Frost Fairs on the River Thames have long been part of popular imaginings of historical winters. The idea of the great river freezing over and of the people of London taking to the ice for a sort of great winter party has really caught the popular imagination – despite the fact that the Thames only froze over quite rarely, and the last big Frost Fair was held in the early 19th century (the demolition of old London Bridge in 1831 allowed the river to flow more quickly, making it less likely to freeze).

People take to the ice on the frozen River Thames at Twickenham in 1881 (COPY 1/52/538).

As the archive of central government, one might not expect records held at The National Archives to tell us much about these events but, as is so often the case, there are gems to be found in the collection. An exchange of letters between Sir Dudley Carleton and his friend John Chamberlain in the winter of 1607-8, preserved in the State Papers series, makes frequent reference to the hard weather. Carleton, who was in the countryside, asked Chamberlain, who was in London, ‘if it be true (as was told us this day) that the Thames is frozen over to make up the number of miracles of our own kings reigne, then let the world slide…’ [ref]SP 14/28 ff.217-19[/ref]

Chamberlain reported in January:

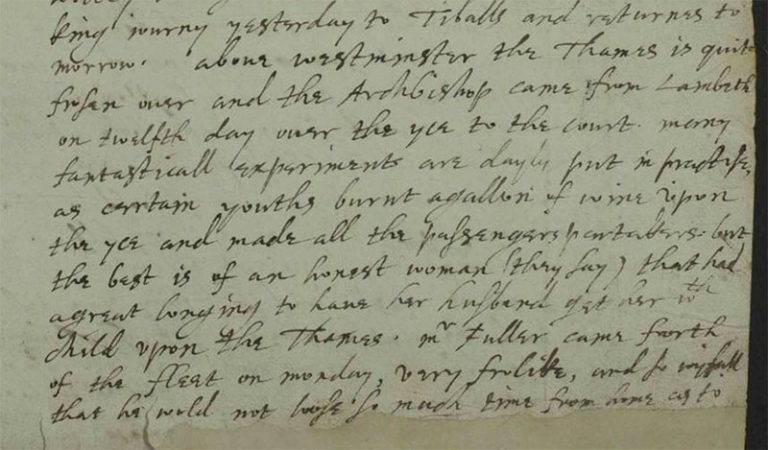

‘Above Westminster the Thames is quite frozen over and the Archbishop came from Lambeth on Twelfth Day over the ice to the court. Many fantasticall experiments are dayly put in practise as certain youths burnt a gallon of wine upon the ice and made all the passengers partakers. But the best is of an honest woman (they say) that had a great longing to have her husband get her with child upon the Thames.’[ref]SP 14/31 ff.59-60 [/ref]

Excerpt of letter from Chamberlain to Carleton, January 1608 (SP 14/31 f.59).

Towards the end of the 17th century was the coldest English winter on record, that of 1683-4. Again, the Thames froze over, and we can get a glimpse of the stir this caused in the letters from the Duke of York (later James II and VII) to his son-in-law William of Orange (later William III and II). On 4 January he wrote, ‘The weather is so very sharp and the frost so great that the river here is quite frozen over, so that for these three days last people have gone over it in severall places, and many booths are built upon it bettwene Lambeth and Westminster, where they can rest meat and sell drinke’.[ref]SP 8/3 ff.178-9[/ref]

A few days later he added, ‘The river here in the memory of man was never so long nor so much frozen as now, for they go over it in coaches and tis so smooth here before Whitehall and in severall other places of it that they go on it upon the scates, and tis now fiftenne days since twas quite frozen over’.[ref]SP 8/3 ff.180-1[/ref]

There followed a gap in their correspondence, and in his next letter the Duke explained that this was because the boats were frozen in and could not cross to Holland with mail – a glimpse that, for all the fun, the freezing temperatures also caused all sorts of problems.

