Last year, when I finally took the plunge and sheared my precious dreadlocks (which I had grown rather attached to after over a decade of loving cultivation), I was confronted with a new situation – human hair is a commodity. I say this because everyone who learnt of my separation from my 10 year growth offered the same response – ‘Did you keep them? You could sell them you know.’

I never did sell my hair. Somehow it just never felt right (the sale, not the hair), but if I had, I would have been taking my first baby steps in an industry which stretches back at least 5000 years. The Ancient Egyptians constructed wigs out of human hair, amongst other things, and wore them as much to denote rank as for reasons of hygiene. The English word wig is derived from the 16th century French word for a head of false hair – perruque. The perruque became known colloquially as a periwig, and the peri was eventually dropped to leave simply wig by the later part of the seventeenth century.

Wigs were a big deal in the eighteenth century, as evidenced by the number of ‘periwig makers’ appearing in our catalogue. To have a large wig was a sign of affluence and to wear a wig was not a gender specific act. Having said this, women’s wigs of the time did tend to be larger and more elaborate than their male counterparts. These voluminous hairpieces required hair – lots of it – and the heads of rural working class people provided the main source. Perhaps there was not enough homegrown hair to meet the demand, for there is evidence that hair was also being imported from across the Channel (PC 1/3/84)

This letter was sent to the Privy Councillor (who at that time was William Coventry, the 5th Earl of Coventry) on 27 October 1720 by an unknown Londoner who simply signed the document ‘A.B’.

Letter signed A.B. about the import from France of human hair infected with the plague. Catalogue reference: PC 1/3/84

Its very concerned author writes to advise the Council of the health risks surrounding the importation of human hair from France:

‘there is nothing so dangerous and infectious as this haire is for it may be cutt off from the heads of some who have perished under that great & lamentable infection…’

The ‘lamentable infection’ referred to is most likely the Great Plague of Marseille which killed 100,000 of Marseille’s citizens. Given that England had seen intermittent plague episodes since 1347, the largest of which being the infamous ‘Great Plague’ of 1665-66 (which claimed over 100,000 lives), you can’t blame A.B. for wanting to ‘prevent the mischeife that may attend the permitting [of] the same to be imported…’. Interestingly, the letter also suggests that French hair was rather a lucrative business, not least for the British Government who imposed high duties on its import.

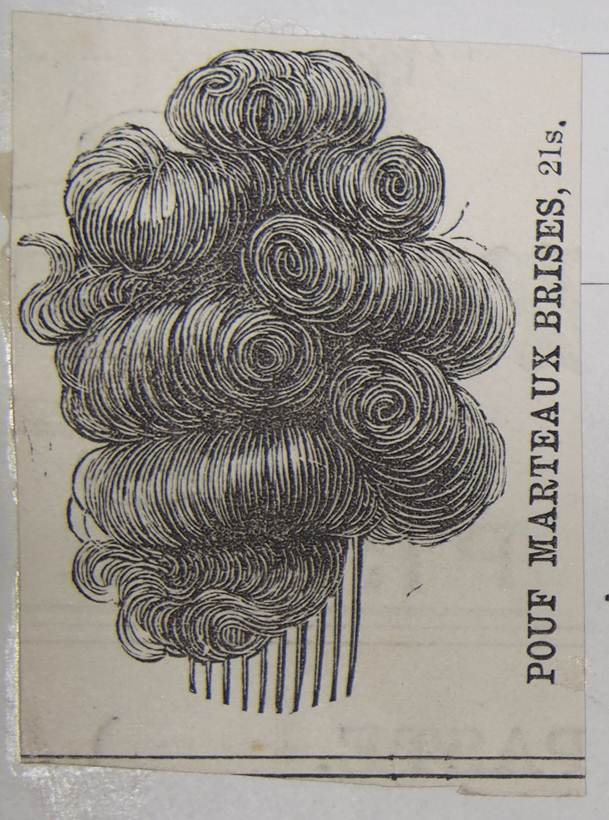

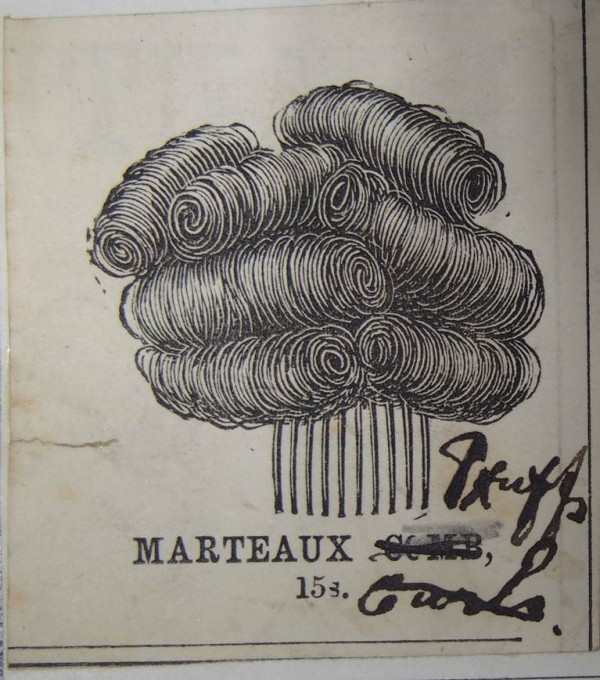

Moving forward in time, the elaborate styles characteristic of the Victorian and Edwardian eras called not for full wigs, but for the ingenious use of false sections of hair to alter the natural lines of the hair. These attractively named ‘New Zephyr Front’, ‘Marteaux Puff’ and ‘Pouf MarteauxBrises’ being excellent examples of such partial wig wizardry:

Photograph of artificial hair representing a lady’s fringe and named ‘New Zephyr Front’ (1890) . Catalogue reference: COPY 1/401/18

Photograph of artificial hair on comb called ‘Pouf Marteaux Brises (1890). Catalogue reference: COPY 1/401/19

Photograph of artificial hair on a comb and called Marteaux Puffs (1890). Catalogue reference: COPY 1/401/20

And this is a flavour of the elegant coiffure one could achieve with such methods:

Photograph of female head wearing the ‘Grecque Coiffure’ Front view (1890). Catalogue reference: COPY 1/401/21

Sadly for those whose bread and butter relied on the sale of other peoples’ hair, the false hair industry, at least in European contexts, tailed off until the 1960s, where the rapidly alternating trends in coiffure ushered in a veritable wig renaissance. A period to which this slightly comical Pathe newsreel provides testimony.

In the lead up to the swinging sixties, Britain’s first celebrity hairdresser, Raymond Bessone (aka Teasie Weasie), was at the top of his game – in spite of a public slight on the Duchess of Windsor’s hairstyle of choice. My next post takes a look at some traces I have found in the archives, relating both to his fascinating life story, and that of his protégé and fellow celeb stylist Vidal Sassoon.

Hi Etienne,

Great blog, particularly loving the exotic names for the haripieces.

I was reminded of this blog when I was looking through CUST 5/1B, the customs ledger giving the quantities, prieces and duty levied on ‘imports under articles’ for 1800.

One of the commodities detailed is ‘Hair, Human’! It seems that in 1800 3434 lb of human hair was imported into England, coming from Germany and France.

This was worth £1144 13s 4d altogether, and had a rather hefty duty of £377 14s 10d levied on it.

There are CUST 5 ledgers throughout the 19th century so it would be interesting to follow the fluxuations in demand for wigs through the period.

Thanks again for a fascinating blog.