The life and published works of British author Radclyffe Hall (1880-1943) were hugely influential in providing visibility for LGBTQ+ individuals. Her lesbian novel, ‘The Well of Loneliness’, was published in 1928 by publisher Jonathan Cape, and while it solidified her status as a queer icon, the text itself was met with much resistance due to its portrayals of female same-sex relationships and gender non-conformity.

But despite attempts to suppress the text and its subsequent banning, the publicity that the novel received, along with surviving documents from the text’s obscenity trial (held at The National Archives) and correspondence held at the Cadbury Research Library: Special Collections at the University of Birmingham, continue to provide greater visibility of LGBTQ+ individuals throughout history.

This blog post will shed light on Hall’s impact on queer history, the obstacles she faced, and the importance of highlighting diversity within the archives to provide greater visibility of LGBTQ+ lives.

Due to the mixed response to Hall’s novel and the nature of the obscenity trial that occurred, the information included in this blog post may include terminology that we no longer use. Similarly, as we are unable to understand exactly how individuals from the past would have liked to have identified, I will sometimes be using both ‘queer’ and ‘LGBTQ+’ as an umbrella term.

‘A prosecution would undoubtedly give the book further advertisement’

Catalogue ref: CUST 49/1057

Same-sex relationships between women have never been illegal in Britain. Rumour has it that lesbianism was not criminalised following Queen Victoria’s refusal to believe that lesbians even existed[ref]According to legend, the 1885 Criminal Law Amendment Act originally sought to criminalise same-sex relations between men and women, but that the Queen refused to sign off on the amendment due to her belief that ‘women do not do such things’.[/ref]. However, it was not until the 1921 Criminal Law Amendment Act that a discussion regarding ‘Act[s] of gross indecency between female persons’ and the punishment of these ‘in the same manner as any such act committed by male persons’ would occur. Despite some deliberation, same-sex relations between women were not criminalised, as many parliamentarians did not believe that women had sexual relationships with other women, while others were concerned that such an amendment to the law would provide unwanted visibility.

‘the overwhelming majority of women of this country have never heard of this thing at all … I would be bold enough to say that of every thousand women, taken as a whole, 999 have never even heard a whisper of these practices’

Lord Birkhead, the Lord Chancellor[ref]Commons Amendment, vol 43: debated on Monday 15 August 1928.[/ref]

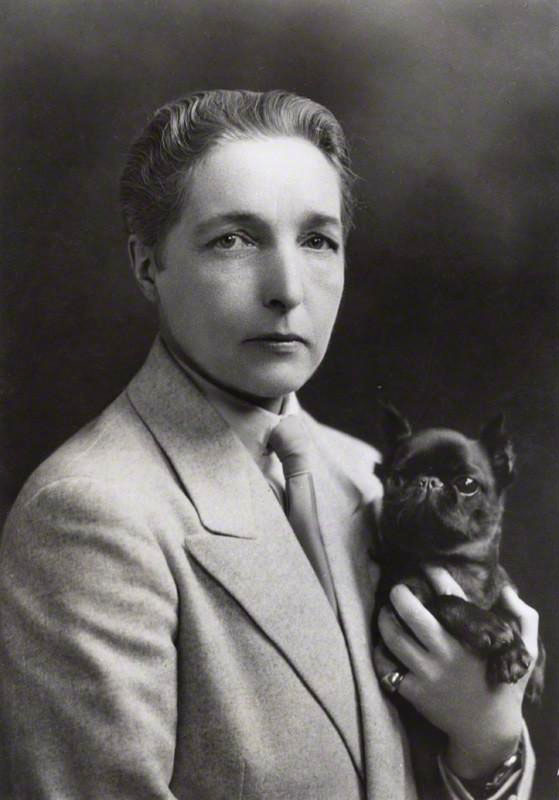

Radclyffe Hall identified as a ‘congenital invert’, a sexological term used to describe an individual that is (and always has been) attracted to people of the same sex. In 1907 she met her first long-term partner, the singer Mabel ‘Layde’ Batten, and later, in 1915, began an affair with sculptor Una Troubridge. Hall and Troubridge would begin living together in 1917 and would be in a relationship for the rest of Hall’s life.