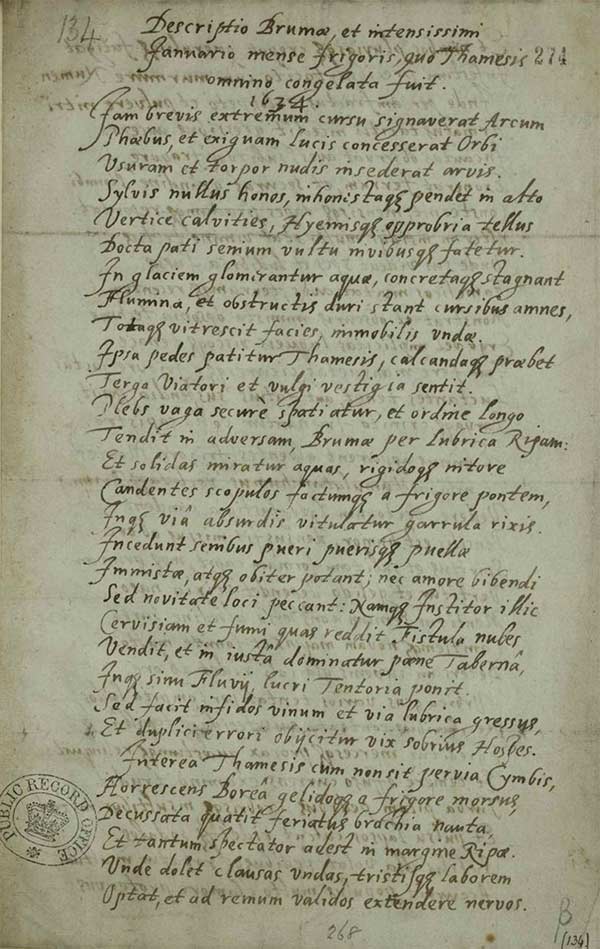

Records held here also reveal that people were prompted to express their feelings about the hard weather in more unexpected ways – for example, through the medium of poetry. In January 1635, the Thames froze, and our knowledge of the excitement this provoked is preserved in a remarkable poem, also in the State Papers series.[ref]SP 16/282 ff.274-5[/ref] This poem, written by a man called William Baker, is entirely in Latin. It is written in hexameter verse, echoing Latin authors of the classical period such as Virgil. Nowadays, the idea of writing a lengthy poem in Latin would be quite extraordinary, but in the early modern period secondary education was very much focused on Latin language and literature, so both the language itself and classical poetry would have been very familiar to educated people. Many of England’s most famous poets, such as John Milton, Andrew Marvell, and Thomas Campion, published Latin poetry, while Shakespeare drew heavily on classical literature and forms.

Excerpt of William Baker’s poem, January 1635 (SP 16/282 f.274).

But our poem is not by a towering genius of poetry – he is not a ‘known’ poet at all, and ‘William Baker’ is such a popular name that positively identifying him is very difficult. But the very fact of his obscurity is fascinating evidence of ordinary educated men in this period writing Latin poetry as a leisure activity.

According to Dr Victoria Moul of King’s College London, an expert in neo-Latin literature, this kind of poem – one written to mark an auspicious event – was very common in the 17th century: stylistically it is similar to other poems written at the time, with lots of alliteration and no rhyme.[ref] For a fascinating discussion of neo-Latin poetry in the early modern period, please see Victoria Moul ed., A Guide to Neo-Latin Literature (Cambridge, 2017).[/ref]

But what did our author actually write? Certainly, his verse confirms just how excited (indeed, over-excited) people got when the river froze. He wrote:

‘The wandering folk are safe as they wander, and in a long line they go back and forth along the solid ice, made slippery by Winter’s hard frost. And they are amazed by the solid water, the hard rocks glistening white, the bridge made from ice, and on the path, chattering, they celebrate with rough brawls… For the pedlar there supplies beer and things to smoke… But wine makes the going treacherous, the path is slippery, and the half-cut punter is sent flying by his double error.’[ref]This translation was provided by George Pounder, Head of Classics at Glenalmond College, with additional expertise from Dr Victoria Moul. I am tremendously grateful to both.[/ref]

Later on he recalled how everyone rushed out to play games, regardless of the work they were supposed to be doing:

‘The city folk play various games at the crossroads… cheekily they forget the benefits of earning a living… Elsewhere the happy crowd runs about on the treacherous ice, and they pack the snow into balls. So they can attack the enemy with these, they carry their playful weapons in their roguish arms; they hurl the snowballs at the faces of their friends.

‘Some build terrible monsters in the streets: they make beasts with their skilful hands, fashioning limbs out of packed snow and shaping them with their thumbs. Over here a cruel lion opens his jaws wide, while over there stands a wild bear, a pair of golden apples on its face for his two eyes, and sporting a collar of black coal: it fills the small boys with terror!’

The description of the snowball fight and of the snow bear – with his accessories made of fruit and coal – will be instantly familiar even to the 21st century reader. But, despite the fun, the author ends with a prayer for the coming of spring:

‘To the winter too may he grant an end and a limit – he from whose will everything depends, God himself.’

Used together, these records are thus interesting on a number of levels: as evidence of Latin literary culture in the 17th century, as evidence of what ordinary people really got up to during the legendary ‘Frost Fairs’, and as a charming reminder that our forebears centuries ago had very similar reactions to heavy snow and ice as we do today.