The immediate effect of the Easter Rising in 1916 was to stimulate support for the Home Rule movement, and not to create support for the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB), the Irish Volunteers or Sinn Fein. (Find out more about the aftermath of the Rising in my previous blog post.) If the leadership had been able to capitalise on this, perhaps matters would have developed differently, but they were focused on parliamentary comment so much that they risked becoming out of touch with opinion in the nationalist and Home Rule camp.

The negotiations over Home Rule with Lloyd George in summer 1916 only highlighted the inability of the Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP) leaders, John Redmond and John Dillon, to secure an agreement. The effects of this were to take time to work through.

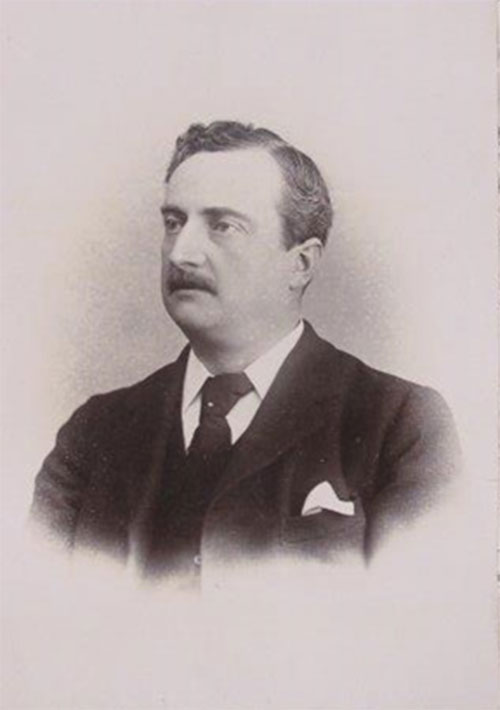

John Redmond, leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party, in the 1900s (catalogue reference COPY 1/447/38)

The IPP was able to see off its pro-Sinn Fein rivals in the ensuing West Cork by-election of 15 November 1916, which was won by the IPP on a swing away from the All-for-Ireland League.

As the frustration (for Redmond) of the summer negotiations became more apparent, organisations such as the new Anti-Partition League – soon renamed the Irish Nation League – were set up, reflecting the development of a new and more militant strand of the Home Rule movement. A fringe of Catholic priests began to attend Sinn Fein meetings. A new mood began to take hold.

In the autumn the casualty lists from the battle of the Somme began to be released. This created a shock across Ireland, including among the Catholic nationalists who had supported Redmond’s argument that the Irish Volunteers should fight in the British Army in order to prove their loyalty and win Home Rule. Taken with the results of the summer negotiation, it seemed that, although Irish people were expected to fight in the British Army, this would not necessarily lead to a solution to the question of home rule.

In December 1916 and early 1917, the Easter Rising prisoners began to be released. As it became clear that the British might introduce conscription in Ireland to support the war effort, the IRB became active in a new direction. Agitation against conscription became linked to electoral campaigning for Sinn Fein candidates who were opposed to conscription and uncompromised by the IIP’s attempts to negotiate Home Rule.

The North Roscommon by-election was held on 3 February. It was won by the Sinn Fein candidate Count Plunkett, father of Joseph Plunkett, who was shot for his role in the Easter Rising.

A national convention or Irish Assembly was convened at the Mansion House on 19 April 1917 under the auspices of Count Plunkett, to clarify which policy would drive the national movement: republicanism reinforced by physical force, or Arthur Griffith’s and early Sinn Fein’s less radical dual-monarchy strategy.

CO 904/196 Dublin Castle Papers Personalities Files, Michael Collins

Delegates from 70 public bodies – including Board of Erin, Cumann na mBan, National Aid Association, Irish Nation League and the Irish Volunteers – and 1,000 delegates, including 150 clergymen and members of Count Plunkett’s Liberty Clubs, were there in numbers. (Plunkett had set up the clubs after the election to espouse the republican cause, which he believed Sinn Fein was not committed to.)