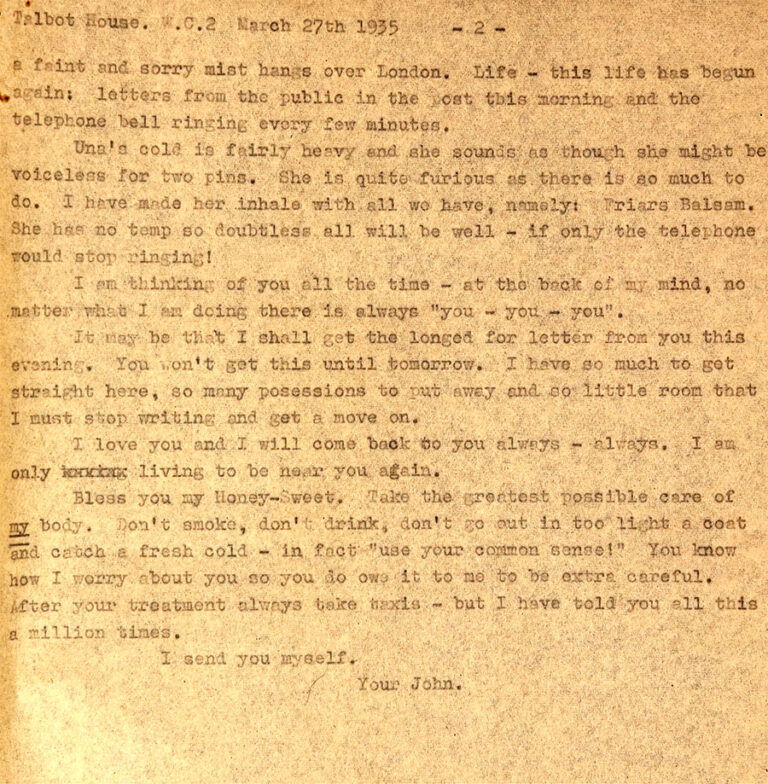

The author had a number of affairs throughout this time, including with singer Ethel Waters and Hall’s nurse, Evguenia Souline. Love letters to Souline held at the Cadbury Research Library provide further insight into Hall’s sexuality and gender identity, as do pictures of the author. Hall would sign letters from ‘John’, and for most of her life she preferred more masculine fashions and styles. Researchers have argued that these demonstrate how Hall was comfortable with her sexuality and non-normative gender presentation.

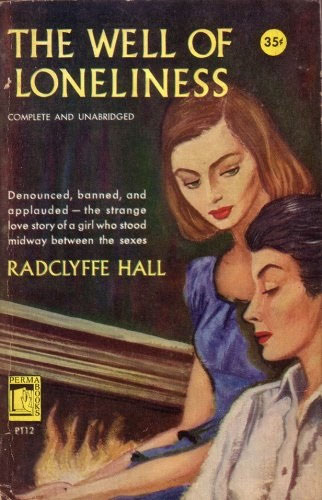

Published in 1928, Hall’s novel ‘The Well of Loneliness’ explores the struggles of ‘invert’ Stephen Gordon, an upper-class masculine woman coming to terms with her gender, her sexuality, and her place in Victorian society. It is possible that Stephen’s story may have been partially autobiographical, while simultaneously and evidently influenced by the emergence of research called sexology.

The scientific study of human sexuality, sexologists researched what they regarded as being non-normative sexual behaviour and desires. ‘Sexual inversion’ was the term used to describe same sex desires and thus homosexuals were termed ‘inverts’. Hall herself described ‘The Well of Loneliness’ as being ‘the first long and very serious novel entirely upon the subject of sexual inversion’, and British sexologist Havelock Ellis provided a commentary for the first edition of the text[ref]Laura Doan, ‘Fashioning Sapphism’ (2000, p. 31).[/ref].

