The hugely successful and widely praised TV series Gentleman Jack is a period drama set around the turn of the 18th to the 19th century, but is not one that follows the usual pattern of courtship and dashing romance. Instead, this series focuses on the life of a woman, Anne Lister, and her many relationships and sexual exploits with other women. Not normally something you would associate with the era of Jane Austen and the Brontës, nor your typical Sunday night viewing…

Portrait of Anne Lister (1791-1840), by Joshua Horner, c.1830

What makes the series all the more fascinating is its basis in fact. Lister’s extraordinary diaries have given historians huge insight into lesbian relationships in the past. Lister left an estimated five million words[ref]https://wyascatablogue.wordpress.com/exhibitions/anne-lister/anne-lister-the-journals/[/ref] documenting her life over many decades, including significant sections written in her own personal code. These extensive diaries record everything, from the routines of her daily life to her numerous sexual encounters with the ‘fairer sex’. The diaries and the scholarship around them have been used to inform this dramatisation of Anne’s life.

The 27 volumes and associated letters are held at the Calderdale Office of the West Yorkshire Archive Service. Lister’s diaries are a rare archival exception. Not only do they reveal Anne’s sexual identity, they also shed light on the lives of minor aristocratic women of the era and their involvement in politics, finances and travel. As well as the sections in code, Anne used an “X” alongside her text to denote a sexual encounter or orgasm[ref]Anne Lister of Shibden Hall, Halifax (1791-1840): Her Diaries and the Historians, Jill Liddington, History Workshop, No. 35 (Spring, 1993), pp. 45-77[/ref].

In this post I will be exploring records held at The National Archives, and what they can tell us about the life of Anne Lister and her lover Ann Walker. I’ll focus on the end of Anne’s life – and so what follows may contain series spoilers.

Anne’s earlier life

Anne was born in Halifax, Yorkshire, on 3 April 1791. At the age of 15 she began writing her diaries; even from this young age they detailed her explorations of her sexuality and relationships with women.

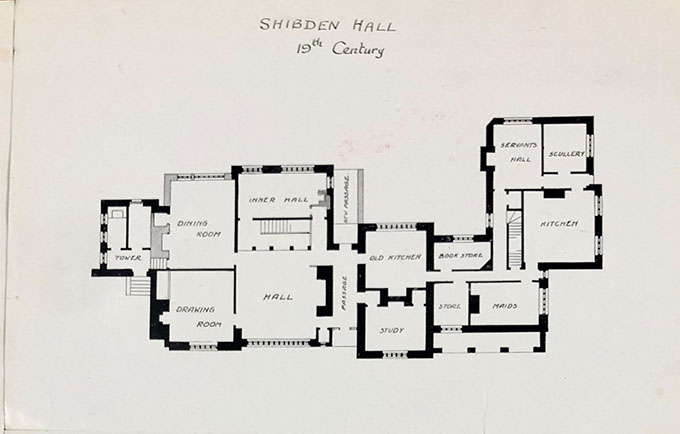

Image of Shibden Hall from Wikicommons and floor plan of 19th-century hall, The National Archives, WORK 14/846

In 1815 she went to live permanently with her uncle and aunt at Shibden Hall, where increasingly she took on a role in managing the estate. Lister was clever and a savvy business woman; she worked hard to improve the building and look after the property, although she often struggled to finance this.

In 1815 she went to live permanently with her uncle and aunt at Shibden Hall, where increasingly she took on a role in managing the estate. Lister was clever and a savvy business woman; she worked hard to improve the building and look after the property, although she often struggled to finance this.

Throughout this period she continued to have relationships with various local women.

In 1834, after several relationships and some devastating disappointments, Anne met the much younger Ann Walker. Walker’s wealth and social standing appealed to Lister, and they quickly formed a relationship. Just several months later Lister had persuaded Ann to join her living at Shibden Hall. Their courtship was not a smooth journey, with Ann unsure about commitment, and it took some time for the relationship to be solidified. Arguably their social standing protected them – how far was this kind of life available to lesbian women of other social classes?

I love and only love the fairer sex[ref]Monday 29 January 1821 [Halifax], I Know My Own Heart: The Diaries of Anne Lister, 1791-1840 by Anne Lister, p.145[/ref]

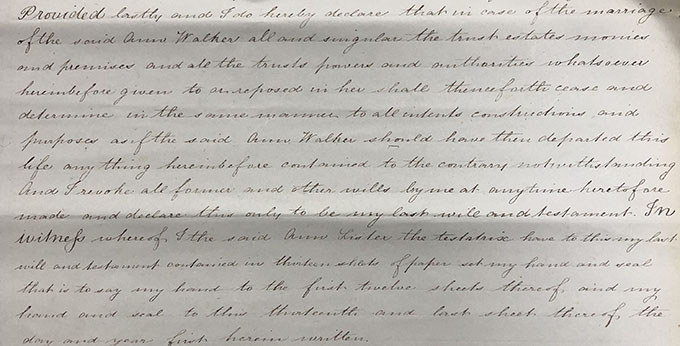

The National Archives holds a substantial collection of wills, including some bundles of originals in the series PROB 10. These are generally signed and sealed by the testators and witnesses. In these records we can find traces of the lovers’ relationship. Lister bequeathed her substantial estate to her ‘friend’ Ann Walker, but in an intriguing twist, stated that if Ann should marry she would be disinherited; ‘… as if the said Ann Walker should have then departed this life’. Either marriage or death would end Ann’s lifetime inheritance of Shibden (PROB 10/6000). Many of Anne’s former lovers had married – whether due to bisexuality, or as a means of getting by in a hetero-normative and patriarchal society that did not accept lesbian relationships. Anne was clearly worried about a similar thing happening to Ann Walker, after her death.

