The Great Fire, which was finally extinguished 350 years ago today, not only destroyed the homes and livelihoods of thousands of people but also was a significant threat to the government of the country, destroying law courts and sources of taxation and risking the defensive symbol of the nation itself, the Tower of London.

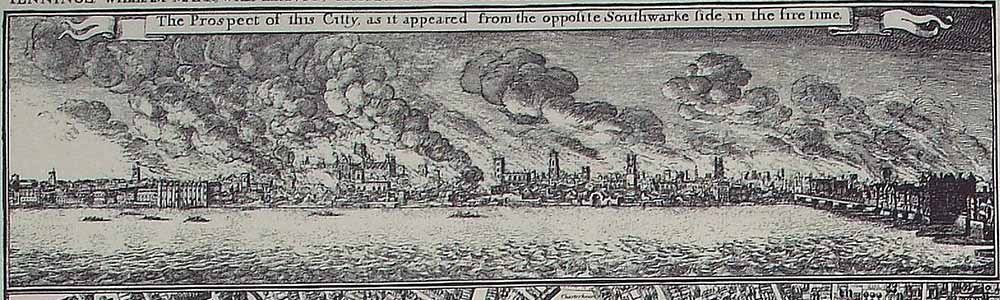

Section of Hollar’s Survey of London showing the City in flames (catalogue reference: ZMAP 4/18)

Together with a dedicated group of volunteers, I am currently cataloguing entries from the registers of the Privy Council (PC 2) for the 1630s.[ref]1. Entries will be added to Discovery in 2017.[/ref] The Council managed the business of government on behalf of the king. Its registers record drafts of letters, proclamations and warrants issued to ensure the smooth running of the kingdom. They have been published as full transcripts in the Acts of the Privy Council series up until 1631, but the only way currently to search the subsequent registers is through indexes at the end of each volume or by browsing by date.

Having become aware of the vast array of business passing before the Council, I took a look at the register for 1666 to see how the Privy Council responded to the critical emergency of the Great Fire in its immediate aftermath. Was it a 17th century COBRA meeting, managing every element of the response to the crisis, or did the real management happen elsewhere? Was the primary response humanitarian or materialistic?

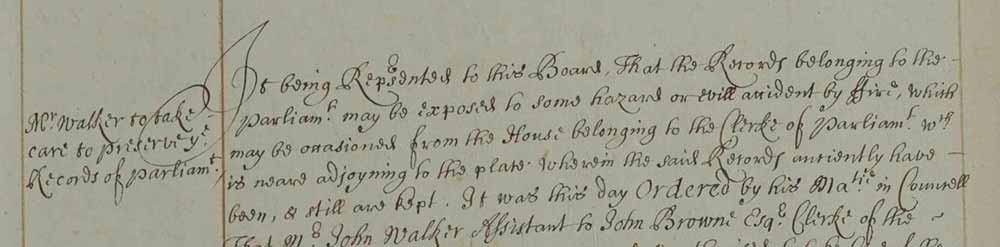

On 5 September, the Privy Council, with the King present, met for the first time since the outbreak three days before. Somewhat bizarrely, their first concern did not relate to the City of London at all, let alone its inhabitants. Instead, they were concerned to protect the records of Parliament from the risk of fire, despite the fact they were over a mile away from the blaze. They ordered that the house of the Clerk of Parliament, which adjoined where the records were kept, should be pulled down in the case of imminent danger from fire and the windows closed up with earth.

‘to take care to preserve the records of Parliament’ (catalogue reference: PC 2/59, f.78)

The archivist in me finds this focus on the safety of the records rather pleasing, but it is nevertheless a little shocking that this was the Council’s first order of business in the face of the disaster still threatening Londoners.

The Council met again the next day and turned its attention to some of the people affected, ordering that the charitable hospitals and companies destroyed by ‘the suddain & lamentable accident of this violent Fire’ should ensure that their almspeople and pensioners ‘now exposed to the saddest Condicion immaginable & in danger to perish with hunger and Cold’ were provided with food and accommodation.

The Council’s next concern was eminently practical. The water engines, buckets and fire hooks owned by the City had been left scattered around, so it ordered that they should be gathered together and repaired and that the roadway over London Bridge should be cleared to allow for the delivery of provisions to the City.

