In 1969 the Central Office of Information (COI) made a film about a scheme to improve relations between police officers, teachers and social workers, and British communities of people from former colonies. The scheme was funded by the Commonwealth Foundation, which is described in the film as ‘an organisation that exists to promote simple harmony and professional interchange between men and women throughout the Commonwealth.’[ref]The Commonwealth Foundation today describes itself as ‘the Commonwealth’s agency for civil society. We support people’s participation in democracy and development’.[/ref]

This blog takes a look at the film and explores the files at The National Archives that tell us more about the scheme.

‘Commonwealth Foundation’

The film is called ‘Commonwealth Foundation’ and you can watch it free of charge on the BFI player. It’s just a little over 12 minutes long and opens with scenes of Brixton market and the following commentary:

‘Brixton, a large multi-racial community in south London with a big West Indian population. Many arrived over 20 years ago to carve out new lives for themselves. Many born since have never even seen the Caribbean. A whole lifestyle developed in the West Indies is totally different from that of Britain, and the problems of adjustment have been formidable. Lesley Hawkins is Chief Inspector of Brixton Police. Law enforcement is never easy, but in an immigrant community it’s doubly difficult. Not that there’s more crime, but there are bound to be more misunderstandings. If he were to succeed in Brixton, his work had to become highly specialised. He had to get to really know and understand the immigrants’ problems.’

The film goes on to show members of the Commonwealth Foundation in Marlborough House in central London, and explains that the organisation is ‘financing a series of informal trips to various parts of the Commonwealth, chiefly India, Pakistan and the Caribbean, by Britons working amongst large immigrant communities’.

Chief Inspector Hawkins is one of the people taking up the opportunity offered by the scheme, but before he goes on his trip the film shows him with a Brixton family in their living room, where the mother of the family explains one of the difficulties faced by immigrants to the UK: ‘It’s said that West Indians don’t take part in the community, or community life, or community work. But I think it is for the population, the indigenous population to, you know, to do something to attract us to come out. I mean, after all, we are in a strange country. If you go to a strange country you don’t just hop out and start taking part in what’s going on. You’ve got to be invited out.’

The film shows Chief Inspector Hawkins during his two months in Trinidad, getting to know the place and the people. The Commonwealth Foundation scheme didn’t involve set itineraries, but instead encouraged informality, leaving the participants free to pursue their own particular objectives, talking to people whenever and wherever was appropriate for them.

‘The need to know took the Chief Inspector to every corner of Trinidad and Tobago; talking and, more important, listening to people in every walk of life. Stopping them on the sands or in the streets, exploring the jungles with them, or simply worshiping together in a Sunday chapel.’

In general, the film portrays a surprisingly forward-thinking attempt by the Metropolitan Police to learn more about the communities it served so as to improve relations with them. However, at times it also perpetuates stereotypes in remarks such as ‘The West Indian is traditionally happy-go-lucky with a history of peace and gaiety under the sun’ and ‘It’s the West Indian’s lust for living, for parties, dancing and loud music that is at once his great strength and weakness miles from home’.

Travelling bursary scheme

The National Archives has files relating to the Commonwealth Foundation bursary scheme, which give information about how and why it was developed, what the participants learned from it and how they used that knowledge when they returned to their professional roles in the UK.

