The Yemeni community forms a small but important part of Sheffield’s population, with most being families of the former steelworkers who migrated during the 1950s and 60s[ref]Estimates put the numbers at around 2,500. See for instance, Sheffield Libraries Archives and Information (2014). Sources for the Study of Sheffield’s Yemeni Community available at www.sheffield.gov.uk/home/libraries-archives/access-archives-local-studies-library/research-guides/yemeni-community (Accessed: 21/12/2020).[/ref].

Yemenis have made major contributions to the industrial development of Britain, both before and after the Second World War, yet for many remain, as Fred Halliday described in his pioneering study Arabs in Exile, an ‘invisible community’, often absorbed into broader group identities such as lascar, Muslim, Arab, Asian, and more[ref]Halliday, Fred (1992) Arabs in Exile: Yemeni Migrants in Urban Britain, London: I B Tauris, p. 59 & 141.[/ref].

This blog combines National Archives (TNA) sources with oral history interviews to develop an insight into the journeys of Yemeni former steelworkers, who travelled to Sheffield after the Second World War.

Background

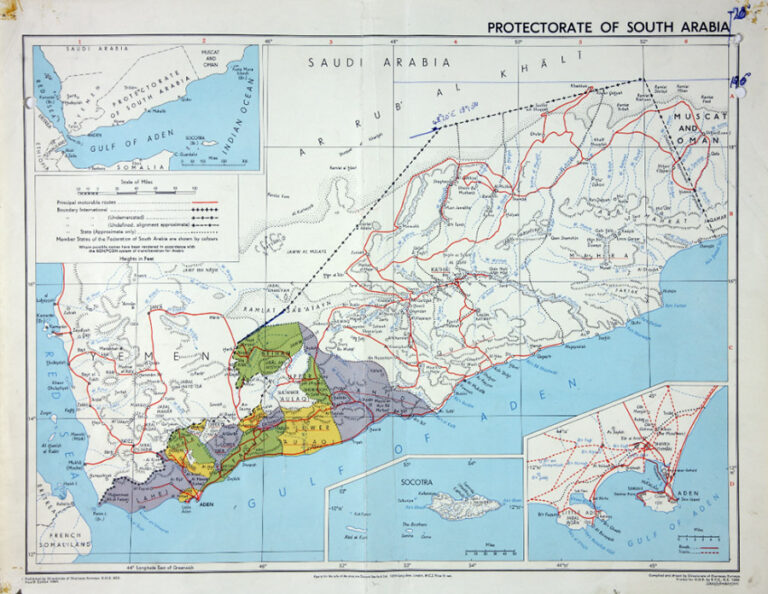

The majority of Sheffield’s Yemenis came from the Aden Protectorate, particularly the provinces of Yafai, Shaibi, Hadida and Dhala, as well as North Yemen, particularly Rada, Gubin and Shar, some of which can be seen on the following Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) map[ref]For more information, see: Searle, Chris and Shaif, Abdulgalil (1991) ‘Drinking from one pot: Yemeni unity, at home and overseas’, Race and Class 32(4), pp. 65-81.[/ref].

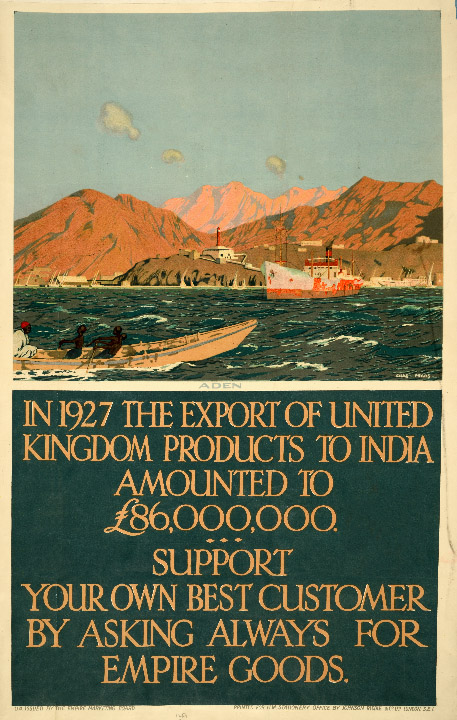

The British founded a coaling station in Aden in 1839 and began to bring South Yemen under their sphere of influence in the 1870s. The function of Aden was characteristic of that of strategic colonies during the imperial era: it wasn’t exploited so much for its mineral wealth, but for its location on the short-sea route to India, as well as further East[ref]Towards a concise summary, Sicherman (1972: 33) asks the question: ‘Why did the British keep Aden? For two reasons: the place proved commercially convenient and militarily useful. On the first was built Aden’s enormous bunkering trade, behind only New York and London in tonnage. On the second was built a coastal fortress watching West to guard East, monitoring Suez to guard India’, cf. Sicherman, Harvey (1972) Aden and British Strategy, 1839-1968 Philadelphia: Foreign Policy Research Institute. See also; Halliday, Fred (1974) Arabia Without Sultans, Middlesex: Penguin Books, pp.153-177.[/ref].

