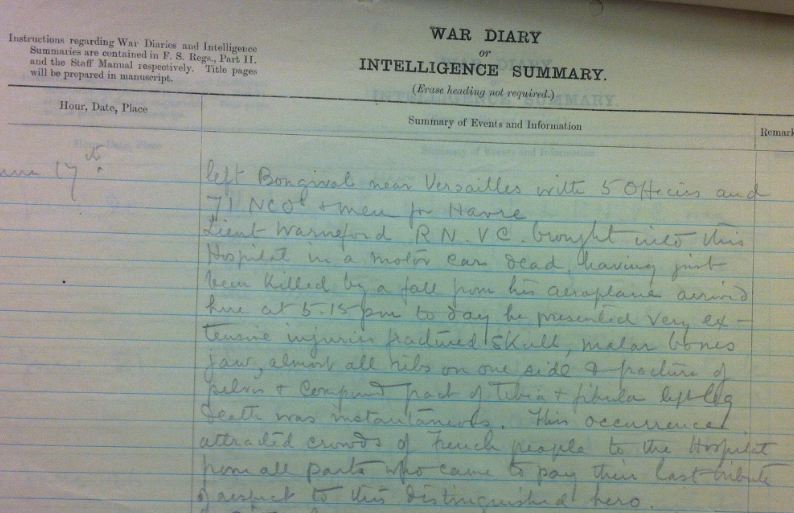

Whilst looking in the war diary of the 4th General Hospital in Versailles (WO 95/4076) for something else entirely, I came across an entry for 17 June 1915 that really moved me. It relates to a Victoria Cross (VC) winner, Lieutenant Warneford, who had been killed in an accident and brought to the hospital. The description of his injuries and of the reaction of the local people drew me in:

‘Lieut Warneford RN VC brought into this hospital in a motor car dead, having just been killed by a fall from his aeroplane. Arrived here at 5.15pm today. He presented very extensive injuries: fractured skull, malar bones, jaw, almost all ribs on one side and fracture of pelvis and compound fract[ure] of tibia and fibula left leg. Death was instantaneous. This occurance attracted crowds of French people to the hospital from all parts who came to pay their last tribute of respect to this distinguished hero.’

On 20 June the diary entry reads: ‘The body, in coffin, of Lieut Warneford RN VC was covered with wreaths from various donors and on view to the public who proceeded to the church tent in many hundreds. A large number of magnificent wreaths were presented and placed around the coffin.’ Then on 21 June: ‘A Naval Officer came this morning and took away the coffin and wreaths which all were sent to England at 6am.’

Using a combination of Discovery, our catalogue, and Google I discovered that on 7 June 1915 the 23-year-old Reginald (Rex) Alexander John Warneford had destroyed a German Zeppelin airship over Belgium. This had involved chasing the Zeppelin in his Morane Monoplane (a flimsy looking aircraft to modern eyes) until he could climb above it and drop his bombs onto it. After hitting his target, the explosion caused his own aircraft to overturn and its engine to cut out. Warneford made an emergency landing in enemy territory and, so the story goes, fixed his fuel line with a cigarette holder and flew home.

The British press went crazy for the story and Warneford was feted as a hero. One newspaper cartoon, under the title ‘The Top Dog’, showed Warneford’s plane as a winged British bulldog dropping a bomb onto a German Daschshund with the body of an airship. The press also printed a poem by Belgian poet Emile Cammaerts (grandfather of British author Michael Morpurgo), part of which, when translated, reads ‘Being one against a hundred. Fight like a hornet against a giant’.

