Book tickets for our event on Friday 12 October:

Book tickets for our event on Friday 12 October:

The medieval royal family: Piety and commemoration

Even by the standards of his time, Henry III was a tremendously religious man.

Medieval kings were expected to give generously to religious institutions and to observe various feast days and festivals. Even Henry III’s father, John – who had no great reputation for piety – founded the Cistercian Abbey at Beaulieu in Hampshire.

But Henry III was a cut above. Documents held here at The National Archives show the vast sums of money that Henry spent on religious devotions within his own court and household, and the huge sums expended on gifts to religious institutions, to individual churchmen, and in alms to the poor.

Inferring actual religious feeling from a person’s actions is fraught with difficulty (King John used to give extra alms to make up for failing to fast or for going hunting on holy days) but contemporary chroniclers also attest to Henry’s genuine piety and high moral standards; notably among medieval kings he had no extra-marital relationships.

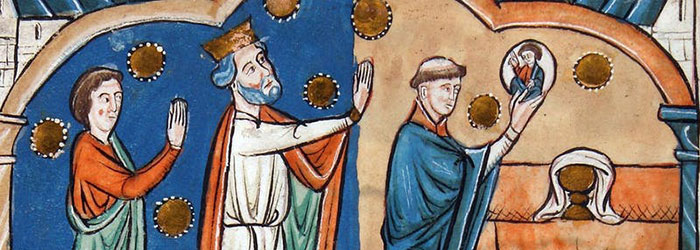

Illuminations of the miracles of St Edward the Confessor, from a 13th century abbreviation of Domesday Book (E36/284 f3v).

Although he venerated a number of saints, Henry III had a special devotion to St Edward the Confessor. Edward was one of the last Anglo-Saxon kings of England and had founded a new abbey at Westminster. Edward was actually too ill to attend the consecration ceremony in December 1065; he died soon after, to be buried in his new foundation. He was canonised in 1161 after a sustained campaign by the monks of Westminster Abbey – being the last resting place of a saint could be very lucrative, so it was very much in the Abbey’s interests to get their deceased patron canonised.

From William the Conqueror onwards, the Anglo-Norman kings had sought to emphasise their links with the pre-Conquest royal dynasty. Veneration of the Confessor fitted into this pattern. But Henry’s devotion to him went well beyond that of his predecessors. He seems to have felt that he and the Confessor had much in common (one can detect here the robust encouragement of the Westminster monks once again); perhaps he saw in Edward another pious, peaceable king who was buffeted on a sea of troubles.

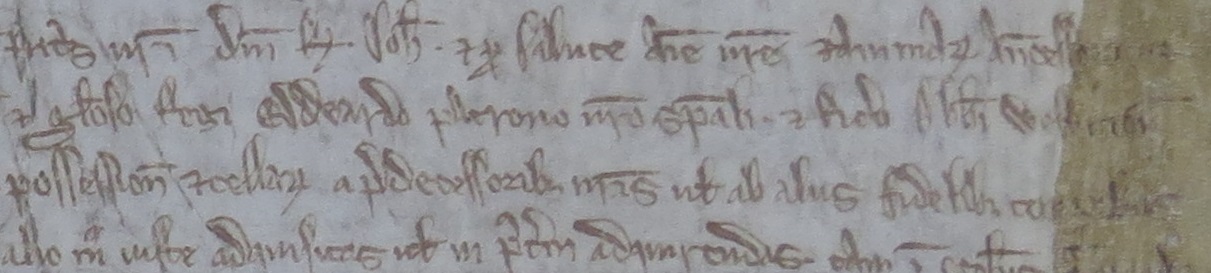

The reference in the Charter roll to Edward the Confessor as Henry III’s ‘special patron’ (C53/28).

His devotion offered many benefits to the Abbey. In 1235, Henry III conveyed a number of liberties to Westminster Abbey, recorded in a charter in which Edward the Confessor is described as his ‘special patron’.[ref]C 53/28 m.6; the charter is translated in Calendar of Charter Rolls 1226-1257, pp.208-9, although this incorrectly renders it ‘spiritual patron’.[/ref] In the late 1230s, there were several gifts from the king for candles and tapers to burn around the shrine. After this his devotion gained pace: in 1239, Henry took the deeply symbolic step of naming his first-born son Edward, after his spiritual patron. (Since the Conquest, first born male children who were expected to succeed had all been named William or Henry.) In 1241 he decided to rebuild the Confessor’s shrine, and in 1245 to rebuild the Abbey itself: an enterprise that took many years and a great deal of money.

