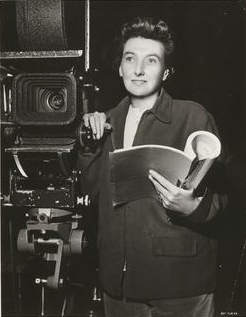

From papers and photographs to posters and maps, The National Archives’ collection contains over 1,000 years of iconic government and public records. However, what you may not know, and what can often be overlooked, is that The National Archives can also provide unique insights into the history of film and the film industry. In this blog, Josephine Botting, a curator at the BFI National Archive, and Sarah Castagnetti, Visual Collections Manager at The National Archives, take a look at government files that tell us about the work of Britain’s most prolific female commercial director, Muriel Box.

During the Second World War, British cinema was a vital tool in the government’s efforts to keep up morale. The messages of the propaganda machine – to keep calm and carry on, to do your bit – were put across in public information films but also, more subtly, through entertainment features, which showed the bravery of the fighting forces as well as the women who kept the country ticking over.

But once the war was over, producers wasted no time in bringing the seedier side of life to British screens with films presenting characters, particularly female, in stark contrast to the wives and mothers who’d upheld morale and morals in our hour of need. The post-war British landscape of rubble-strewn bombsites was a perfect backdrop for crime dramas, while the ‘spiv’ culture that thrived due to the continued austerity and rationing provided the kind of sensationalism that audiences were craving. This rash of crime films raised concerns in the government.

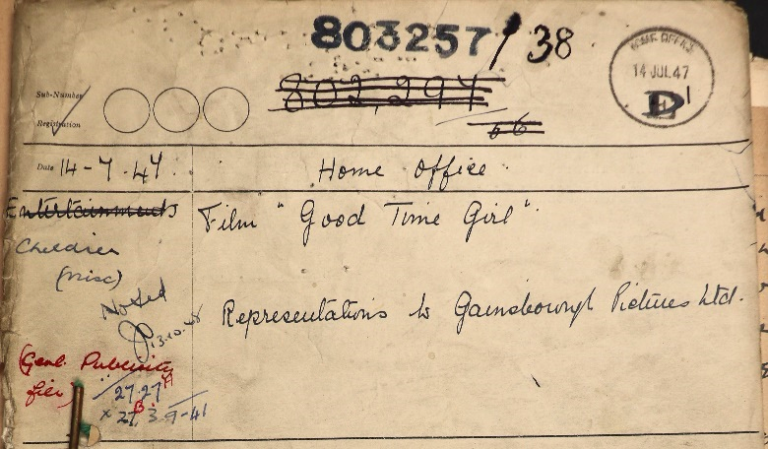

Files held in The National Archives contain correspondence about two post-war films that came to the attention of the state for very different reasons. Both carried the mark of Muriel Box: Good-Time Girl (1948) which she co-wrote, and Street Corner (1953) which she co-wrote and directed.

Good-Time Girl follows the story of 16-year-old Gwen Rawlings who leaves her unhappy home life, falls in with small-time criminals and ends up being sent to an ‘approved school’ by the juvenile court. Here, Gwen gets involved in a fight, is seen drinking, smoking and intimidating a younger girl, and finally absconding during a riot in the dining hall. After further escapades, she meets two deserters from the American army and gets mixed up in a murder. The full film is available to watch free of charge on BFI player (UK only).

The files at The National Archives deal mostly with the reaction to the way the film portrayed the approved school. These were institutions run by the Home Office, where young people who got into trouble were sent by the juvenile courts. The idea was to remove them from bad influences and deprived or dysfunctional home lives, giving them education and training in the hope that they would choose a different path.

For some young people the approved school system offered security and comforts they hadn’t had before, but the courts didn’t send juveniles to approved schools in equal measure. After a first offence, most boys received a fine which could be followed by other interventions if they offended again. For girls, a first offence was most likely to result in being sent to an approved school straight away. The courts saw this as a way to protect girls’ moral well-being – a concern that didn’t seem to apply equally to boys.