‘The Well of Loneliness’ was arguably the first of its kind – a British lesbian-novel, and for that reason it has become iconic[ref]At this time, parts of Europe (Paris especially) were known for having an already large and visible queer culture.[/ref]. Only seven years after discussions in Parliament about the existence of lesbian relationships, the text sought to provide LGBTQ+ visibility on a large scale, in particular for queer women.

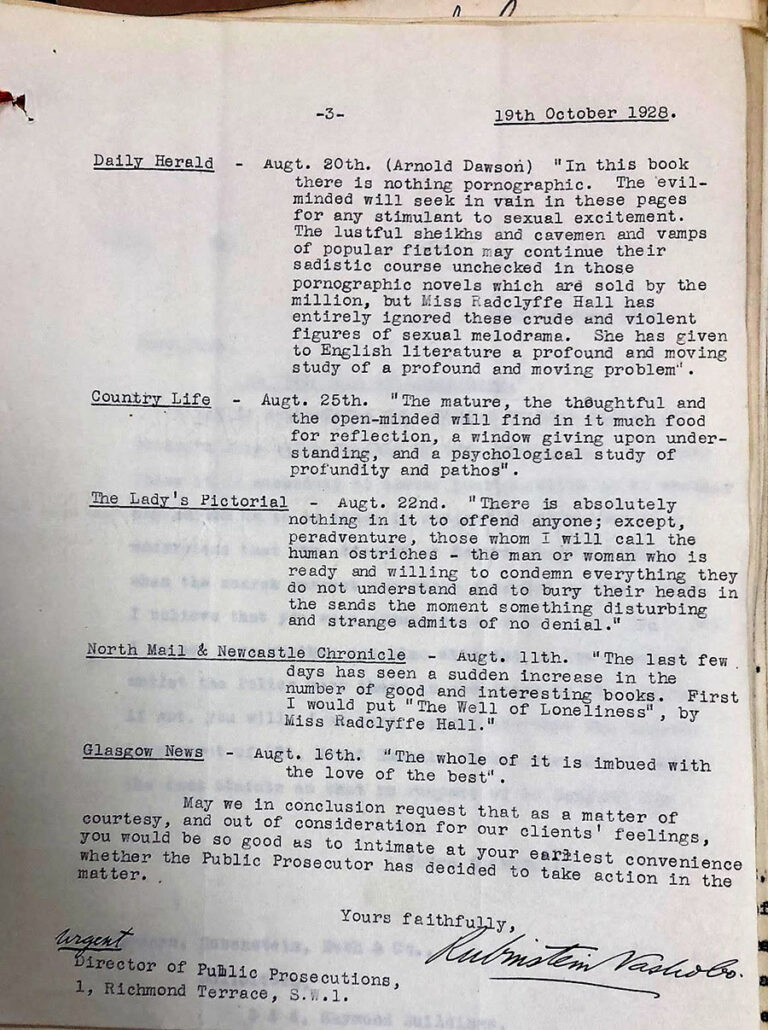

Despite its potentially controversial content, many reviews of Hall’s novel were very complimentary. Country Life magazine wrote that ‘The mature, the thoughtful and the open-minded will find in it much food for reflection, a window giving upon understanding, and a psychological study of profundity and pathos’ (DPP 1/88), and the Daily Herald noted that Hall had ‘given to English literature a profound and moving study of a profound and moving problem’ (DPP 1/88). But not everyone felt this way about ‘The Well of Loneliness’.

