A thought that may have crossed your mind when reading the title of this blog is ‘Why would we want a computer to read in the first place?’ The answer to this is that, despite the overwhelming size of The National Archives’ Discovery catalogue, there is so much more information out there! Computers can help us reveal this previously hidden information.

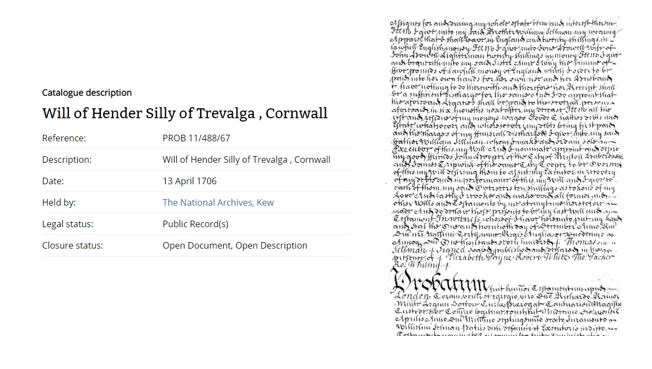

Take, for example, PROB 11, a vast set of registered copy wills from the Prerogative Court of Canterbury. These range in date from 1384 to 1858 and contain a wealth of information about places, beneficiaries, family, relationships, goods, religion, values and land, to name but a few. Whilst one will can contain information on multiple people, the catalogue description only shows the will maker, place and a date, making the rest tricky to search. With 2,000 volumes each containing thousands of pages, adding the extra information would be an enormous task for volunteers, to either extract the more complex data or transcribe the documents. It is in these scenarios that we could really use some help.

An example of a will from the PROB 11 collection compared to its catalogue description

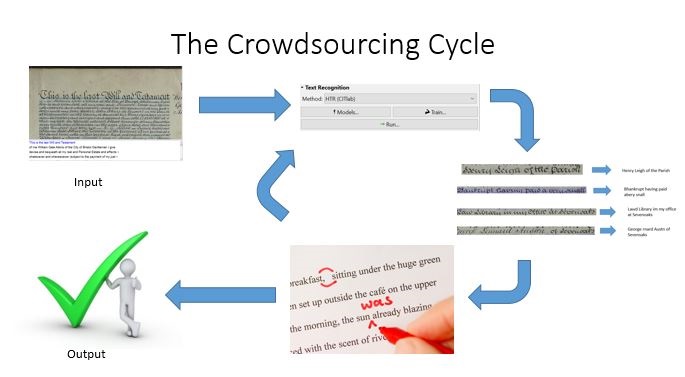

Recently I completed an Early Career Fellowship at The National Archives, the first to be very generously sponsored by the Friends of The National Archives. The position was part of the Digital Research Team, helping with one of their current research projects, namely the transcription of PROB 11 using machine learning. The topic was suitably broad, looking at ways of crowdsourcing in conjunction with the processes of the handwritten text recognition software, Transkribus.

Transkribus is software that anyone can download, which can read handwritten documents. To do so, it requires full transcriptions of a sample of documents. The sample documents and transcriptions are given to the software which then creates a model of the handwriting, which it can use to read further examples of this specific style of handwriting. Once results start being generated from the model we can improve the accuracy by correcting it, producing better and better results.

The Crowdsourcing Cycle

When it comes to learning, computers are very similar to humans: more examples and more experience make them much better at reading. If you ask a computer to read a style of handwriting it hasn’t seen before, it probably can’t, and words that it sees less frequently are less likely to be correct. This is why collections such as PROB 11 are perfect to trial with this type of software, as they are very formulaic and the handwriting style is consistent.

But how can we help? There are two points of human input in the whole process – the full transcriptions at the very beginning and at the correction stage. A lot of people enjoy transcribing documents but correction is seen as a more mundane task, which is not as much fun. However, from an efficiency perspective it takes much less time to correct documents. A large part of this research project was about making correction more enjoyable and easier for the user, looking at their key motivations to transcribe documents. This research can be divided into three key areas.

Table showing user motivations to transcribe documents

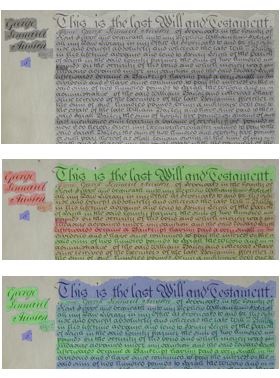

The first key area was to find a way of visualising correction on a large screen. To isolate areas most likely to be incorrect and make them easier to find, we used Natural Language Processing to generate probabilities of how likely Transkribus was to be wrong. Then using these probabilities we highlighted particular lines that needed the most correction so that users could specifically target them. A lot of fun was had using different colours for the highlighting.