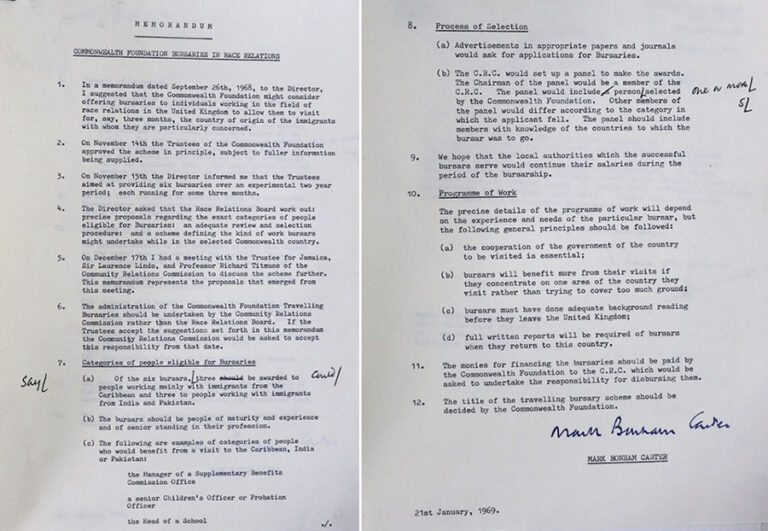

One file, titled ‘Commonwealth Foundation Bursaries’[ref]Commonwealth Foundation Bursaries. Catalogue ref: CK 2/319.[/ref], contained papers relating to the setting up of the scheme and correspondence between applicants and the organisers. Mark Bonham Carter, Chairman of the Race Relations Board, had met with Sir Laurence Lindo[ref]Sir Henry Laurence Lindo was the Jamaican High Commissioner from 1962 to 1973.[/ref], High Commissioner for Jamaica and Trustee of the Commonwealth Foundation, and Professor Richard Titmuss[ref]Professor Richard Titmuss was a pioneering British social researcher and teacher who was also active in the British Eugenics Society. [/ref] of the Community Relations Commission[ref]The Community Relations Commission was set up under section 25 of the 1968 Race Relations Act (www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1968/71/section/25/enacted).[/ref] to discuss setting up the bursary scheme. Following the meeting, Bonham Carter drafted a memorandum outlining the purpose of the bursary scheme, who could apply, and how it would be run.

The memorandum shows that the bursary scheme was to be administered by the Community Relations Commission, and that the six successful applicants would travel to the Caribbean, India and Pakistan. The recipients of the bursaries should be ‘people of maturity and experience and of senior standing in their profession’ such as the Head of a school, a senior probation officer or the manager of an office dealing with claims for unemployment benefits.

Applications were to be assessed by a panel made up of representatives of the Community Relations Commission and the Commonwealth Foundation, along with people familiar with the professions of the applicants and the countries they would be travelling to. Before they took their trip, successful applicants needed to prepare by reading appropriate background material, and on their return they would be expected to write a full report.

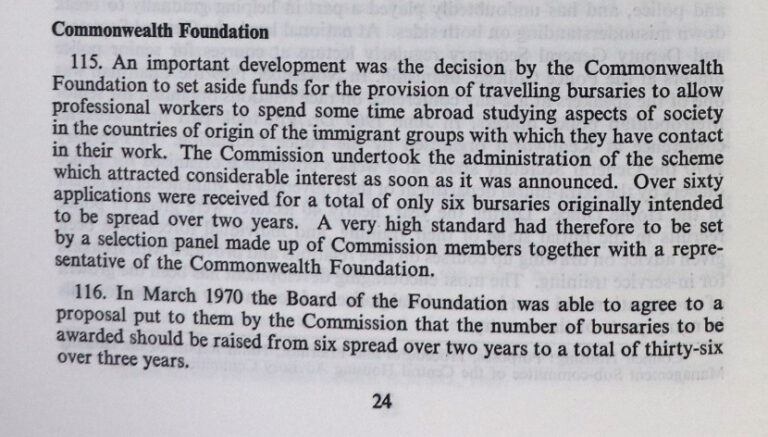

Bursary scheme places increased

Another file at The National Archives, with the title Community Relations Commission[ref]Community Relations Commission. Catalogue ref: CK 1/12.[/ref], contained a copy of the annual report of the Community Relations Commission from 1969-1970. Within the report was a small section about the Commonwealth Foundation bursary scheme which explained that 60 applications had been received for the initial six bursaries, and that the Commonwealth Foundation had agreed to increase the total number of bursaries to 36 over a three-year period.