The importance of the port in facilitating trade with India – providing a staging post for steamships, not to mention cheap labour from the hinterland to feed their furnaces with coal – is certainly apparent in this poster (right) used by the Empire Marketing Board, and featuring Aden as its backdrop.

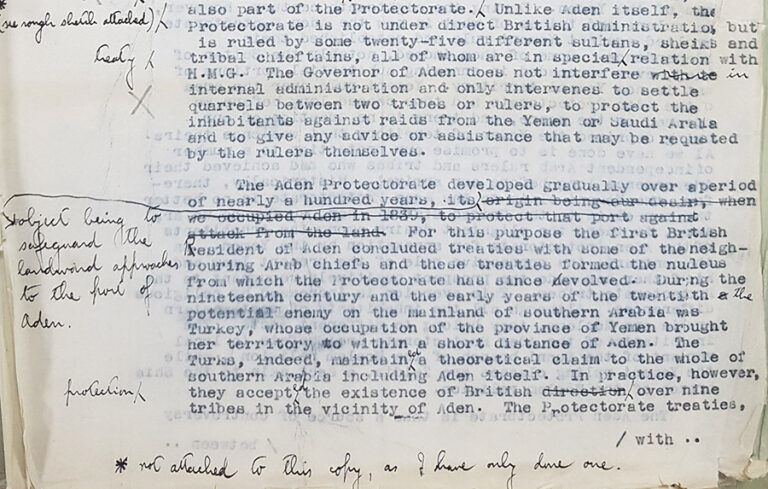

The handwritten note on this Colonial Office document below, summarises the reasons that the British kept the broader protectorate, its ‘object being to safeguard the landward approaches to the port of Aden’.

Halliday (1974: 164) explains further, ‘The boom in Aden had only a limited effect on the tribal areas, due to the fact that the Aden growth was generated externally and its profits went abroad’. This ‘reflected a political decision by the British to keep the tribal areas as unchanged as possible. … If the economic changes had affected the hinterland’s structure, the political stability and the buffer zone that Britain wanted among the tribes might have been undermined’.

The insulation of the Yemeni hinterland from the growth in Aden provided the major ‘push’ factor of migration, while the post-war boom in Britain (as well as chain migration – where prior migrants facilitate the journeys of successive sojourners/settlers) provided the major ‘pull’ factor.

The journey to Britain

While the official documents at The National Archives are important in piecing together an understanding of the Yemeni background, and the broader context of migration, they tell us little about the rich and varied lived experiences of the migrants themselves. These include the journeys to Britain, which often feature prominently in the life-stories of Yemeni elders. This emphasises the need for mixed methods research, and historians to engage with communities themselves. The remainder of this blog will foreground these stories.

Many of the Yemenis made indirect journeys to Britain on French ships – stopping in the French colony of Djibouti, and then changing in France to continue their onwards journey to Britain – and as a result would not appear on UK passenger lists, as they fail to record travel within Europe[ref]For more information, see The National Archives’ research guide to Passengers.[/ref]. Nasser is one migrant who recalls a stop in Djibouti:

When I first came to England from Yemen in 1959, I travelled on a ship from the port of Djibouti. We had very little money, so we bought tickets to sleep down in the lowest part of the ship. We could see the sea just below us when we looked out of the portholes.

Perhaps being so low down in the ship made me feel bad, because I became sea sick, I went on the deck to breathe some fresh air and an English lady saw me. She noticed that I was sick and invited me to her cabin on the upper deck to give me a tablet or an aspirin for my headache. Her cabin was very clean and luxurious, and it had soft and beautiful furniture – very different from down below in the ship where we slept.

While she was talking to me and giving me the aspirin, the captain walked into her cabin. He was very angry when he saw me there and he told me to go back down below. He said that I had no business in that part of the ship. He was not interested in what the lady said and didn’t listen to her. …

The Yemeni passengers travelled in steerage class below deck and the differences in the conditions of their holds and the cabins of the largely white first-class passengers, was certainly very marked.