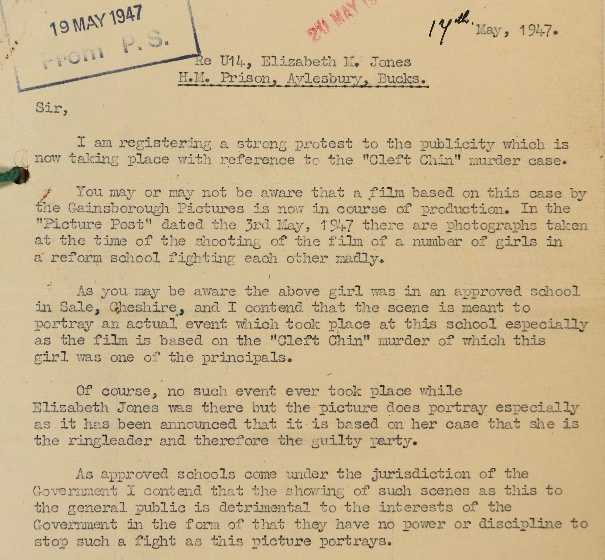

In May 1947, before Good-Time Girl was released, the Picture Post featured a double-page photo spread with images of the dining hall riot taken during filming.

The article prompted two main concerns. Firstly, the approved school was depicted as a place where girls, far from being rehabilitated, appeared to be further corrupted by their fellow inmates. Secondly, the magazine explicitly linked the film with a 1944 real life case known as the ‘cleft chin murder’ which had been committed by a young waitress, Elizabeth Jones, and an American deserter, Karl Hulten.

Elizabeth Jones had herself been sent to an approved school after running away from home at the age of 13. Later, at the age of 18, she met Hulten, and together they committed a series of crimes culminating in the murder of taxi driver George Edward Heath[ref]Files relating to the murder of George Edward Heath and the trials of Elizabeth Jones and Karl Hulten are held at The National Archives.[/ref].

One of the government files[ref]MH 102/1137.[/ref] contains a letter to the Home Secretary, James Chuter Ede, written with the permission of the parents of Elizabeth Jones, objecting to the making of a film with obvious parallels to her case. Another file[ref]MH 102/1138.[/ref] includes a letter from the Newcastle Upon Tyne Standing Conference of Women’s Organisations which states:

‘it is felt by people dealing with the delinquent girl that this film gives a completely untrue picture of their treatment and will be extremely harmful to any young people seeing it’

The Home Office contacted the production company and made arrangements for representatives to see the finished film, make notes and report back. Their conclusions did nothing to allay Home Office concerns since the consensus of opinion was that the scenes in the approved school were ‘a complete travesty of the truth’.

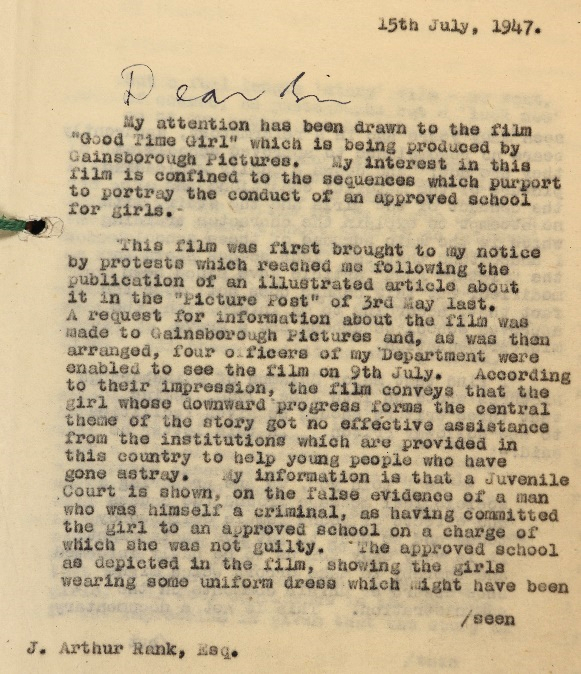

The Home Secretary wrote to J Arthur Rank[ref]MH 102/1139.[/ref], head of the Rank Organisation which was financing and distributing the film, to raise his concerns about the approved school scenes. He expressed his disappointment that

‘the film conveys that the girl … got no effective assistance from the institutions which are provided … to help young people who have gone astray’ [and] ‘bears no resemblance to approved schools as they are now; and draws a wholly misleading picture of the girls and the staff’

The film’s producer, Sydney Box, wrote an extra scene to try and offset the damage; in it, a matron appeals for more and better teachers to apply to such schools. This actually made things worse by implying there was inadequate staffing, which of course was the responsibility of the Home Office. The association with Elizabeth Jones was equally hard to tackle since raising the matter would draw more attention to it and probably cause her parents more distress.

