Christmas Day 1914 was the day of the Cuxhaven Raid, when the British Royal Navy deployed aircraft carriers for the very first time. It was also the first time that air and sea power had combined to attack targets on land, and it was the day on which my Grandfather, James William Bell, earned the Distinguished Service Medal (DSM) for his part in the attack.

The sinister shadow of the Zeppelin airships, their large payloads, machine guns and ability to reach the English coast, had been looming large in British minds, and previous raids had been carried out on airship sheds at Düsseldorf, Cologne and the works at Friedrichshafen. But the coming raid would be different.

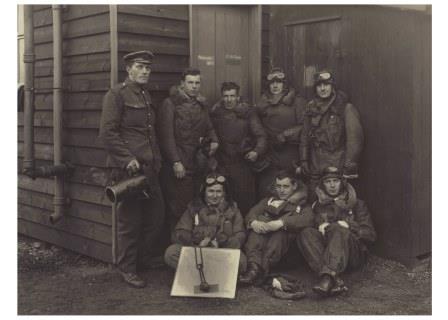

CPO James WIlliam Bell (seated with map).

‘Plan Y’ as the raid was officially known, would involve using nine Royal Naval Air Service seaplanes to find and bomb the German airship shed near Cuxhaven, in northern Germany. The seaplanes would be carried close to the German coast by three converted ferries: Engadine, Riviera and Empress. The planes would then be hoisted out by crane onto the sea, start their engines, take off from the water, find the Zeppelin sheds, drop their bombs, turn back, and land on the sea ready to be picked up by the surface vessels. What could go wrong?

On Christmas Eve, as chief mechanic on the Empress, my grandfather had been given 16 bombs, each weighing 20lbs, and told to drill holes in them so that they could be slung under the seaplanes in preparation for the following day’s operation. He was 21 years old at the time, and the rest of the crew were told to move aft in case Bell blew them all to pieces. Luckily he didn’t.

That evening 34 ships, including destroyers, cruisers, submarines and the three carriers moved out from Harwich, and from Scottish waters the Grand Fleet moved south to rendezvous in the North Sea, all to provide support and protection for the three vulnerable aircraft carriers. Bell was on board the Empress, ready to act as observer on aircraft number 814, an Admiralty Type 74 seaplane, with Flight Sub-Lt Vivian Gaskell Blackburn as his pilot.

Apart from the three bombs allocated to each plane the only weapons on the aircraft were the pilot’s revolvers, with six packets of ammunition. Bell was also allowed to carry a rifle.

Travelling through the night, the ships reached the seaplane launching point at 6am on Christmas morning. By 6.30 all nine planes were in the water, although the engines of two planes refused to start so they were hoisted back on-board. The remaining seven planes flew off into a misty sky, reaching the German coast an hour later.

On their way they drew gunfire from enemy ships, and over land the fog became thicker, forcing the pilots to fly low as each tried to spot landmarks along the way. The fog was so bad that Gaskell Blackburn was unable to tell when he crossed the coast line. He spotted a railway line, flew south, then north, with intermittent anti-aircraft fire bursting around them. With no sign of the airship sheds, and realizing that fuel was getting low they decided to head back. They came to Wilhelmshaven where one of the floats on their plane was ripped apart by a small calibre shell, and Gaskell Blackburn dropped two of his bombs over the land battery responsible. On reaching the coast they headed north looking for the carriers.

Bell’s First World War Medals.

In the meantime the Empress had come under attack from two German Friedrichshafen seaplanes and the airship L6. Several bombs were dropped near the ship, and the crew fought back with rifle fire. Other ships rallied round in support, and the airship withdrew into the clouds.

Gaskell Blackburn and Bell landed their plane 25 miles away, near the Royal Navy submarine E11, captained by Lt. Cmdr. Martin Nasmith. The submarine was already towing another of the British seaplanes, No. 120, which had come down unable to find the carriers. As my grandfather’s plane hit the water the damaged float collapsed, and the plane tipped up with its tail in the air. Shortly after this they were joined by seaplane 815 which was also running out of fuel. Another airship, the L5, was now approaching the submarine, but Nasmith manoeuvred the sub close enough to No. 815 that the pilot and observer were able to step aboard. Gaskell Blackburn and Bell were further out, however, and had to dive into the sea and try to swim to the E11. Nasmith shot the seaplane’s floats with a machine gun to prevent the aircraft coming into enemy hands.

Gaskell Blackburn reached the E11 first, as Bell struggled in the swirl created by the submarine itself. As the enemy airship closed in a leading seaman jumped down from the conning tower, waded along the gun-platform and threw my grandfather a line. Grabbing the rope he was hauled on board and was bundled down the hatchway as the E11 submerged. He felt a slight bump as the sub reached the seabed, before an appalling crash reverberated through the hull when the first of two bombs from the airship burst in the water above them. No damage was done, and apparently the crew had Christmas dinner on the seabed before heading back to Harwich Harbour.

The raid had not been a success in terms of achieving its target, since none of the seven aircraft was able to find the Zeppelin shed, but it was a milestone in the development of aircraft-carrier based operations. It also provided useful reconnaissance reports, and tested the German reaction to an attack on home turf.

Bell was awarded the DSM for his exploits. Flight Sub-Lieutenant Gaskell Blackburn ended his official report on the attack, which is held at The National Archives under reference ADM 186/567, with the words: ‘The observer, CPO Mechanic Bell’s behaviour was magnificent throughout’.

Here at The National Archives we hold two documents concerning the actual raid: ADM 186/567 – Seaplane operations Against Cuxhaven 25 Dec 1914: report, and AIR 1/2099/207/23/4 – Report on seaplane operations against Cuxhaven. For further reading there are at least two published books on the subject: The Cuxhaven Raid by R D Layman, and The Zeppelin Base Raids, Germany 1914 by Ian Castle.

Hi,

My grandfather was also involved in the Cuxhaven Raid. He was a seaplane pilot and I have several photos of him and other officers on board HMS Riviera, including Flt Cdr Kilmer and Flt Lt Edmonds who were awarded the DSO. Other officers named in photos are Hartlett, Courtney, Laidlaw, Punnett, Limpus, Jefferies, Holmes, Etherington, Markham, Cobb, and my grandfather, Albert Durston.

I’ve only researched this recently so it’s really interesting to read your blog. Thank you.

My grandfather, Captain George Thomas Blaxland, had been master of the Empress before the War, when it was a merchant ship. He acted as Pilot for the Cuxhaven raid under the command of Sir Freddie Bowhill, for whom he had considerable respect and admiration. I researched my grandfather’s history some years ago but have only now seen this blog. I have a photo of the Empress under attack. I also have a menu for a commemoration dinner on 15th January 1921 held at the Savoy Hotel in London. It has been signed by officers who were present.

Thank you all for the information that you have shared.

Here is a link to the photograph of the Empress under attack.

https://www.hobyanddistricthistory.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/Zeppelin-bomb-and-Empress-2.jpg