Please note that this blog post references language as it was used at the time. Some of this language is now outdated and/or potentially considered offensive.

The majority of records relating to sex work in the archives are about female sex workers; however, there have also always been men who have sold sex, predominantly to other men[ref]Interestingly there is substantially less evidence of male sex workers working with female clients; it remains a hidden history, and seemingly a more recent phenomenon.[/ref].

Men engaged historically in sex work faced a double stigma as both homosexuality and sex work were controversial in their own right[ref]Weeks, Jeffrey. Against Nature: Essays on History, Sexuality and Identity (London: Rivers Oram Press, 1991), p.47.[/ref]. Sex work between men also involved a significant extra layer of risk, as before 1967 in England and Wales homosexual acts between men were illegal (whereas women engaging in sex work was not in itself illegal, although many associated practices were criminalised). The increased risk meant this work was often less visible and men were less likely to openly solicit. Even after 1967, the Sexual Offences Act had a clause about ‘Living on earnings of male prostitution’[ref]Sexual Offences Act 1967, c 60, An Act to amend the law of England and Wales relating to homosexual acts.[/ref].

As with so many things historically, it seems the societal assumptions about sex work were ‘staggeringly heteronormative’[ref]Lister, Kate. A Curious History of Sex. (London: Unbound, 2020), p.332.[/ref]. Male sex workers presented a challenge to the many stereotypes that surrounded female sex workers, such as a lack of agency and choice. Despite this, reports of male sex work and male brothels had been longstanding and, at times, prominent in the public eye. This can be seen in the case against Oscar Wilde, in which he was linked to a series of young male sex workers. In the treason case against Roger Casement in 1916 controversial diaries were used to discredit him, citing his sexuality and regular visits to male sex workers[ref]While the authorship of the diaries, known as the Black Diaries, has long been disputed, they are now generally accepted as genuine. Paul Hyde, Lost to History: An Assessment and Review of the Casement Black Diaries, Breac: A Digital Journal of Irish Studies, 2016.[/ref]. These cases indicate the controversy of male sex work for client and worker, and the ability to discredit someone or leave them vulnerable to blackmail.

Language and the law

The language in these records can be complex and nuanced; queer-friendly clubs were raided as ‘disorderly houses’, a charge that often related to brothels. Whereas men importuning or soliciting for sex in the records can often just mean men looking for sex, rather than men looking for people to pay for or sell sex. The criminalisation of homosexual acts between men mean it is often hard to differentiate in the records between sex where money is exchanged, and sex where it was not, because all of it was subject to the law in some way.

As with other sex workers in our collections, much of the evidence is statistical and impersonal in nature, but with surprisingly revealing stories littered throughout.

‘Professional Mary Annes’

In 1889, the Cleveland Street scandal took place, when a male brothel run by Charles Hammond on Cleveland Street, London, was discovered by police. There are many resulting Director of Public Prosecutions files including trial transcripts, newspaper clippings and statements in The National Archives’ collections. The case proved a very public scandal and received significant press attention.

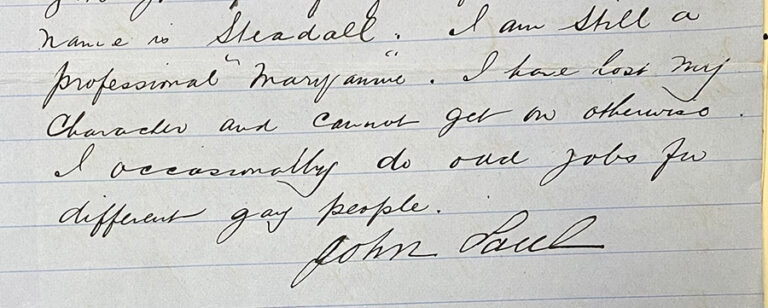

Our records include the original statement and correspondence of John Saul. Saul was a known Irish sex worker who worked in London and gave a controversially frank testimony as part of the case. In his testimony, Saul of 15 Old Compton Street, said of himself and brothel keeper Hammond: ‘we both earned our livelihood as sodomites.’ Saul used the terms ‘professional sodomite’ and ‘Mary Anne’ to refer to his work in his statement. The term ‘Mary Anne’ was a coded expression from the time for a male sex worker.

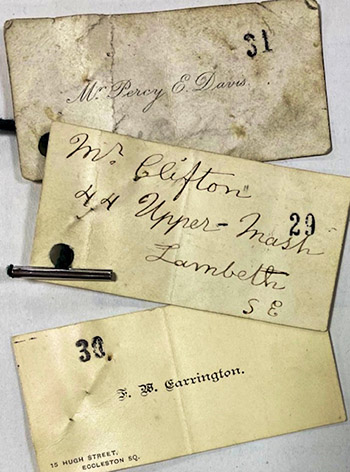

With his testimony, Saul provided visiting cards of three other sex workers. Concluding his evidence Saul wrote: ‘I am still a professional “Mary Anne”. I have lost my character and cannot get on otherwise. I occasionally do odd jobs for different gay people.’ [ref]The word ‘gay’ at this time could have referred to sex work (a gay house, referred to a brothel at this time) or homosexual men.[/ref] While this testimony is framed within the criminal justice system, it is also powerfully written in Saul’s own words and the language he identified with and used at the time. Despite Saul’s open confession, he was not prosecuted.