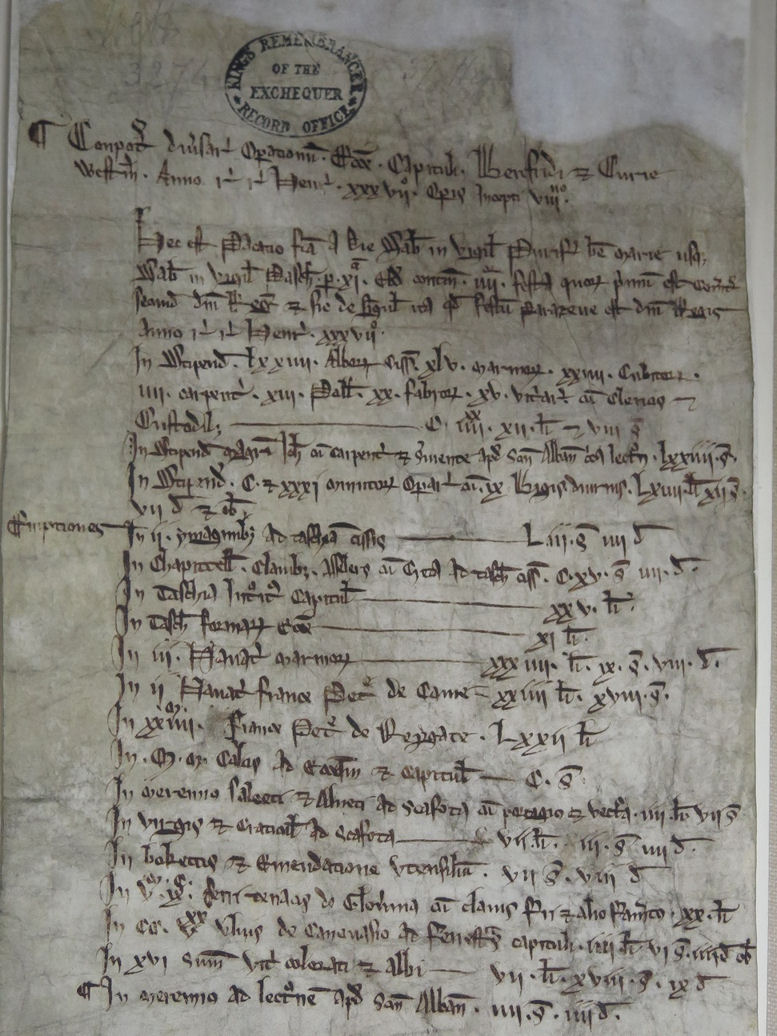

Accounts of the expenditure on the work survive here at The National Archives; although incomplete, they give us an idea of the enormity of the project. The total given for the fourth year of the work (1249) is £2,063 9s 1 ½. For the fifth year (1250), the total was £2601 5s 11 ½ d. Henry III, like many medieval kings, was chronically short of cash. His expendable income rarely exceeded around £40,000 annually and was frequently a great deal less. The works on the Abbey thus took up a considerable portion of his budget. [ref]For an analysis of Henry’s finances based on National Archives records, see R.Stacey, ‘Politics, Policy and Finance Under Henry III’ (Oxford, 1987), pp.201-236.[/ref]

The accounts mention payments for stone of various different types, timber, firewood, marble and glass. They mention wages for workmen, quarrymen, goldsmiths, carpenters, cutters, coopers, scaffolders, glaziers and polishers. They itemise details such as the work on the capitals in the cloister and the cutting of the vaulting ribs. The interior of the Abbey was richly and colourfully decorated, and payments are recorded to painters and for the paint itself – as well as for gold leaf. [ref]These accounts survive in various records in the series E 101; they have been brought together and translated in HM Colvin, ‘Building accounts of Henry III’, (Oxford, 1971) pp. 190-287, available in our library.[/ref]

Part of the account of works at Westminster Abbey from 1253 (E101/466/30).

Alongside the financial details, other records held here provide details of the logistics of the project, including the problems caused by Henry’s cash flow problems. In July 1250, the Close roll recorded an order from the king to two royal officials: they needed to obtain £200 ‘by loan or by any other means, as best they can’ to pay the men in charge of the building works for the work ‘so that the building is not held up for lack of money’.

