On 16 March 1976 Harold Wilson caused a political sensation when he announced he was to resign, just over two years into his fourth stint as Prime Minister, and five days after his 60th birthday. He had been Labour leader for 13 years and Prime Minister for nearly eight years.

Harold Wilson at National Coal Board Gala, 1950 (catalogue reference: COAL 80/1119)

As Prime Minister leading two Labour administrations between 1964 and 1970, Wilson was keen to bring about a modernisation of Britain’s economy and society. Under his leadership, the Labour governments introduced liberal social policies, including the abolition of capital punishment and the decriminalisation of homosexual acts in private between two men, and changed abortion law. Wilson returned as Prime Minister following the February 1974 election, forming a minority government, and then called another election in October 1974 at which he secured a majority of three. He achieved further social reforms during 1974-76 but had to wrestle with the problem of soaring inflation. It has been said by some that Wilson’s greatest achievement as Prime Minister was keeping British troops out of Vietnam.

Wilson’s resignation was unusual because, for most of his party and the general public, the announcement came ‘from out of the blue’, and was not (seemingly) prompted by any obvious health issues; Harold Macmillan had been the last prime minister to resign while in office, in October 1963, on the grounds of illness.

The unexpected nature of Wilson’s departure gave rise to various conspiracy theories, and a suspicion in some quarters that Wilson’s resignation was forced, for some secret reason. This blog post to mark the 40th anniversary of this event is not concerned with such theories – as always, our approach is to highlight the story as told through the public records.

Wilson announced his decision to Cabinet on the morning of 16 March 1976. In his Personal Minute to all members of the Cabinet (which can be seen in PREM 16/1072) he revealed that he had taken the decision to resign in March 1974. He stated:

‘I have not wavered in this decision and it is irrevocable’.

Following on his long career in Parliament and at the centre of government, ‘no one should ask for more’. He added that he was resigning to allow others from ‘the most experienced and talented team in this century’ to be given the chance to seek election to the post of Labour leader. He cleared stated that there were no hidden issues behind his resignation.

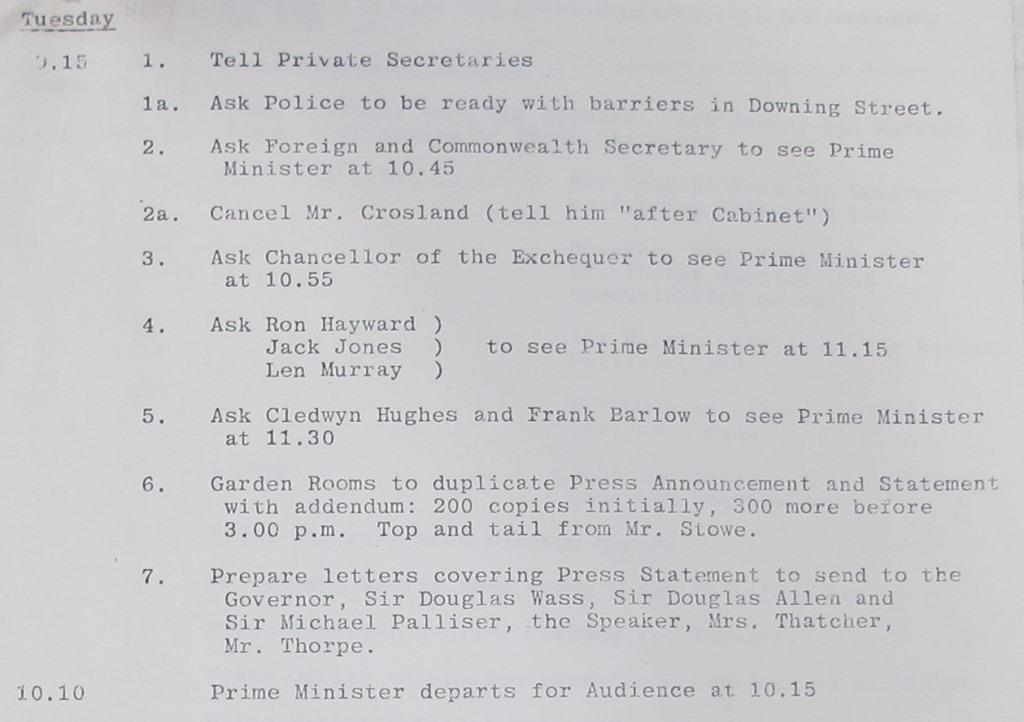

In his biography of Harold Wilson, Ben Pimlott describes Wilson as ‘ a man of numbers, timetables and calendars’.[ref] 1. ‘Harold Wilson’, Ben Pimlott, p.649 (HarperCollins, London, 1993).[/ref] It can be argued that this aspect is borne out by the ‘Action Plan and Timetable’ for 16 March which appears in PREM 16/1072. Joe Haines, Wilson’s Press Secretary, states that work on such a timetable began in the autumn of 1975.