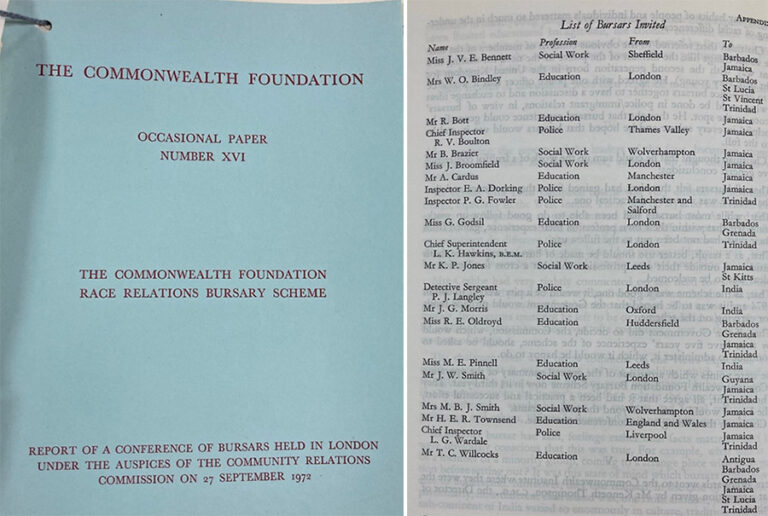

Conference for recipients of bursaries

A third file, Police Liaison with Community Relations Commission[ref]Police liaison with Community Relations Commission. Catalogue ref: MEPO 2/11239.[/ref], included a report from a conference in September 1972, when the scheme had been running for almost three years. Past and present recipients of the bursary came together with members of the Community Relations Commission and representatives of organisations closely connected with the scheme such as the Metropolitan Police, National Union of Teachers, and Central Council for Education and Training in Social Work.

The conference ‘recorded the impressions of bursars and discussed the best way by which these impressions could be communicated’. Proceedings opened with an introduction by Mark Bonham Carter and general remarks from bursars, including comments by Chief Superintendent Hawkins about his experience in Trinidad:

‘by seeing ordinary people in their own surroundings he had learned a great deal about family life and social backgrounds and, as a result, he now felt himself less inhibited when talking to immigrants from the West Indies. They, on their part, appeared to have noticed this change because there was now more rapport between them. He added that he was now being invited to take part in discussion groups and this had a very great practical value in his daily work.’

The conference attendees split into four study groups for more intensive discussions around four questions:

- What moral did each person draw from their visit?

- Did community relations look different since they returned?

- What else could be done?

- How should the bursaries be followed up?

The thoughts and conclusions of each group make fascinating reading. There was agreement that visiting and living with the communities in the host countries gave the bursars an intimate understanding and appreciation of the values and attitudes of immigrants from the same places, and that this in turn helped them to appreciate some of the difficulties they faced. There was also a strong sense that good community relations depended on personal contact and that ‘it was only by increasing such contact socially, at work and indeed in all respects, that greater tolerance and understanding could be developed’.

Conclusion

The film, together with the files at The National Archives, are an example of a surprisingly creative and collaborative approach to improving race relations in the years following the 1965 and 1968 Race Relations Acts. Thanks to funding from the Commonwealth Foundation, the support of local authority employers and the administrative support of the Community Relations Commission, the scheme appears to have been of great benefit to those who were chosen to participate, and hopefully to the communities they worked with.

More government sponsored films

The film ‘Commonwealth Foundation’ was made by the COI, the government’s ‘communications agency’. This year (2021) marks the 75th anniversary of the COI which used films, posters and leaflets to educate, inform and influence the public between 1946 and 2011. The National Archives has been working with the British Film Institute (BFI) and the Imperial War Museums (IWM) to highlight some of the many thousands of films made by the COI.

You can watch more COI films on the BFI player, the IWM films website and on The National Archives website. You can read more about the COI on my earlier blog, Connecting collections amid COVID-19, written together with the BFI and the IWM, and by searching on Twitter for #COI75.