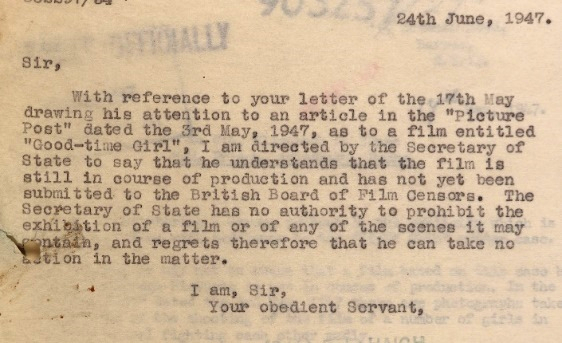

The Home Secretary was asked by various different parties to consider banning the film but he had no authority to do so. Nevertheless, Sir Alexander Maxwell of the Home Office met with Sir Sidney Harris of the British Board of Film Censors to consider whether there were proper grounds for refusing to pass the film. Although they both felt the film was damaging to the efforts of approved schools and juvenile courts, they couldn’t justify rejecting it on the grounds that it misrepresented the approved school system or that it drew a link with Elizabeth Jones.

One or two local authorities did ban the film but the publicity this generated risked creating more of a buzz and encouraging film-goers to seek it out. J Arthur Rank was a very religious man from a Methodist background and he maintained that the aim of the film was to educate the country’s youth about the dangers of pleasure seeking; conversely, it was the view of some women’s groups that the film revelled in Gwen Rawlings’ decadent lifestyle.

The debates around Good-Time Girl indicate that the government felt cinema could lead the impressionable astray. But a file about Street Corner (1953), Muriel Box’s second film as sole director, shows that film was also recognised as a useful tool for influencing public opinion in government’s favour.

Street Corner was produced by Muriel’s husband, Sydney Box, and followed the work of women officers in London’s Metropolitan Police force. Muriel was the only female British fiction director at the time, though there were several women involved in documentary film-making. There was a notion that only certain subjects were suitable for women directors, and the women’s police force was clearly one of them.

Perhaps due to the controversy stirred up by Good-Time Girl, Sydney Box sought approval from the authorities in good time before starting the project. As well as maintaining good relations, he needed police support to ensure accuracy and to keep the budget down by providing access to locations and equipment.

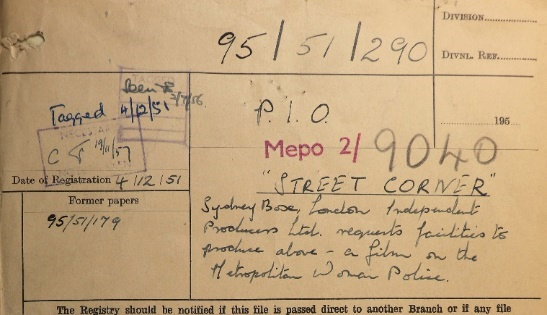

Collaboration on Street Corner began in early December 1951 with the Police Commissioner laying out the conditions on which assistance would be given. One key stipulation was an involvement at the script stage, which led to a great deal of negotiation as the producer’s desire for lurid and melodramatic events came up against the police commissioner’s insistence on authenticity.

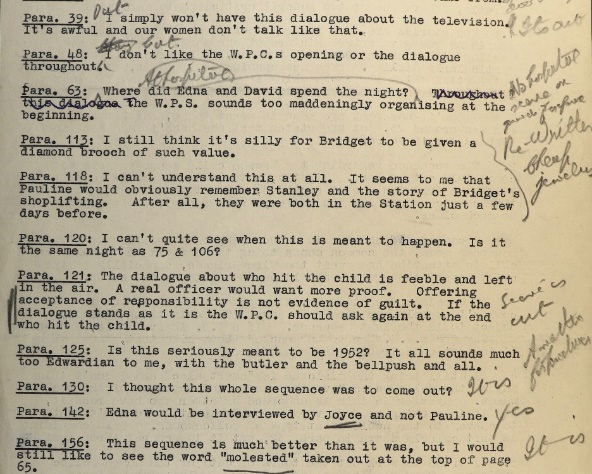

The National Archives’ file includes no less than four treatments and various script iterations peppered with comments from the Met’s Public Information Officer, Percy Fearnley, and Chief Superintendent Elizabeth Bather, who were keen to facilitate a realistic and sympathetic portrayal of modern policing.

One report on the script noted that ‘the stories are, in the most part, so completely improbable and in no way give a true picture of our work’. The scriptwriters were felt to be heavily influenced by Hollywood gangster films: ‘the dialogue is “smart alec” and I don’t think any of the policewomen have the manner and approach of the real women.’