Extract from the will of Anne Lister, which highlights the conditions on which Ann Walker will have her lifetime inheritance revoked. The National Archives, PROB 10/6000

In return, Ann Walker was pressured to include Lister in her will, which is also held at The National Archives.

The will of Anne Lister. Wills proved during April 1841, surnames H-L. 1841 Apr. The National Archives, PROB 10/6000

In an era far before same sex marriage was made legal, the couple’s options to show each other their mutual dedication and love were limited. This exchange in their wills seems to be a way of legally solidifying their relationship. However, Lister and Walker also did something more personal to show their commitment. On Easter Sunday 1834 in Holy Trinity Church, Goodramgate, they took communion together – an act they both deemed as constituting their marriage. Two hundred years on, the church now bears a plaque acknowledging this as the location of the first lesbian wedding[ref]www.bbc.co.uk/news/amp/uk-england-york-noth-yorkshire-44938819[/ref].

Photograph of the interior of Holy Trinity Church, Goodramgate, 1908, where Lister and Walker’s marriage ceremony took place decades previously. The National Archives, COPY 1/523/184.

The couple took to travelling together, including a trip through Russia and Persia. Anne was an ambitious mountaineer and loved to escape the small world of Halifax. Walker’s wealth gave them the freedom to travel and explore.

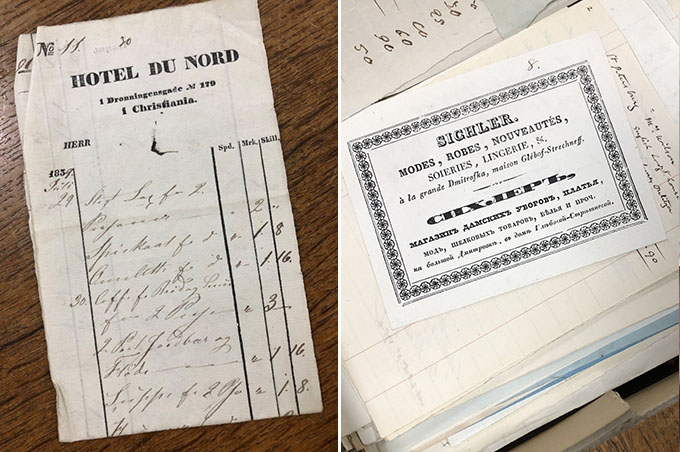

Tragically Lister died from fever while travelling in Georgia on 22 September 1840. Ann took the perilous journey back across the continents – a feat which, in the 1800s, took seven months, with Lister’s embalmed body in tow[ref]I Know My Own Heart: The Diaries of Anne Lister, 1791-1840 by Anne Lister, p.365[/ref]. Remnants of Lister’s travel experiences can be found in litigation files after her death. Items that survive include tickets and receipts for hotel and other expenses in Scandinavia and Russia, and a map of Finland (C 106/60).

Who was going to pay for the remaining expenses seems to have been contentious among Ann and the Lister family, resulting in a chancery dispute. Records such as these were submitted to the court as potential evidence; some items, such as account and notebooks, seemingly written in Anne’s own hand.

WALKER v GRAY Exchequer and Chancery: Master Richards’ Exhibits. The National Archives, C 106/60

The Commissions and Inquisitions of Lunacy

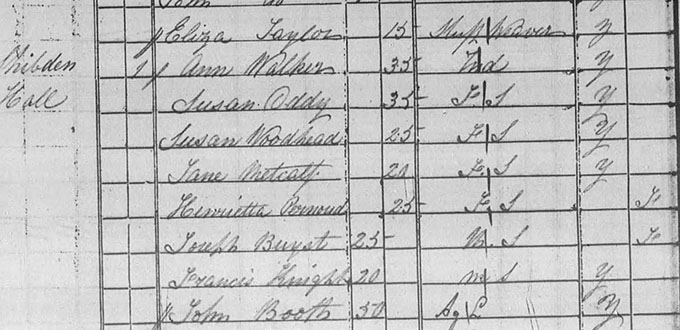

As requested in Lister’s will, Ann returned to Shibden Hall, but this time without her lover. The 1841 census shows the Shibden household shortly afterwards, and Ann is listed of ‘independent means’, alongside numerous servants.