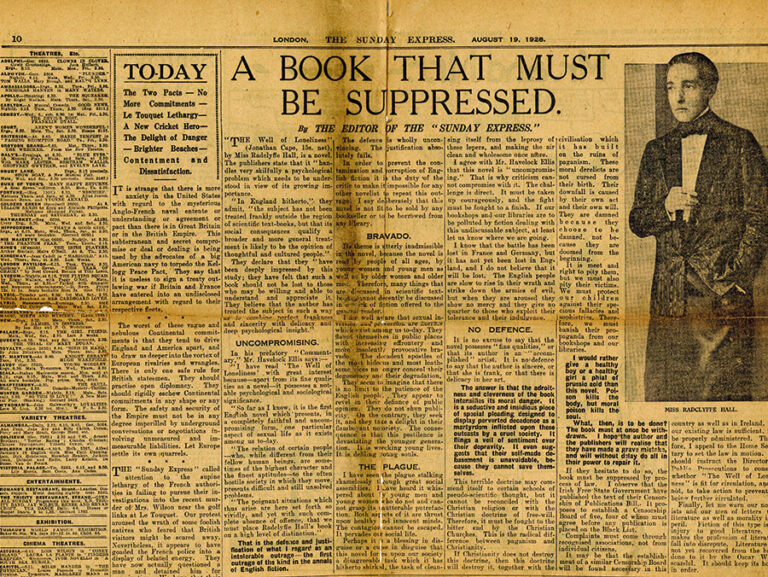

In August 1928, moralist James Douglas, editor of The Sunday Express, launched a scathing attack on Hall and her novel. In an editorial piece titled ‘A Book That Must Be Suppressed’, Douglas regarded the novel to be ‘an intolerable outrage – the first outrage of its kind in the annals of English fiction’ (DP 1/88) and argued that ‘the cleverness of the book intensifies its moral danger…The book must at once be withdrawn. I hope the author and the publishers will realise that they have made a grave mistake, and will without delay do all in their power to repair it’ (DP 1/88). Douglas subsequently called on the Home Secretary, Viscount George Cave, to act in the instance that Hall and her publishers would not.