‘Boy harlots’

A few decades later, in 1925, three men were noted by police as smiling at gentlemen as they passed, swaying their bodies in a ‘girlish manner’ and blowing kisses at men they approached[ref]Importuning male persons, 1925. MEPO 3/403, The National Archives.[/ref]. Records report them laughing heartily, walking arm in arm into Great Windmill Street; these men were soliciting for sex. This was in the heart of Soho, already a centre for selling sex at this time. Much of this file focuses on the charge that should be given for an ‘importuning male person’. Such procedural cases can prove to be surprisingly rich and detailed.

The men boldly approached and spoke to various gentlemen, with lines such as ‘Are you looking for a nice boy?’ and ‘Hello darling. Do you feel naughty?’ In the latter instance the man replied: ‘What! Boy harlots now!’ The element of surprise in this remark potentially hints at how uncommon it would have been to see men so explicitly soliciting at this time. The friends then turned on to Shaftsbury Avenue and approached another man: ‘Come along darling. Let us all go to your flat. We will make a fuss of you.’ One of the soliciting men said: ‘Won’t it be ripping. I hope you have got a nice warm bed.’ Unfortunately, for these smiling and giggling men, it turned out that this time they had unwittingly approached police officers.

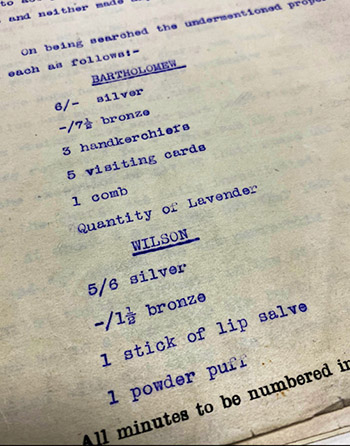

The men were arrested and the charges discussed. The items on the men at the time were seized as evidence, including handkerchiefs, a number of visiting cards, a comb, lip salves, more than one powderpuff and a quantity of lavender. One of the defendant’s mothers claimed the powder puff and tube of lip salve, found in his possession, were her property and were with him by chance. Although on being questioned, the seized items do not match her description[ref]A similar case is noted in Matt Houlbrook’s, ‘The Man with the Powderpuff in Interwar London’, 2007.[/ref]. Gender identity is complex in these records, with many traditionally feminine traits being seen as visual signifiers of homosexuality and, in this instance, sex work. This is heavily noted upon in the records, alluded to through gestures and walking styles, comments and flirtations, and material culture, such as the powder puffs, lipsticks and rouge.

The sex workers involved appear to want to avoid bail through fear of people at their addresses finding out about their arrests. This indicates the shame and stigma attached to being a male sex worker, and potentially wanting to protect other people they lived with. One individual says: ‘No thanks. I don’t want my people to know.’

Throughout history male sex work has come with significant stigma and risks. This is reflected in the rich archive material that survives. This blog has highlighted just a few cases – there is much more to explore in these complex and nuanced records.

The comment about living off the immoral earnings of male prostitutes is no different to that applied to living off the immoral earnings of women. The ‘Cleveland Street Scandal’ it is said that ‘Prince Eddie’, a direct heir to the Throne, and would have been King before George V, Eddie was said to be bisexual was there at the time and the sentences handed out to the boy messengers were much more tough, including being sent overseas. As far as Saul goes he apparently had a colourful life, being asked in one case to give evidence to a trial in Dublin but he was never called.

In the post war period, very few of the importuning charges were against sex workers. The majority of male importuning offences were men seeking sex with men in public lavatories (known as ‘cottaging’) (with no payment involved). Brain Lewis’s book ‘Wolfenden Witnesses’ (2016) is recommended reading on this subject.

I had the great privilege of being one of the guides for the National Trust’s reconstruction of the short lived ‘Caravan Club’ taking groups on tours of Soho’s queer history. As part of this programme, we had a familiarisation trip to the archives at Kew (which I still think of as the more prosaic Public Records Office).

It was a profound experience as we were allowed to peruse the actual police reports and prosecution submissions for cases of cottaging and other acts of public indecency. In particular, there was a case of two men prosecuted for an act of ‘mutual consolation’ (my words) in a public convenience in Brixton.

I felt such a pang of sadness at the industry with which the authorities of the day, urged on by society in general, I suppose, sought to persecute these two gents and make public examples of them, their misdeeds chronicled in absurd degrees of detail before the courts.

There was more than a degree of fetishisation on the part of the boys in blue, also, with police statements often rendered with a slurp of relish.

Thank heavens for the National Archives though. I do fear that future generations will not treasure this resource for what it is. Particularly, as we move beyond paper records.

Consider the permanency of a retained paper record, or a professionally printed picture, safely stored, as against its digital counterpart which will have to survive migration across ever changing digital platforms.