The meeting proved inconclusive, the delegates at the Mansion House failing to unite around a single programme. A committee was set up to pursue this. At the conclusion, the conference released a compromise declaration, partly based on the 1916 Proclamation, which acted as a kind of halfway house between the militant Home Rulers and the separatists, around which both could unite.

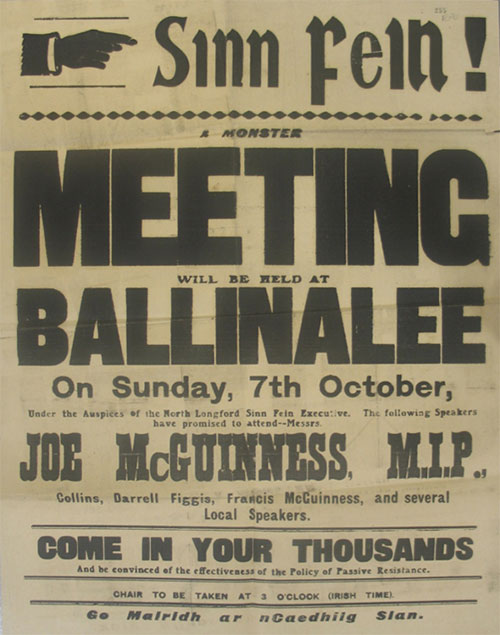

On 10 May, the Sinn Fein candidate Joseph McGuinness (still a prisoner in HM Prison Lewes after the Easter rising) won the South Longford by-election. The shock narrow victory was a political disaster for Redmond and the IPP.

Having tried to broker a deal, Lloyd George tried next to delegate the discussion to elements from both the nationalist and Unionist camps. This was to prove equally problematical.

However, before it could happen, the East Clare by-election was held on 10 July following the death of the MP – Willie Redmond of the IPP, who was killed in millitary action at Thiepval. The seat had been held by constitutional nationalist MPs since its creation in 1885, and Redmond had been unopposed in every election since 1900. But this time the by-election was won by the Sinn Fein candidate, Eamon de Valera, who had campaigned in the military uniform of the Irish Volunteers. De Valera also appealed to the electorate by having Catholic priests preside over his meetings.

The Irish Convention sat in Dublin from 25 July 1917 until March 1918 to address the Irish question and other constitutional problems.

Although there were elements among both Nationalists and Unionists that were prepared to make compromises, the two main camps stood their ground in terms of mutual incomprehension of the others’ political wants and needs.

Edward Carson, leader of the Irish Unionists (catalogue reference COPY 1/430/74)

Some participants considered ways in which separate parliaments for North and South could be created, and affiliated to an Imperial Parliament in London – although this was not to be successful in creating a Home Rule Ireland bound by mutual interest. The Nationalists could not see why a single, unitary, Home Rule state could not be created. The Unionists remained aghast at the possibility of a unitary state in which the established church was the Roman Catholic Church, and in which ties with Britain were loosened.

The Convention, intended to allow for the creation of common ground, was a failure in that it simply served to harden attitudes.

The Kilkenny City by-election was held on 10 August 1917. It was won by the Sinn Fein candidate W T Cosgrave, another prisoner of the Easter Rising

Throughout this, the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) worked heavily within the Liberty Clubs for Sinn Fein electoral campaigns. Later in 1917, they were able to attend the re-foundation conference of Sinn Fein, at which de Valera became President. They were able to have the Liberty Clubs amalgamated into Sinn Fein and to gain representation on the Sinn Fein Executive.

The stage was set for a complete re-orientation of the nationalist movement, with Sinn Fein as the focal point and the IRB deeply involved in both the campaigns and the leadership of the new party.

With Sinn Fein’s electoral victories underlining its new-found position in relation to the broader movement, and its gradual overtaking of the IIP in individual by-elections, the ground was being laid for a more general political contest and confrontation within the nationalist movement which would change the course of Irish history.

This blog is part of an occasional series of blogs and articles outlining the course of events in Ireland during the period of the struggle for independence, 1910 to 1923.

- Read the previous post, Ireland after the Easter Rising

- See our research guide to Ireland’s Easter Rising, 1916 for further sources for this period