When looking at motivations to transcribe documents, volunteers often enjoy knowing the context and history behind the work they are doing. By displaying a full page there is the opportunity to not only correct but also to read the full document.

The second area was based on an overview look at crowdsourcing projects across multiple sectors. The most exciting projects had two or more volunteer motivations behind them. For example, a project where a group go for a run and also paint a community centre, both helping the community but also encouraging fitness and the social life of the participants. Volunteering through which the participants learnt or developed skills was also highly successful.

Another big factor was time-saving initiatives. If you can do two or more things at the same time then it was more likely to be successful. Crowdsourcing and volunteering should fit in to people’s lives and the rise of micro-volunteering initiatives demonstrates that.

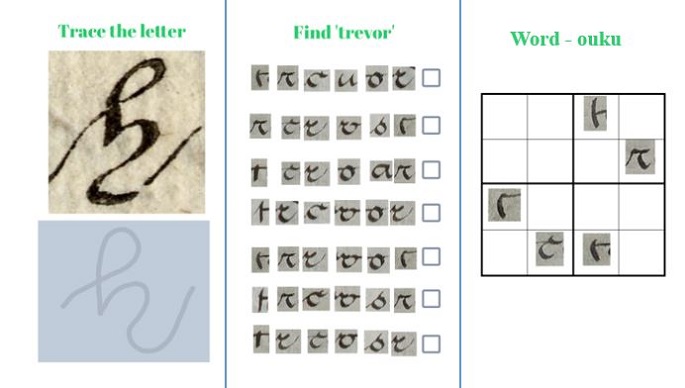

The average UK citizen spends around about an hour commuting each day. As a result we did some research into the idea of apps and transcription on the go with the additional purpose of being able to teach the user palaeography at the same time. We created a demo version of an app called ‘Many Hands’, which gives the user exercises to improve their palaeography skills on the move whilst also correcting transcriptions from Transkribus.

Documents from the PROB 11 collection highlighted to demonstrate potential inaccuracies

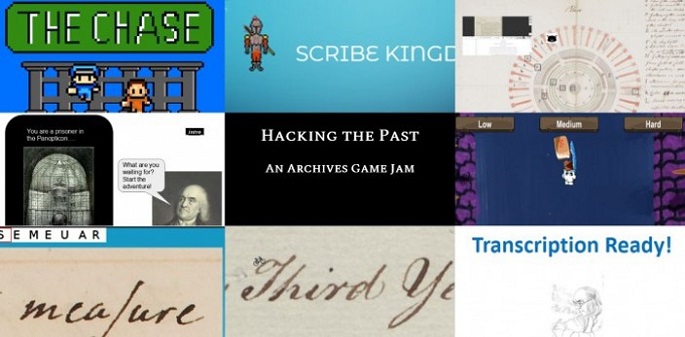

Finally, we looked closely at ways to make transcription fun for those who might not know about it at all. As a result we ran a Game Jam with the Transcribe Bentham Project at University College London (UCL) and the UCL Innovation and Enterprise team earlier this year. Further details can be found here and here in previous blog posts. The aim of the Game Jam was to make the process of correcting and transcribing more fun and efficient. Around 55 people attended with a variety of interests and perspectives, ranging from academics to game designers, and made some amazingly inventive submissions. The winning submission was a version of the game Frogger, where the player has to dodge and transcribe criminal records from HO13. See the results for yourself! It was a great success and we came away not only with lots of fantastic new ideas, but with confidence that transcription can be fun for everyone!

Our game jam entries

A big thank you to the Friends of The National Archives for supporting this research, and the staff at UCL and the Transcribe Bentham Project, specifically Dr Louise Seaward, who made it possible for the game jam to take place.

This all sounds very good but it will only repeat what is in the document, even if it has a spelling that is wrong. Of course a computer will not tell you what is in a collection of papers, i.e. it will not tell you any items that are of use to researchers when it has a general description, rather than a document whose content is known, e.g. ‘the will of … of Probus, Cornwall’ and a date and is a single document. For me humans transcribe (mostly) correctly and should transcribe logically.

I think it is a lovely project and will aid research into a number of topics that use wills. All power to your elbows. I can’t wait to see when the software can be rolled out to county records offices and applied to their wills too.