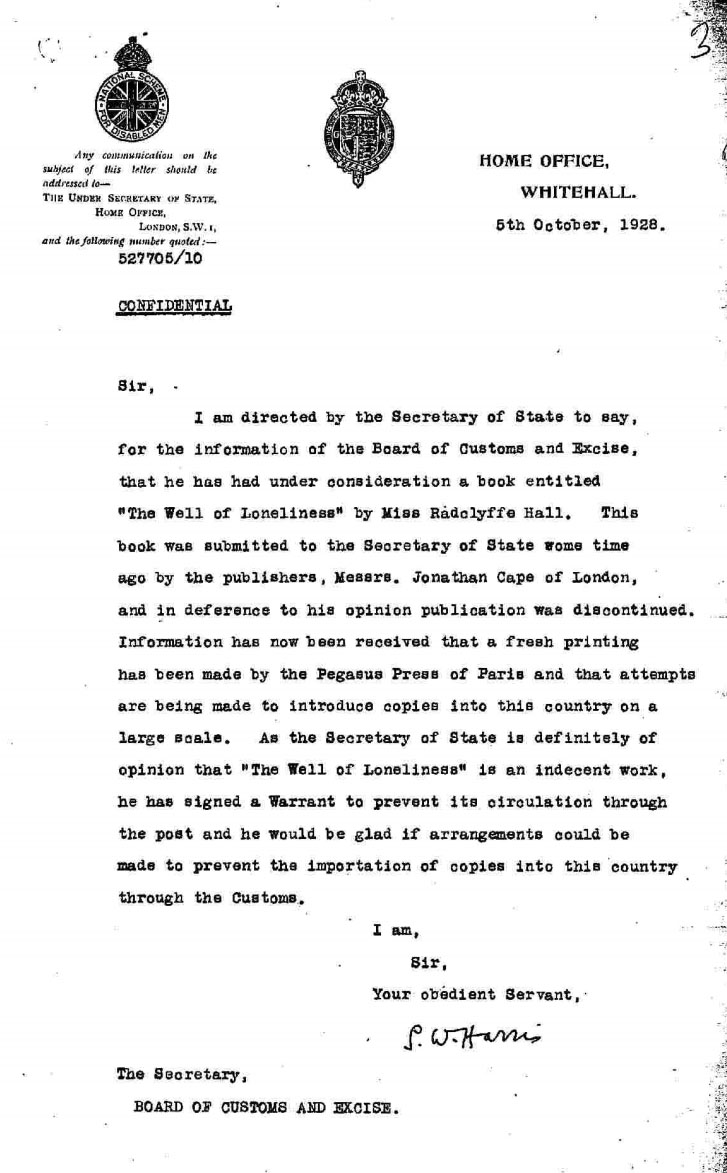

Rather than cease publishing, Jonathan Cape sent a copy of the novel to the Home Secretary in the hope that he would recognise its literary significance, and acknowledge the lack of obscenity within it. However, Viscount Cave informed Cape that he felt it would be ‘gravely detrimental to the public interest’ if they were to continue publishing and demanded that they should cease immediately, or face criminal charges[ref]Diana Souhami, ‘The Trials of Radclyffe Hall’, (1998, p. 194).[/ref]. Publishing stopped momentarily while Jonathan Cape secretly leased the rights to French publishing house Pegasus Press. The novel’s controversy in the press had attracted global attention and demand was steadily increasing. But this did not go unnoticed, and on 3 October 1928 a warrant was issued to seize shipments of the text. As a result, hundreds of copies were obtained and later destroyed.