A Close roll entry for March the following year referred to having ‘600 or 800 men’ working on the church, giving an idea of the scale of the work. However, progress was frequently slower than expected and in November 1252 Henry’s official in charge received the order ‘to have the new great bell hung, so that it can be rung on the eve of the blessed Edward, and he [the official] is not to leave London until he has done this’.[ref] These Close roll entries (from the series C 54) have also been reproduced in Colvin, ‘Building accounts’, see above.[/ref]

In June 1267 there are signs of near-disaster: Henry was forced by financial pressures to pawn many of the jewels that he had given to adorn the shrine – although his conscientious promise to restore the items has meant that an astonishing list of the jewels and their value survives on the back of the relevant Patent roll.[ref]C 66/85 m.19d; the full list is reproduced in the Calendar of the Patent Rolls 1266-1272, available at The National Archives.[/ref]

As well as his attention to the Abbey and shrine, Henry was also strict in his observance of the Confessor’s two feast days (commemorating Edward’s death on 5 January and his translation on 13 October). He spent large amounts of money on these observances. For the feast on 13 October 1268, 750 years ago, the Liberate rolls preserved at The National Archives include payments to Joce, the king’s buyer, of £60 for (unspecified) provisions for the feast; there are also payments to the sheriff of Wiltshire of £9 2s 6d for 146 muttons, and to the sheriff of Hampshire of 21s for the transport of 37 carcasses of beef. [ref]C 62/45 m.6; translated in the Calendar of Liberate Rolls 1267-72.[/ref] This expenditure would amount to tens of thousands of pounds in today’s money – and one can scarcely imagine a feast on such a great scale that 146 sheep died for it. And, in addition to the feasting, Henry would pay for the feeding of the poor in Westminster Palace.

The translation of the body of Edward to his new shrine before the high altar in the rebuilt church took place on 13 October 1269. Henry died just three years later, in November 1272. He was laid to rest near the Confessor’s shrine in Westminster, in the saint’s old coffin – although a few years later his son, Edward I, had a grand new tomb built for his father.

The tomb of Henry III at Westminster Abbey (Copyright DA Carpenter).

Westminster Abbey today is still very much Henry III’s building, although visitors today can also see the spectacular Lady Chapel – added by Henry VII in the 16th century – and the 18th century West Towers designed by Nicholas Hawksmoor. The magnificent shrine of St Edward, and the equally impressive tomb of Henry III, still have pride of place in the abbey which was so important to both of them.

On Friday 12 October, the eve of the Feast of the Translation of the St Edward the Confessor, we will be holding a special event at The National Archives on Henry III, St Edward and Westminster Abbey. There will be talks from three expert panellists and a display of some of the unique documents held here that illustrate the history of the abbey and of Henry’s devotion to the Confessor. These will include the fabulous 13th century Domesday Breviate (pictured above), which has illuminations of the miracles of St Edward the Confessor.

The money he gave was actually money from the ‘ordinary’ people of England and he certainly didn’t build Westminster Abbey himself (now that would be piety), he just gave money to rebuilding Westminster Abbey.

What was the total cost of the rebuilding?

Hello Laurence – that’s a good question, though one it is not possible to answer with complete accuracy. Not all of the records survive so any attempt to add up the totals is necessarily be incomplete. Colvin has published a lot of the surviving building accounts (see note 3) but I’m afraid I don’t currently have access to that book so I can’t check whether he attempts to calculate the exact cost of the abbey works. However, in his History of the King’s Works (HMSO, 1963), Colvin quotes a document in the archives of Westminster Abbey (not TNA) that states that in 1261 the grand total stood at £29,345 19s 8d. One can add to that Colvin’s estimate based on Pipe Roll evidence that in the last nine years of Henry’s reign expenditure totalled over £10,400. That would give a grand total of over £40,000 spent during Henry’s reign. (David Carpenter, in his new biography of Henry III, makes the point that this was enough to build four castles during the reign of Edward I.) The Abbey remained unfinished at the death of Henry III and work continued sporadically for another 150 years, costing (again, using Colvin’s estimates) another £25,000. Some of this was paid for by royalty (notably Richard II and Henry V) but most was raised by the monks themselves. If you are interested in finding out more about the works and Henry’s religious giving, I would recommend Colvin, History of the King’s Works, which has a chapter on the Abbey, and Carpenter, Henry III (Yale, 2020).

Excellent historical facts