The first Bonfire Night celebration happened on the very evening of the discovery of Gunpowder Plot – 5 November 1605. On Thursday 7 November John Chamberlain reported to his friend, the diplomat Dudley Carleton: ‘On Tuesday at night we had great ringing and as great store of bonfires as I think was ever seen’.

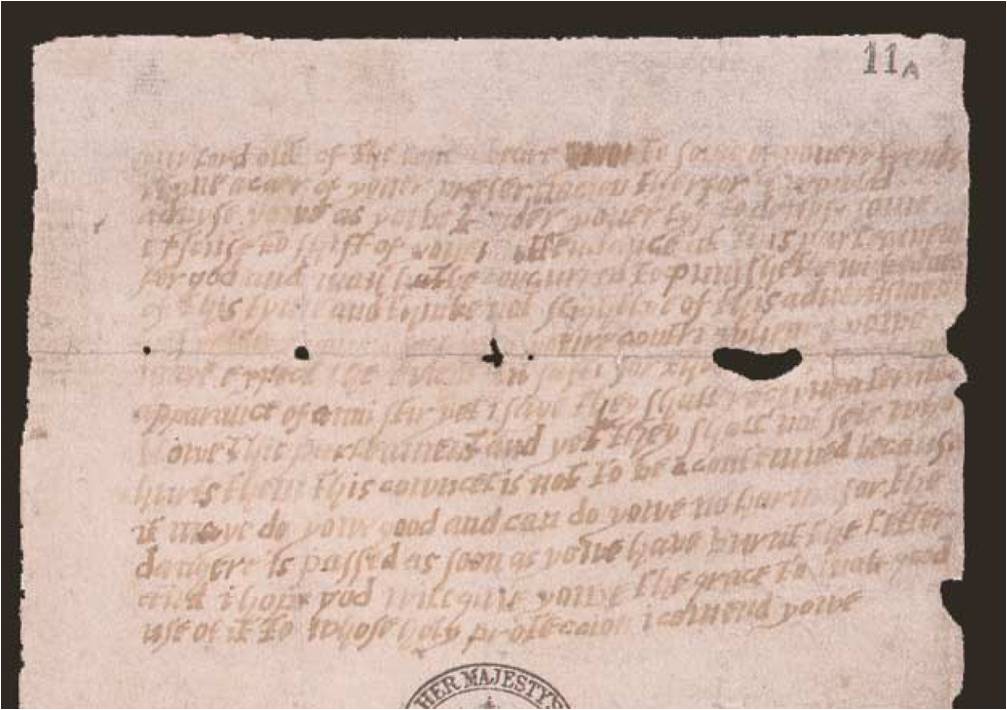

This letter (SP 14/16/23), along with many of the key documents of the plot, can be found in the State Papers at The National Archives. Some, like the confession of Guy Fawkes of 9 November 1605 with its faint signature (SP 14/216/54), can be viewed in our image library. The relevant volumes of State Papers are available online in calendar form on the Institute of Historical Research‘s website.

Who was really responsible?

Dudley Carleton had helped Thomas Percy rent his vault beneath the parliament house, and therefore allowed Guy Fawkes, posing as Percy’s servant, the perfect venue to lay the gunpowder. This earliest report of the celebrations was made to a man who had reason to fear as well as celebrate the discovery. This ambiguity has hung on the celebrations ever since: who is celebrating what and why, and who was really responsible?

Parliament’s website is understandably very strong on the documents and ceremonies associated with the preservation of Parliament. Plenty of other people since 1605, including the poet John Donne giving the annual sermon of thanksgiving on ‘Gunpowder Day’ 1622, have been rather more excited by the prospect of the explosion than its prevention. Perhaps it is these ambiguities and unanswered questions which make the story so attractive for teaching, and The National Archives’ Education service has teaching resources which encourage children to supply their own answers based on the evidence.

The Gunpowder Plot remains a plot of gentlemen who found noblemen occasionally useful to them, but showed little compunction about blowing them up in The House of Lords. Dudley Carleton had also acted as secretary to the Earl of Northumberland who was the authorities’ prime suspect as the ‘great man’ behind the plot. The Earl spent 16 years in prison himself – in some comfort, as became his rank – in the Tower of London. Sir Edward Coke, the attorney general, suspected Sir Walter Raleigh, though Raleigh was already in the Tower while the plot was hatched. Others suspect the Earl of Salisbury of making the whole thing up, but no convincing link to a great man has been sustained. Only when, in financial desperation, Robert Catesby recruited some really rich landowners were they betrayed by the famous anonymous attempt to warn Lord Monteagle.

‘Divine agency’?

The government liked to say that the warning given to Lord Monteagle was a matter of divine agency, but his brother-in-law Francis Tresham was a more likely candidate. The letter, like so much of the material diligently compiled during the investigation, tended to challenge the public official view of events. Monteagle himself was implicated in plans for a Spanish invasion before the death of Queen Elizabeth and was reported as saying King James was ‘odious to all sorts’.

Perhaps, however you feel about the preservation of parliament itself, the preservation by the government of so much fascinating evidence, much of it embarrassing to it, is sufficient reason for celebration.

It is of concern that you can’t find a reference in Discovery to Fawkes or the Plot letters in SP 14/16, whilst it shows that you don’t need Operational Selection Policies to preserve the important papers, the archivists of the 19th century knew what needed to be preserved. There is of course a proviso in the Public Records Act 1958 that all records before 1660 must be kept. The reason why Fawkes’ signature is faint is that he was tortured.

I agree Northumberland is suspect as ring leader, the greatest isn’t he