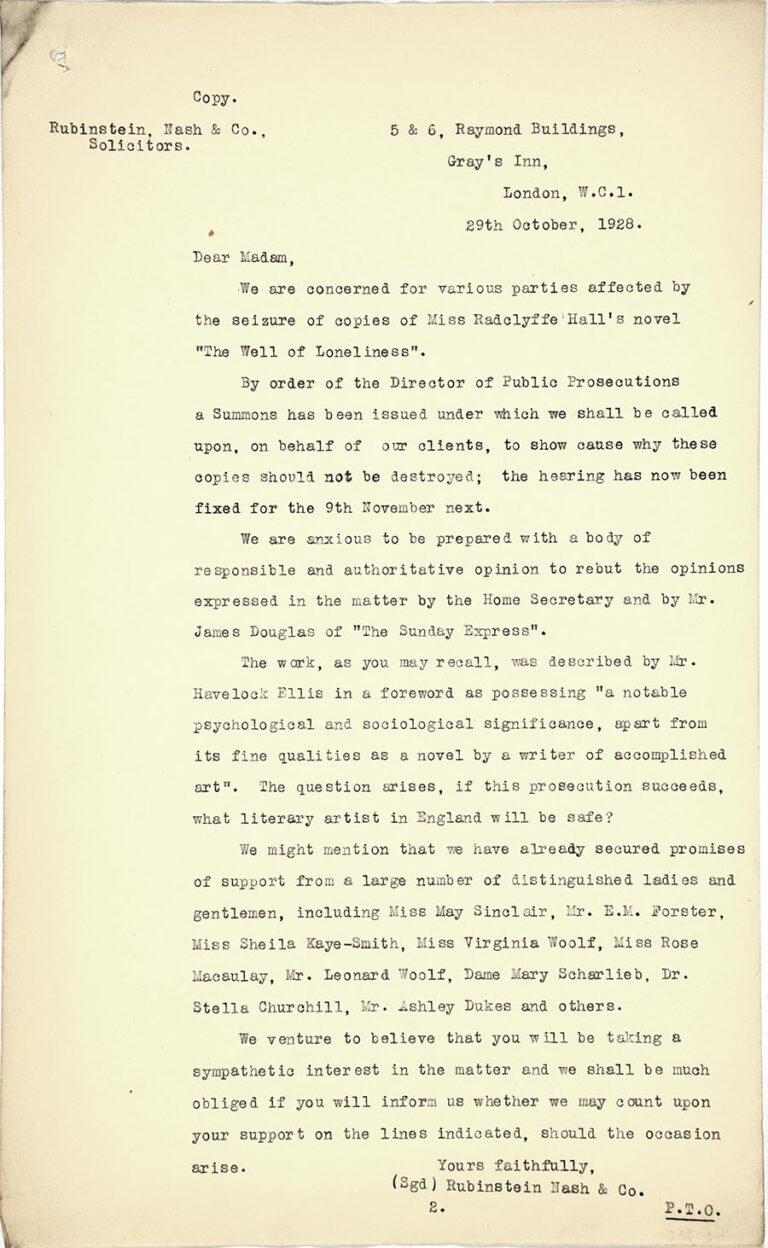

An obscenity trial was to follow on 9 November 1928. Fellow authors and creatives were outraged at the government’s actions, and publicly supported Hall and her novel. Days before the trial, Hall’s solicitors sent a letter detailing the support of May Sinclair, E M Forster, Virginia Woolf and Leonard Woolf, to name but a few (DPP 1/88).

Many famous faces were present at court – as was Radclyffe Hall herself. But she did not speak, because she was not on trial – her novel was. Hall did not want the defense to deny the lesbian content of the text, but rather wanted the focus to be on the literary merit and significance of the book.

Sadly, the Chief Magistrate found the novel’s literary merit to be irrelevant, and on 16 November 1928 ordered that ‘The Well of Loneliness’ be destroyed. Hall was reported to have been visibly devastated by the outcome. Hall and her publisher quickly sought to appeal the ruling, but the original decision was upheld.

A similar trial was to take place soon after in the USA but the court ruled in favour of ‘The Well of Loneliness’, where it continued to be immensely popular. Despite the controversy that surrounded the novel, documents held at the Harry Ransom Center reveal the immense support that Hall received from inspired readers, many of whom related with the plights of Stephen Gordon. One correspondent wrote how ‘It has made me want to live and go on … I discovered myself in Paris and I dreaded this thing which I thought abnormal’[ref]Flood, Alison. ”It Has Made Me Want to Live’: Public Support for Lesbian Novelist Radclyffe Hall over Banned Book Revealed.’ Guardian, 10 January 2019.[/ref].

However, it would be almost 20 years – six years after the death of Radclyffe Hall in 1943 – before ‘The Well of Loneliness’ would be published in the UK once again[ref]In 1949 publisher Falcon Press purchased the rights to an edition of the text without any legal objection.[/ref].

The text remains, to this day, one of the most celebrated lesbian-novels, but has not escaped further criticism. While progressive for its time, Hall’s depiction of ‘invert’ Stephen Gordon has been critiqued for its negative portrayals of lesbianism, its disheartening and hopeless depictions of queer life, and its binary representations of sexuality and gender. However, considering the lack of visibility at the time for queer women and the LGBTQ+ community in general, ‘The Well of Loneliness’ was arguably a crucial starting point.

‘Give us also the right to our existence!’

The Well of Loneliness

It is also important to recognise that there are still issues regarding LGBTQ+ visibility, in the uncovering of queer histories and for LGBTQ+ individuals today. ‘The Well of Loneliness’ and archival documents relating to Radclyffe Hall undoubtedly provide visibility. But Hall’s influence as a prominent middle-class author, as well as the public nature of her identity, are what enable us to research her today[ref]Souhami writes, ‘It is doubtful whether Radclyffe Hall and Una … and the rest, with their fine houses, stylish lovers, inherited incomes, sparkling careers and villas in the sun, were among the most persecuted and misunderstood people in the world.’ (‘The Trials of Radclyffe Hall’, 1998, p. 181-2).[/ref]. Without the same privileges as Hall, many LGBTQ+ individuals from the past would have kept their sexuality or identity a secret due to the cultural attitudes of the time. Thus, sadly, the lives of many queer people remain hidden.

Thank you to the Cadbury Research Library: Special Collections at the University of Birmingham for providing images from their collection of Radclyffe Hall’s love letters. If you are thinking of researching LGBTQ+ history and want to help provide visibility for queer individuals and experiences from the past, take a look at this Sex and Gender Research Guide.