in Gloucestershire. The poor of Alston with Garrigill in deepest Northumberland appeared to be either almost comatose or deliriously happy with their lot; in the whole period of the study the Poor Law Commissioners in London received only two letters from this Union, both from Thomas Robson.

Robson was a 79-year-old retired miner, trying to claim relief to support him in his extreme old age. He provides a detailed picture of his attempts to persuade the Guardians to pay him what he believed he was owed. Like many trying to claim relief, Robson was caught between two Unions – one where he had worked almost his entire life and the other where he was born. The two Unions passed his claim back and forth, while Robson tried to tie them down. And let’s not forget, somehow he was travelling from one place to another to present his case in person, in a time when public transport was almost non-existent and certainly too expensive for a poor man trying to claim poor relief. His letter to the Poor Law Board begging help in resolving the matter was an act of desperation on his part.

Our volunteers have been sharing other stories they have come across. Some of the letters are long and rambling – verging on incoherent: the incoherence caused in part by frustration but also probably by a limited level of literacy.

One such letter came from Jane Maylor, an inmate of Liverpool workhouse. She wrote a 36-page, close-handwritten diatribe against conditions in the workhouse hospital, and in particular against the matron, a nurse and a doctor. The letter ranged wildly across a mass of accusations including drunkenness amongst the nurses, interference with diet and medicines and regular dancing which kept inmates awake. In one example, she recalled how the matron had threatened to keep a patient in the hospital after she had threatened ‘go to the papers’ with her story on her release. In another, Maylor witnessed an exchange between a patient and one of the doctors. The patient had breast cancer, and while conducting his examination, the doctor asked if she was married. When the patient admitted she was not, the doctor responded ‘that is what people get from not being Maried’!

Maylor was horrified by the inhumanity of the doctor. She was also offended by the practice among staff of referring to older inmates as ‘old stagers’. ‘Where is the poor to go when they are friendless and poor but to a Workhouse Hospital’, she asked, claiming it was such cold-heartedness on the part of officials which made her leave.