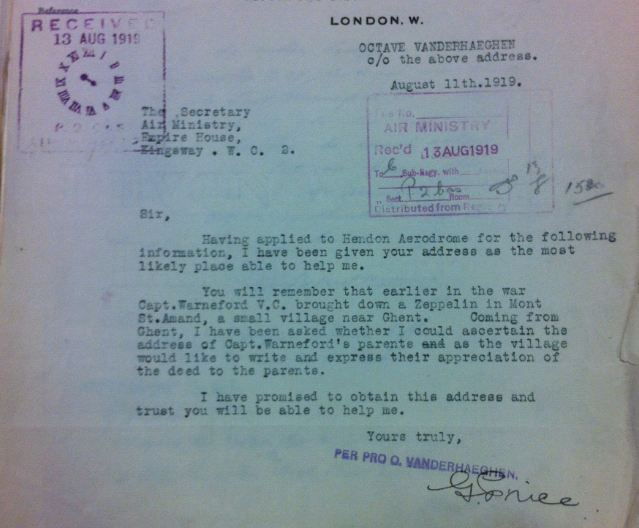

The burning wreckage of the Zeppelin landed on the Grand Béguinage de Saint Elisabeth, one of the best known convents in Belgium, which was also home to women and children refugees. A newspaper reported that ‘Terrible scenes followed. Many of the crew were already dead, and their bodies were flung about in all directions. Not one man survived. In the Béguinage fire two nuns were killed. A brave man lost his life in attempting rescues. With a child in his arms he leaped from the burning room, and both were killed.’ Despite this, the local people were so grateful to Warneford that on 11 August 1919 a representative wrote to the Admiralty to try and make contact with his parents so that the villagers could pass on their thanks.

Warneford was awarded the VC on 8 June. The telegram from the King said: ‘I most heartily congratulate you upon your splendid achievement of yesterday, in which you, single-handed, destroyed an enemy Zeppelin. I have much pleasure in conferring upon you the Victoria Cross for this gallant act’.

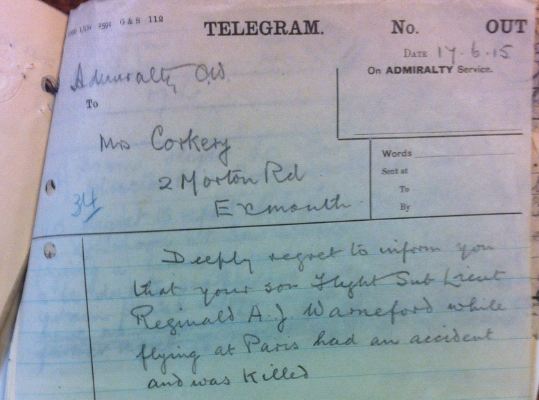

Ten days after destroying the Zeppelin, and only hours after receiving the Legion d’honneur from the French, Warneford was on a test flight with a passenger, American journalist Henry Needham. The aircraft suffered catastrophic failure of the airframe and crashed, killing both men.

Again, there was widespread press coverage. Arrangements for the repatriation of Warneford’s remains were published and one newspaper reported that ‘A vast crowd waited patiently outside Victoria Station last night to pay a tribute to the memory of Lieut Warneford. Women wept and men were deeply moved as the body of the heroic young airman was placed on the gun-carriage’.

The Daily Express campaigned to raise funds for a memorial to Warneford in Brompton Cemetery which was unveiled on 11 July 1916 with a Guard of Honour from the Royal Naval Air Service. In addition, a memorial tablet was erected in Highworth Church, Wiltshire by 62 members of his extended family.

The National Archives has Warneford’s service record in ADM 273/8/193 and letters and reports relating to his death in ADM 137/4820. Unusually, there are also some private papers in our collection. These are in PRO 30/71 and relate to Guy Warneford Nightingale, Rex Warneford’s cousin, who served in Gallipoli and on the Western Front with the Royal Munster Fusiliers. Amongst the papers is a scrapbook of newspaper cuttings about Rex, seemingly collected by Guy’s sister, Margaret Warneford Nightingale, in PRO 30/71/7. I should stress that The National Archives is a government archive which collects official records and it is very rare for donations of personal papers to be accepted into its collection. I imagine it was Lieut Warneford’s fame that made these papers of interest.

Having researched the events around Warneford’s VC and untimely death, I came across two other cases of VC winners who, coincidentally, also died at the age of 23. Look out for later blogs on James McCudden, who received more awards for gallantry than any other British airman in the First World War, and William Leefe Robinson who was the first pilot to shoot down an airship over Britain.