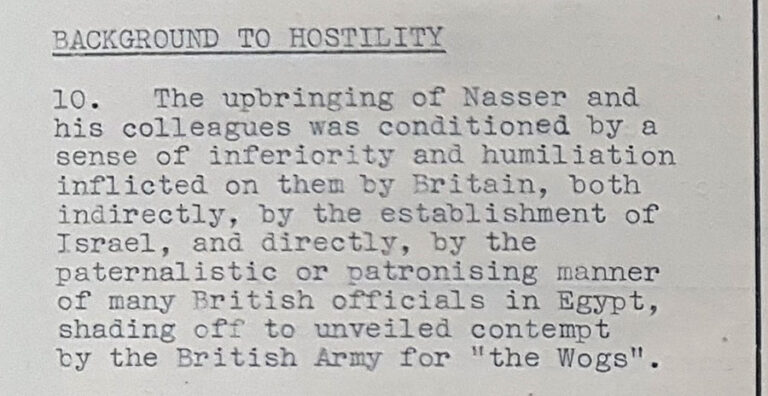

The majority of the migrants travelled from Aden, through the short sea route, via Suez. Those that travelled around the time of the Suez War in 1956 when anti-Arab racism was at an apex had to endure a particularly hostile and difficult journey. The following FCO document, from a file entitled, ‘Propaganda attitude towards Nasser and the UAR’ emphasises very strongly that, far from being an aberrant lapse from broadly held liberal traditions, racism was an integral component of imperial expansion, and the wars waged to support it[ref]As Sivanandan described it: ‘racism is not its own justification. It is necessary only for the purpose of exploitation: you discriminate in order to exploit or, which is the same thing, you exploit by discriminating.’ Sivanandan A. (1991) A Different Hunger: Writings on Black Resistance, London: Pluto Press. P113.[/ref]:

While far from the analysis of the psychological effects of colonialism presented by authors such as Frantz Fanon[ref]Fanon, Frantz (1986) Black Skins, White Masks, London: Pluto Press.[/ref], the FCO file does however acknowledge the depth of racism within the British state and the agencies tasked with enforcing its imperial ambitions. Its entrenched nature among both the officials concerned with the exercise of ‘soft power,’ as well as the troops, representing what Louis Althusser (1971: 132) described as ‘the Repressive State Apparatus [which] functions “by violence”’, is jarring[ref]Althusser, Louis (1971) Lenin and Philosophy and Other Essays, New York: Monthly Review Press.[/ref]. The document is especially valuable too, as it’s clearly slipped through the FCO’s programme to destroy and disappear files seen to ‘embarrass HMG [Her Majesty’s Government] … members of the police, military forces or public servants…’[ref]See, for instance, Cobain, Ian (2016: 123) History Thieves: Secrets, Lies and the Shaping of a Modern Nation, London: Portobello Books.[/ref]. A point which again highlights the importance of engaging with community voices, such as Abdullah’s, who travelled in 1956:

We travelled on a French ship and the crew treated us very badly. The captain and officers said that we Arabs must stay below deck, and not come on the deck and mix with the first class passengers who were enjoying themselves in the sun … and having plenty to drink.

It was 1956 and just before the war over the Suez Canal. The Egyptian immigration officers supported us and told the French crew to treat us better. But we were angry at them and decided to make a protest. So just before the ship arrived at Marseilles we started to throw a lot of the ship’s furniture and bed sheets into the Mediterranean Sea.

Abdullah’s story highlights powerfully an early example of the interwoven oppressions of racism and class discrimination, as well as the struggles waged against them, which would thread throughout the lives of the Yemenis in Sheffield, as they came to labour in many of the least desirable jobs in industry often rejected by the indigenous working class.

Against this backdrop of what Cedric Robinson might describe as ‘racial capitalism’ – a term which draws attention to the ways in which racism ‘permeate[s] the social structures emergent from capitalism’[ref]Robinson, Cedric (2000: 2) Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition, Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.[/ref] – some migrants were nonetheless fortunate enough to be in receipt of many individual acts of kindness from locals. This was certainly the case in Ali’s story, who is particularly grateful to his taxi driver and Doreen, who took him in:

When I arrived at Sheffield Station from London after I left the ship at Tilbury, I didn’t know anyone and I didn’t know where to go. The Taxi driver said, ‘Try Attercliffe, I think there are some Arabs there’, but I didn’t understand him because he didn’t speak Arabic and I didn’t speak English. He took me to Attercliffe, and after to Darnall Road. He started to knock on the doors of the houses to ask the people who lived there if there was a room to rent.

On the eleventh house where he knocked, a lady called Doreen opened the door. ‘He can stay with me, he’s welcome’, she said when she saw me. So I moved into that house. It was near Brown Bailey’s, the steel factory. So later at night I went there to ask for a job. I got a job there in the middle of the night. When I came back to Doreen’s house she was angry and worried about me, she gave me a slap. ‘Where did you go all night?’ she shouted. I answered in Arabic, ‘I found a job’, and I was very happy. But no one understood my language.

The National Archives’ records and the stories quoted only begin to hint at the richness of the narratives of Yemeni former steelworkers in Sheffield. Although, as Halliday observed, often an ‘invisible community,’ their contributions to industry and society in Britain’s industrial heartlands (as well as in its coastal communities before), have been crucial in both the pre- and post-war periods[ref]For more information, see: Halliday (1992); Searle and Shaif (1991); Searle, Kevin (2010) From Farms to Foundries: An Arab Community in Industrial Britain, Oxford: Peter Lang. For coastal communities, see Lawless, Richard (1995) From Ta’izz to Tyneside: Arab Community in the North-east of England in the Early Twentieth Century, Exeter: University of Exeter Press.[/ref].