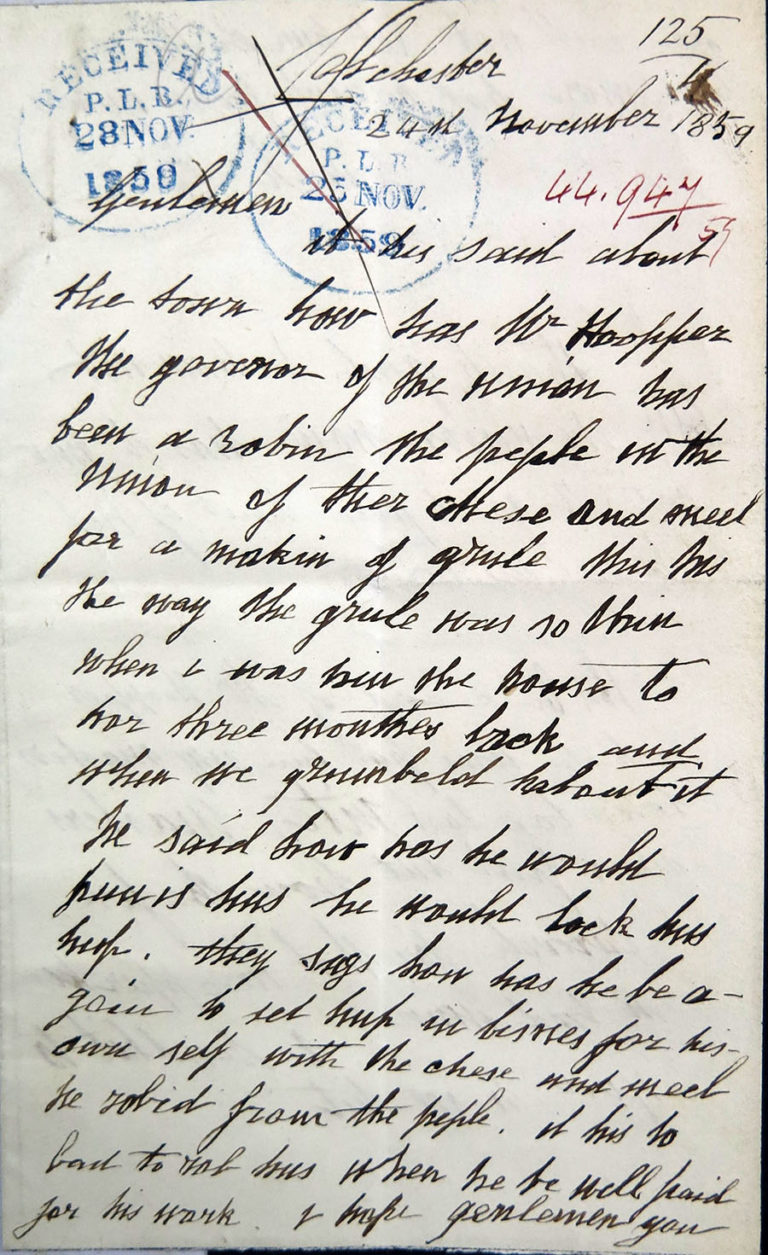

The volunteer who had to transcribe Maylor’s letter was driven to distraction by its incoherence but the story she tells is vivid, the more so because it is in her own words. One of the interesting things about the letters is their ability to bring the pauper voice to life. Some enable us to ‘hear’ their accents and their dialects, especially if read aloud. Often written phonetically, using local vernacular they offer a rare insight into the language of the poor. This letter from Sarah of Colchester is a good example:

Gentlemen

it his said about the town how has Mr Hoopper the govenor of the union has been a robin the peple in the union of ther chese and meet for a makin of grule this his the way the grule was so thin when i was hin the house to hor three monthes back and when we grumbeld habout it he said how has he would punis hus he would lock hus hup. they says how has he be again to set hup in bisnes for his own self with the chese and meet he robid from the peple. it his to bad to rob hus when he be well paid for his work. I hope genlemen you will not let him do this so no mor hat present from yours

Sarah H

P.S. Thank god I ham not hin the union now has I hav got a good plac hout of hit becus [ive] written

In Their Own Write will provide a unique insight into the thoughts, concerns and battles of the poor in Victorian England and Wales. At the end of the project all the transcriptions will be loaded into a free-to-access database, through which the public and researchers will be able to delve into the rich material it has found.

In Their Own Write is a three-year collaborative project with a team of historians at Leicester University led by Professor Steven King and by Paul Carter at The National Archives. It is funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council. You can read the regular blogs written by the team at https://intheirownwriteblog.com/.

Wow – I’m so amazed by this collection and very much looking forward to seeing the results of all your volunteers’ hard work – I have ancestors in Bethnal Green so hope to find something. Even if I don’t, I might still discover something new from reading the words of others. Thanks so much for all you do!

The voice of the common folk … A wonderful project and, having worked with a range of similar documents myself, a marvel of de-encryption.

My congratulations to these dedicated volunteers. May their labours bring forth new researchers and supporters for this national treasure.

Can you research individuals from the material that has been transcribed? I’m researching relatives who required assistance from one or other of the Glasgow poorhouses/workhouses. I have a record of one seeking poor relief and three who died n the poorhouse, but have not been able to trace where they lived or worked, partly because of the fact that there are literally thousands of Scots with the same name, Alexander Macmillan, who lived in mid-late 19th century Glasgow. the many variations of the spelling of the surname is also a problem. I live in Australia so am unable to attend the libraries in person, at least for the foreseeable future.

Thanks

Agnes Macmillan

Hi Agnes

I’m afraid In Their Own Write only covers institutions which made up the English and Welsh system of Poor Relief. There was a separate system in operation in Scotland, so to research Scottish ancestors you would need to contact the National Records for Scotland. This link leads to a research guide for poor relief in Scotland: https://www.nrscotland.gov.uk/research/guides/poor-relief-records; or Glasgow Archives at the Mitchell Library https://www.glasgowlife.org.uk/libraries/city-archives/collections#county-councils-8, for Glasgow records specifically.

Sue Hawkins, In Their Own Write

An interesting study was carried out by volunteers. I can imagine how difficult it is to read these sentimental notes and letters of poor people. The letter from Jane Maylor about the inhuman attitude towards prisoners and the callousness of officials was especially struck. I will use this information for my historical written research.

I listened to this recording and was amazed to hear about the man who’s wife had dementia. The man had asked to be awarded a small allowance so that he could look after her, because she was too senile to be left on her own. I was astonished to find that they replied, saying they could only offer him work.