The fear that the fire could reignite and threaten the rest of London and Westminster was very real – no doubt there were areas still smouldering. The Deputy Lieutenants and Justice of the Peace were therefore required to supply 200 able-bodied men together with tools and food at Temple Bar at 17:00, ready to prevent ‘the further fury of the rageing Element’. The Victualler of the Royal Navy was required to provide biscuits, butter and cheese to the men still working on fully extinguishing the fire. The order includes details of the areas which were still at risk, all to the west of the City – from Temple Bar via the Rolls Garden to Holborn Bridge.

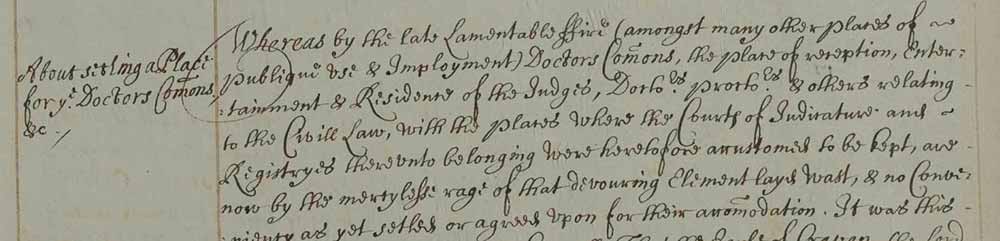

Unsurprisingly, attention was next given to a major source of royal revenue. The Customs House having been burned down, an alternative venue for the payment of this taxation had to be identified. It took another 20 days for the Council to exhibit the same concern about the law courts at Doctors’ Commons, perhaps because the Michaelmas law term was not due to start until October.

Order that a new home for Doctors’ Commons (‘by the mercylesse rage of that devouring Element layd wast’) be identified (catalogue reference: PC 2/59, f.89r)

The Lord Mayor was urged to concentrate on relieving the poor and on working out how to take them ‘out of the open Fields into such Covert & shelter, as the Suburbs & the remayning part of the City will afford, so to prevent their utter ruine & destruction’. A common theme throughout all these orders is that existing systems of poor relief were to be used; there was no further contribution from the king’s revenues. Churchwardens and other parish officers were urged to take care of those lying in the fields, particularly women about to give birth and the sick, using vacant houses to accommodate them, then inns and places of public entertainment and, once those were full, resorting to private houses. Those able to pay for their lodgings would be required to do so.

The Privy Council turned its attention to reducing the risk posed by any subsequent fire. Those people living next to the Tower of London, who were probably breathing a sigh of relief at having avoided destruction by fire, must have been dismayed to learn of the Council order to demolish their houses in order to protect the Tower. Affected inhabitants successfully petitioned for time to remove their houses and goods.

On 10 September, a proclamation was ordered for a day of humiliation during which collections would be made for the poor. Having overcome the immediate danger of the fire itself, minds were now turning to the need to appease an apparently wrathful God. The Council also expressed an understandable concern over the amount of gunpowder held in private hands, ordering any within ten miles of the City or the King’s ship yards to be brought into royal stores for safekeeping.

The final entry relating to the fire made in the register during September 1666 gives an indication of the losses suffered by some individuals. Captain John Wadlow stated he had lost 100 tunns (casks) of Spanish and French wines as well as his greatly valuable household goods. He appears to have been unable to empty his house in the face of the oncoming flames as it was requisitioned by the Duke of York and Privy Councillors and the streets around were blocked with timber. Although he pointed out that he had paid significant amounts in customs, including one payment of £1,000 that year, he did not ask for compensation, but merely permission to import further casks of wine which he held in Flanders.

The aftermath of the fire continued to feature regularly in the Council’s business for many months, and indeed years, as plans to rebuild the City took shape.

For further examples of sources in the archives for the history of the Great Fire, see our education resources.

Utterly fascinating ~ And, of the snippets of beautifully quilled text of the ‘Council’ of the Great Fire of 1666’s time shown is intriguing for the columned design of the (parchment) sheet written upon being a formal ‘ledger’ isn’t it? We have to sing to high Heaven for the acidulous record keeping ~ otherwise, what would we know of the great conflagration of London? For the Council to be concerned for the written records before consideration of any other factor where the devastating conflagration has wrought havoc and homelessness to people and property seems quintessentially and prosaically and poetically, if inhumanely, English. Haven’t we seen this of late with Afghanistan’s stray and unwanted dogs and cats deemed worthy of safety and saving above desperate escaping of ‘today’s conflagration of 2021? Thank you 🙂