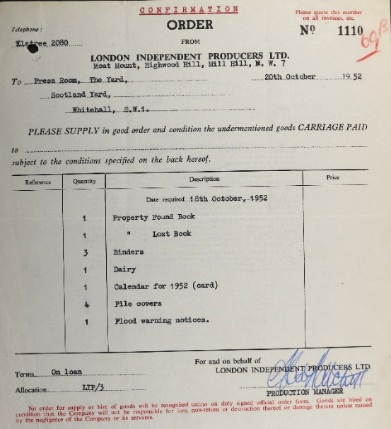

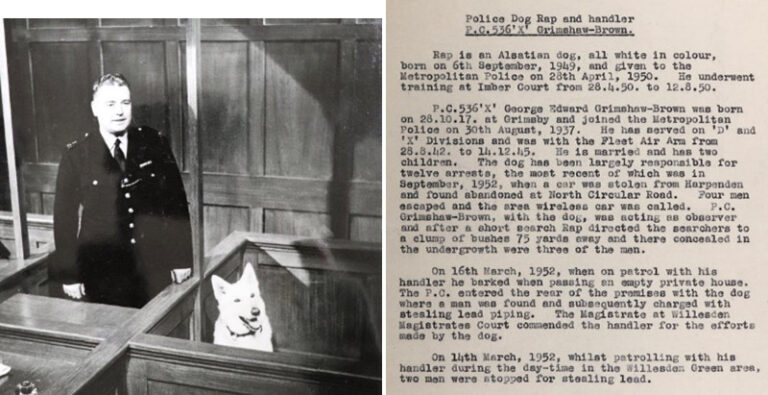

The film production company was assigned a female police officer as an advisor and requested the loan of props and equipment such as radio cars and uniforms, and the inclusion of a rather handsome three-year-old Alsatian police dog called Rap was suggested by the force itself, with a dramatic scene written in for him.

The Met had formed its first dog section in 1946 with six Labradors, adding Alsatians a couple of years later. By 1950 there were 90 trained dogs in the Metropolitan Police. Rap and his handler, PC George Grimshaw-Brown, provided a short CV of their partnership which showed that Rap had assisted in 12 arrests since finishing his training. Rap’s appearance was in a climactic chase scene as the lead villain, Ray, played by Terence Morgan, tried to escape across a London bomb site but was caught by the intrepid dog.

One of the Commissioner’s reasons for supporting the production was the hope that the film would paint the police in a positive light and help recruit more women to the force, hence his desire for accuracy rather than depicting it as a glamorous occupation. Just as women film directors told ‘women’s stories’, female police officers mainly dealt with women and children who got involved with the law and the events concocted for Street Corner include a young mother caught shoplifting, a female army deserter guilty of bigamy and a neglected toddler. In each case, the female officers demonstrate their compassionate side by trying to get to the heart of the social problem behind the crime, rather than demonising the guilty.

Whether or not Street Corner was a successful recruitment tool is not recorded but the files held by The National Archives tell a fascinating story about the state’s views on cinema and its attempts to control it, whether for damage limitation or promotion of its own aims.

.

Thank you, Sarah and Jo, for this very informative and fascinating blog.

My impression from looking at the MEPO files a few years ago was that there was a very gendered discourse around the Met’s response to Street Corner. The script treatments were compared unfavourably to The Blue Lamp, which was seen as more realistic in contrast to the melodramatic treatment of Street Corner. Interesting that the association between melodrama and *women’s pictures* found its way into the Metropolitan Police as well as the film industry.

Anyway, great to see these films getting their due attention, especially Street Corner, (arguably) Muriel Box’s best film.

James – thank you for your comments. It was a fascinating project, working with Jo at BFI and hopefully we will find other opportunities to work together and look into the way government and the film industry ‘collaborated’. I must now go and get your book from our library!

This is a very interesting blog about the issues which concerned the Attlee government. There was an article in the Daily Telegraph of 1 February 2006 about Good Time Girl and the Hulten and Jones case, based on research when the Archives were released at the time, but it centred on the early appearance of Diana Dors as an actress in the film. That was scarcely relevant. When I wrote my recent biography of James Chuter Ede, that was almost all there was to go on. It is remarkable how as Home Secretary he had to deal with issues like this while he was putting through some very far-reaching legislation. Treatment of young offenders was one of his main concerns, with his background in education and as a JP. The further detail here adds to the picture, so my thanks for that.

But I still wonder how the family of a girl who was lucky to have escaped hanging felt they were in a position to complain about her treatment (if such it was) in the film.

Stephen – thank you for your comments. I agree that Chuter Ede’s background in education must have played a role in how he felt about this issue. And I also agree that you’d think Elizabeth Jones’ family wouldn’t worry about connections being made between her and the film considering her position!