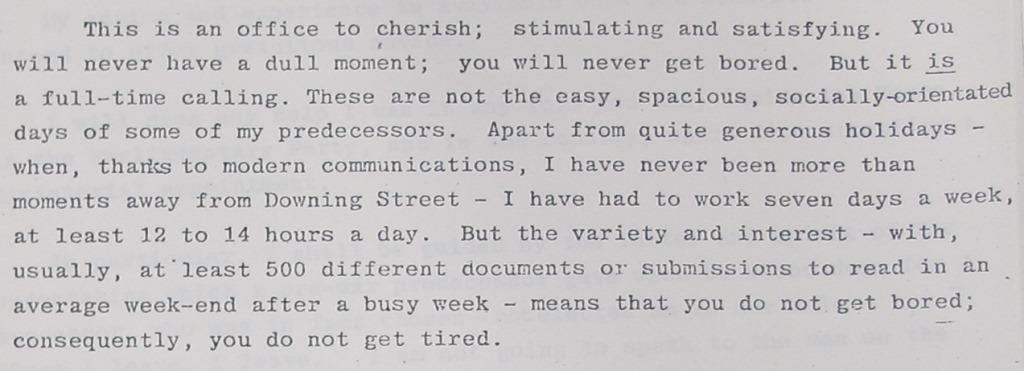

Referring again to the Prime Minister’s Personal Minute, in words addressed to his successor, ‘whoever he or she may be’, Wilson reflected on the challenges of being Prime Minister, and the level of commitment involved, while accentuating the positive aspects of this:

‘Apart from quite generous holidays… I have had to work seven days a week, at least 12 to 14 hours a day. But variety and interest… means you do not get bored; consequently, you do not get tired.’

Extract from the Prime Minister’s Personal Minute, 16 March 1976 (catalogue reference: PREM 16/1072)

Looking forward to the next Prime Minister’s administration, Wilson ended on a consensual note, expressing his wish that ‘all concerned will comply with the spirit of the Speaker’s Petition to the Queen on behalf of the Commons when a new Parliament meets: “that the most favourable construction may be placed on all your proceedings”.’

James Callaghan won the contest for the Labour leadership and became Prime Minister on 5 April 1976.

Of course there were quite a lot of downs in Wilson’s time, not least the decision to devalue Sterling whilst people were away on holiday abroad in 1967 and the issues with the Trade Unions over strikes, and not forgetting his going against his Cabinet colleagues and deciding to renew Polaris. Wilson it is said had alleged views on ‘reds under the beds’. On the plus side Wilson’s Governments were not like MacMillan’s Government who had at least one relative in his Cabinet and who were so removed from working people, at least Wilson had women in his Cabinet. Wilson’s opposition to taking part in the war against Vietnam was a major win by Wilson for the UK. I would dispute the claim that he changed the Abortion law, it was actually David Steel of the Liberal Party whose Private Member’s Bill which became the Abortion Act 1967 after it was decided to support it, not a very usual event. Wilson was a Prime Minister that was ‘into’ new technologies, although not adverse to having his photo taken with The Beatles and a lack of ‘spin doctors’ to a great degree.

Whilst a Conservative voter all my life I did respect Harold Wilson as a firm leader of the Labour Party. I may be wrong but I always felt he was honest, unlike some of those who came after him. However, in my view his government were responsible for unaffordable wage rises in the seventies which led to the decline of the UK manufacturing and coal industries. These rises priced us out of world marketplaces and ultimately brought high unemployment to the North and Midlands.

Whether ‘unaffordable’ wage rises ‘lead to the decline of UK manufacturing and coal industries’ is highly debatable, given the relative proportion of labour costs in the total cost of manufacture and production. Far more serious long term decline is likely to be caused by lack of investment, both private and public, as any economist will tell you.

Re. Wilson, his greatest achievements lay, I think, abroad. Firstly, the negative but crucial achievement of keeping us out of the Vietnam War; although at the time he was vilified for ‘supporting’ the Americans. He trod a tightrope placating them, rather. Second, the divesting of the remainder of the British Empire. Third, his handling of the run-up to the first referendum on the EC in 1976.

In the long term, the social reforms in terms of Sexual Equality, Race Relations Act have had far more effect on the societal norms of this country than anything before or since. Add in the private members bills (Sexual Offences Act, Abortion) which the Wilson government in the shape of Jenkins enabled, and you have the tipping point, the moment when ‘equality’ became the expectation, and prejudice and discrimination became generally socially unacceptable.

What did it mean that Harold Wilson’s resignation was compared to the watergate scandals

Harold Wilson paved the way for the OpenUniversity which offered learning opportunity at home for so many not just the few.