1841 census, at Shibden Hall, Halifax. The National Archives, HO 107/1303/11

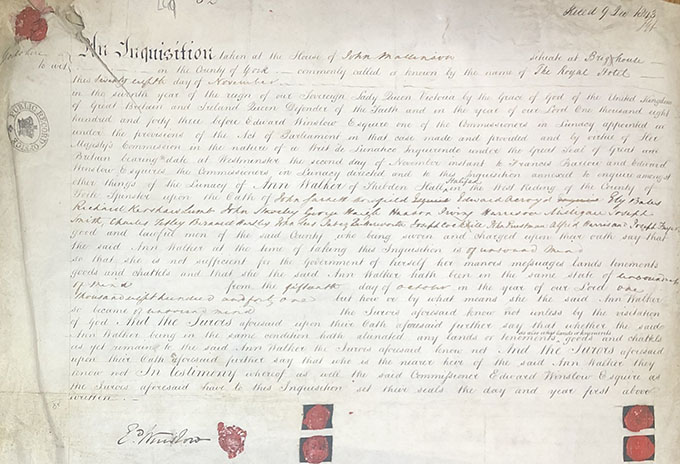

However, despite Lister’s careful planning, Ann was not to stay at Shibden Hall for long. Two years after Anne’s death, Ann was declared of ‘unsound mind’. She was removed from Shibden and her will, which survives, was deemed void. The Commissions and Inquisitions of Lunacy declared Ann insane (C 211/28/W249). The priority of this commission was the proper administration of the individual’s estate. Ann was sent to a York-based asylum and ended her days away from Shibden.

When Ann Walker died in 1855, Shibden Hall was inherited by John Lister. Despite their dedication and religious commitment to each other, she was not buried next to Anne Lister.

Ann Walker, spinster of Shibden Hall, Halifax in the West Riding, Yorkshire: commission and inquisition of lunacy, into her state of mind and her property. 1843. The National Archives, C 221/28.

LGBT sources in a government archive

So often the lives of lesbian and bisexual women are difficult to trace. While women’s relationships with other women were never formally criminalised, neither were they socially acceptable. The lack of criminalisation has led to an absence of surviving records and evidence. Rarely are sources as explicit as the diaries of Anne Lister, but reading between the lines of common family history records (for example wills and the census) can reveal a lot.

The real question for me is, how unique was Anne Lister? While her coded diaries are exceptional in their survival and explicit nature, we can see from her sexual circle that she was far from alone as a lesbian in Halifax. How many ‘lost’ stories of lesbians like Anne are still waiting to be discovered?

Since April 2019, high quality digital images of every page of Anne’s diaries (SH:7/ML/E) have been available to view on the online catalogue of the West Yorkshire Archive Service.

To find out more about how to research the history of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender history at The National Archives, view our research guide on Sexuality and Gender Identity History.

This is a really interesting blog that illustrates very clearly how valuable The National Archives is as a resource.

Back in the 1980s I lived in Calderdale, (the lovely ‘Happy Valley’ and ‘Last Tango’ territory of Halifax). Having had a hint of the Lister diaries, and me being an educational history drama producer with YTV, I sought an ‘understanding’ with Helena Whitbread (first decoder of Anne Lister’s diaries). We agreed (as later did others) that we could try to explore the television potential of what Helena had discovered. I took it to the ‘non-educational’ tv commissioners and met, not exactly a stone-wall (to coin a phrase), but sufficient ill-ease about the themes for them not to pursue the opportunity. Now at last I can no longer feel too bad about my failure, and celebrate the success of Sally Wainwright’s potent dramatisation for these (I hope) more enlightened times. Sally has proved just the right playwright to seize the opportunity, and actors and crew have achieved an immaculate end result.

The first series was wonderful and showed Anne to be the most remarkable of women in the age she lived in and her enthusiasm for everything in her life came through in great detail. I think she was a great lady and really looked after her family , servants and tenants with true devotion.

What we in Hastings want to know is what happened here mentioned at the beginning of the series. When was Anne Lister here and who with? Where did she stay? What do the diaries say about her visit?

Anne

This collection of letters and diaries is extraordinary. I am watching the BBC Gentlemen Jack, based on a post mortem nickname for Anne Lister, probably because she was a middle class landowner whose dress and manner reflected her male world attitude, that is her determination as a business woman and coal mine owner and it’s excellent. Anne’s diaries show an openness of her sexuality, an openness which could criminalise her and her lover in the 1830s. Although the laws against homosexuality were mostly aimed at men and specific behaviour such as sodomy, lesbianism wasn’t generally accepted and women were occasionally prosecuted. The drama refers to two men being hung for homosexuality at a point when the characters are considering their commitment. Even though neither Anne Lister or Anne Walker had no shame about their relationship, they did have anxieties about it becoming public or the talk of it among their relatives, who gossipped. Anne Lister was in fact the subject of rumours generally. Anne Walker had several breakdowns because of the conflicts she felt about conformity with the wishes of family to marry and her awakening sexuality found in her love for Anne Lister.

Ultimately these diaries and other papers give us a unique insight into a hidden world of female sexual relations with each other and their almost obsessive feelings for one another. The couple made a commitment to each other, taking holy communion at the wedding of a friend and viewing that as a marriage ceremony. They eventually set out on long travels together, in Europe and Russia and beyond. Again this collection is extraordinary. Thank you.